Generations from now, people might react to the idea of piping gas into houses the same way we now think of burning coal in the fireplace for heat: as a relic of a less-advanced and soot-filled time.

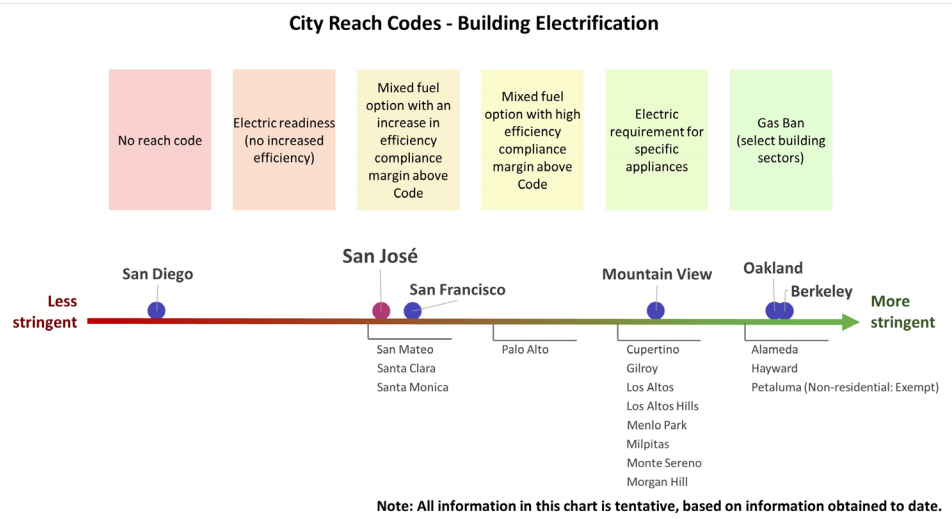

The turning point came earlier this year, when Berkeley, California, became the first city in the country to ban natural-gas in newly constructed buildings in July. Within a few weeks, four other cities in California passed their own rules to encourage buildings to use only electricity, which means no gas for heating or cooking. Two more cities, Menlo Park and Santa Monica, followed suit last week. At least 50 California cities — including the biggies: Los Angeles, San Jose, San Francisco, and Sacramento — are considering similar plans. And the trend has crept out of California, with Seattle and Brookline, Massachusetts mulling their own proposals.

“This is a very exciting year: It’s kind of a tipping point,” said Stet Sanborn a principle at SmithGroup, an architecture and engineering firm. Local governments were primed to follow Berkeley’s lead because they’ve made carbon-cutting pledges.

“They all have signed pacts and passed resolutions,” Sanborn said, “and now that movement is starting to happen, no one wants to be left behind.”

For developers, too, gas just doesn’t make sense for California buildings anymore, Sanborn said. It’s now less expensive and more convenient to do without it. “All of the all-electric buildings I’ve done have been at cost or lower [than those with gas] because you’re not paying for gas lines to be connected and run all through the building,” he said.

California Energy Commission

No surprise that the gas industry sees things differently, warning that forcing everyone to go electric could increase costs and, perversely, worsen pollution. “Pursuing clean energy should include looking for ways to reduce energy consumption, utilizing the current energy infrastructure in the most efficient way,” wrote the American Public Gas Association.

Cities have been turning to Sanborn and other engineers for advice in crafting the new rules so that they don’t pass something that backfires. It’s not better, from a carbon-cutting perspective, to trade gas for electricity if that electricity comes from a coal plant, Sanborn said. That’s because heating a home with gas is cleaner than burning gas and coal to produce electricity, then converting that electricity back into heat once it reaches your house.

California gets a little more than half of its electricity from low-carbon sources — wind turbines, solar panels, dams, and one nuclear power plant — which makes electric heating a smarter choice, even before considering new evidence that aging networks of city pipes are leaking much more greenhouse gas than previously suspected, Sanborn said.

The Berkeley ban outlaws gas in new single family homes starting in January. It will apply to the construction of larger buildings as soon as state regulators put the finishing touches on standards for all-electric buildings. Most of the other cities that have passed ordinances are taking a more moderate approach. Builders in those cities will be able to connect to gas pipelines only if they compensate by making their buildings more energy efficient — by improving insulation, for instance, and using more efficient lighting. That increases costs and provides a nudge to get builders and architects used to doing things the old way a reason to look at the electric alternative.

City of San Jose

Decisions made in 2019 could determine whether people default to clean or polluting energy when they switch on heaters for the next century, according to the California Energy Commission, which writes the state’s energy efficiency standards for buildings.

Nearly all of the gas people use in their homes goes to furnaces and water heaters. Cooking only accounts for 2 percent of gas use, but when people talk about gas bans they tend to focus on their stoves. And lots of people insist that no cooktop can be better than gas.

Sanborn’s father used to be one of those people. A few years ago, Sanborn helped his parents fix up a cabin in northern Minnesota. “My dad said, ‘I want gas! I’ve always cooked on gas,’” Sanborn remembers. But he convinced his parents that the cost and danger of trucking propane into the woods made it worthwhile to at least try an induction stove (which uses electro-magnetism to vibrate the atoms in cookware, creating heat). His skeptical father loved the induction stove once he’d tried it. “It’s faster, it’s easier, and it’s safer,” Sanborn said. “You can put your hand on the cooktop while you are boiling water and you won’t get burned.”

The wave of cities moving away from gas is likely the start of something bigger, said Matt Gough, a senior campaign representative for the Sierra Club, in a statement. “These cities all have at least one thing in common: they are sending a clear signal that gas is in the past and building electrification is the cost effective, climate-smart solution for the health and well-being of communities now and in the future.”