Working at McDonald’s got me to college, for which I thank the world’s largest restaurant chain. I worked there for three years, beginning at about $1 an hour, during the middle of the 20th century. Back then, a buck bought something. I consumed tons of hamburgers and fries and gallons of milkshakes for free — unconscious consumption.

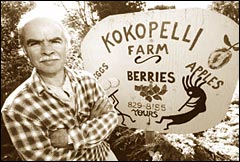

Bliss on the farm.

Photo: metroactive.com

I have not thought much about McDonald’s in the 40 years since I worked there, during which time I have never eaten there again. But McDonald’s and restaurants of its ilk are in the news with this week’s release of the film Fast Food Nation, based on the best-selling nonfiction book by Eric Schlosser. Directed by Richard Linklater, the film takes on a slice of culture that’s familiar to many, but fully known to few.

What do you think the main ingredients of a hamburger are? Beef is the most visible, but oil is essential to modern factory farming, which is what supplies fast food. I still recall the “End of Cheap Oil” article in National Geographic two years ago, which featured a full-page photo of a cow with the following caption: “The price of steak: a pound of beef takes three-quarters of a gallon of oil to produce.”

Ruining your health and the health of the planet, all in one convenient bite.

But it is too easy to blame McDonald’s, Exxon, and other corporations for the damage they do. Sure, they mold our consumption patterns and financially benefit from them. But we need to take individual responsibility. If enough of us demand healthier food, and are willing to pay for it, we could get it.

Schlosser wrote another book, Chew on This, designed to show teenagers the truth about their food choices. The food industry wasted no time viciously attacking it. In an interview in May, Schlosser marveled to Forbes that “the industries they represent make over $300 billion a year in revenues, and they’ve gone to the expense and trouble to attack my book. I don’t even have my own website.”

When asked by Forbes, “Aren’t fast-food chains just supplying what American appetites demand?” Schlosser responded, “The American people were not demanding chicken nuggets. The industry has done a lot to create that demand.” McDonald’s, it seems, spends more money on advertising than any other brand in the world.

In another recent book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Michael Pollan follows a McDonald’s meal back to its source: corn in an Iowa field. He goes on to count 13 ways that corn is present in a typical McDonald’s meal. Sounds harmless enough, but once milled, refined, and recompounded, corn can become a number of things, including high-fructose corn syrup, which can lead to diabetes and worsen a number of other health threats.

So what’s the alternative?

While I was busy flipping burgers, my Uncle Dale and Auntie Elva were tending a small, diversified family farm in Iowa. I helped them as a pre-teen — the happiest years of my youth. I got to drive a tractor (even after I ran into the chicken coop), stack hay, gather warm eggs, fish, play with barnyard animals, have rotten-egg fights, and hear stories at night during a time before we had electricity. I was learning, though I didn’t know it then, that small-scale family farms can provide more than good food to the families who live there and the small towns that grow up around them.

I eventually faced the choice of continuing on the college and city path that McDonald’s had helped pave for me, or following the example of my uncle and aunt. I followed the college path, and it took me nearly 25 years to return to farm and country living, with its bumpy, sometimes unpaved roads. In 1991, I moved to an abandoned farm on less than two acres in Sonoma County, Calif. I worked it almost daily for a dozen years. Kokopelli Farm is plant-based, though I keep chickens for their eggs, manure, beauty, and companionship.

Every year I place tons of newspapers, burlap coffee bags, and cardboard boxes around my plants to limit weed growth and promote helpful activity in the soil. Instead of a neighbor’s cow manure polluting a nearby stream, it ends up composting on my farm and fertilizing my organic berries, apples, mushrooms, and other produce.

I broke my connection to McDonald’s when I realized how hazardous it was. Years later, I restored my connection to the healthier small-scale family-farm legacy within which I was raised. It was a choice that has enhanced my life. Most of us can make healthier eating, living, and consuming choices, even if a family farm is not in our legacy — we just need to listen to our gut.