The one-year anniversary of the death of environmental legend David Brower has come and gone, just a week after the U.S. Department of Justice decided not to appeal a dolphin protection lawsuit the Earth Island Institute filed with Dave back in 1999.

Dolphins on the run.

Photo: NOAA.

For reasons that are still unknown, a small portion of the world’s tuna swim with dolphins in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. Ever since the late 1950s introduction of mile-long purse seine nets, fishing fleets have deliberately chased and netted dolphins in order to catch the tuna swimming beneath, resulting in the death of an estimated seven million dolphins over the past four decades.

In 1990, after several years of tuna boycotts and save-the-dolphins demonstrations, Earth Island Institute reached an agreement with U.S. tuna processing companies stating that all tuna caught and sold would henceforth be “dolphin-safe.” The dolphin-safe label on tuna cans in the United States and Europe means no dolphins were chased or netted during catch operations, nor were any killed or injured.

A purse seine net reels in the catch.

Photo: NOAA.

But five years later, former President Clinton and former Vice President Al Gore, in their heady promotion of “free trade,” promised Mexico’s government (at the behest of a handful of Mexican tuna millionaires) that the restrictions on Mexican tuna imports would be dropped. (The majority of Mexico’s tuna fleet continues to chase, net, and kill dolphins.)

The Clinton administration proposed weakening the standards for the dolphin-safe label to an absurd degree: If an observer aboard the fishing vessel didn’t see any dolphins die outright, then the tuna could be considered “dolphin-safe.” Sort of like claiming that Russian Roulette is safe for children, as long as a bullet doesn’t happen to be in the firing chamber.

After a tough legislative fight, Congress decided in 1997 that the administration should base tuna label standards on science, not trade politics. However, despite studies by government scientists showing that dolphin populations were still being depleted in fishing areas, Clinton’s commerce secretary, William Daley, decided that the research did not absolutely “prove” that fishing was the cause of the continued lack of recovery for dolphins. And so he administratively weakened the dolphin-safe label standards, which was what Mexico’s ruthless tuna millionaires wanted in the first place. Earth Island sued.

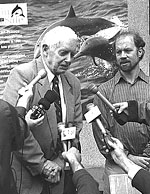

David Brower meets the press.

Photo: Mark J. Palmer.

David Brower, then chair of Earth Island, was our lead plaintiff. Although he was 86-years-old, Dave came to a press conference in front of the San Francisco federal courthouse when we filed the case, “David R. Brower v. William Daley.” Dave told me that he had only met a dolphin once in his life. It was a wild dolphin in Florida that came up to the boat docks to get fish from the locals. Dave spent some time tossing a ball to the dolphin, and the dolphin spent some time tossing it back to Dave. Dave said he was never sure whether he or the dolphin was in charge of the game.

In March 2000, federal Judge Thelton Henderson, who has heard several previous Earth Island dolphin cases, agreed with our lawyers and issued an opinion preventing the weakening of the dolphin-safe tuna label.

The Clinton administration met behind closed doors with the Mexican tuna industry and the Mexican government. (Earth Island and our allies were refused attendance.) They agreed to appeal “Brower v. Daley” to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Dave Brower passed away about six weeks before the arguments were heard on appeal before a three-judge panel. In July 2001, the appeals court issued its decision: All three judges agreed with Earth Island and Judge Henderson. The government’s proposal to weaken the dolphin-safe label standards was, in their words, “arbitrary and capricious.” Since the government has decided not to appeal to the Supreme Court, “Brower v. Daley” (now known as “Brower v. Evans”) will stand as law, a potent precedent that free trade cannot come at the expense of wildlife.

So I suppose a new maxim is in order for Dave and the dolphins: Old environmentalists may die, but they never lose their appeal.