In this post, I will summarize what the recent scientific literature says are the key impacts we face in the second half of the century if we stay anywhere near our current emissions path. I will focus primarily on:

- Staggeringly high temperature rise, especially over land — some 10°F over much of the United States

- Sea level rise of 3 to 7 feet, rising some 6 to 12 inches (or more) each decade thereafter

- Dust Bowls over the U.S. SW and many other heavily populated regions around the globe

- Massive species loss on land and sea — 50% or more of all life

- Unexpected impacts — the fearsome “unknown unknowns”

- More severe hurricanes — especially in the Gulf

Equally tragic, a 2009 NOAA-led study found the worst impacts would be “largely irreversible for 1000 years.”

The single biggest failure of messaging by climate scientists (until very recently) has been the failure to explain to the public, opinion makers, and the media that business-as-usual warming results in impacts that are beyond catastrophic. For these impacts, terms like “global warming” and “climate change” are essentially euphemisms. That is why I prefer the term “Hell and High Water.”

Business-as-usual typically means continuing at recent growth rates of carbon dioxide emissions, which we now know would take us to atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide greater than 1000 ppm (see U.S. media largely ignores latest warning from climate scientists: “Recent observations confirm … the worst-case IPCC scenario trajectories (or even worse) are being realised” — 1000 ppm). We are at about 8.5 billion metric tons of carbon a year (GtC/yr) and, until the recent global economic recession, were rising about 3% per year.

What is less well understood is that even a very strong mitigation effort that kept carbon emissions this century to 11 GtC a year on average would still probably take us to 1000 ppm — a little noted conclusion of the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report (see “Nature publishes my climate analysis and solution“).

The scientific community has spent little time modeling the impacts of a tripling (~830 ppm) or quadrupling (~1100 ppm) carbon dioxide concentrations from preindustrial levels. In part, I think, that’s because they never believed humanity would be so stupid as to ignore the warnings and simply continue on its self-destructive path. In part, they lowballed the difficult-to-model amplifying feedbacks in the carbon cycle.

So I pieced together those impacts from available studies and from discussions with leading climate scientists for my book, Hell and High Water. But now as climate scientists have sobered up to their painful role as modern-day Cassandra’s, the scientific literature on what we face is much richer. Let me review it here.

TEMPERATURE

Two of the best recent analyses of what we are headed towards can be found here:

- M.I.T. joins climate realists, doubles its projection of global warming by 2100 to 5.1°C

- Hadley Center: “Catastrophic” 5-7°C warming by 2100 on current emissions path

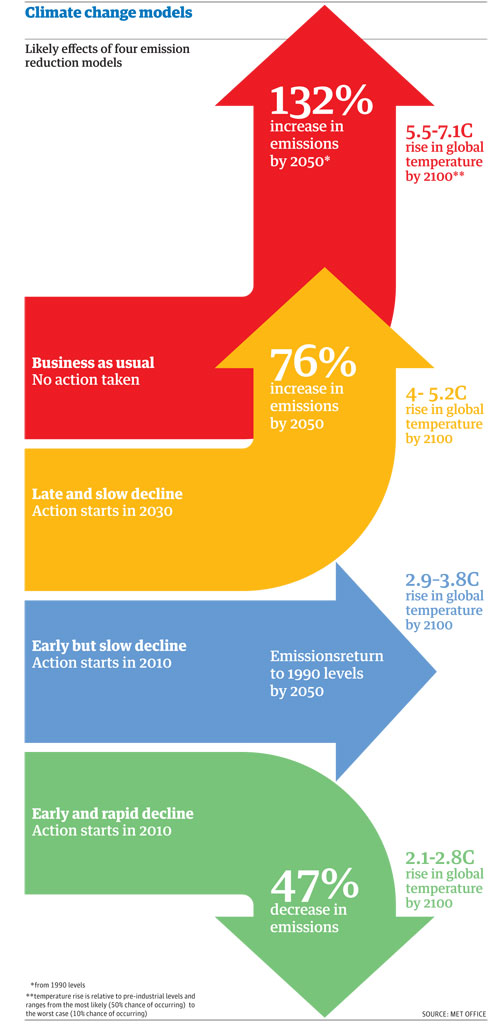

As Dr. Vicky Pope, Head of Climate Change Advice for the Met Office’s Hadley Centre explains on their website (here):

Contrast that with a world where no action is taken to curb global warming. Then,temperatures are likely to rise by 5.5 °C and could rise as high as 7 °C above pre-industrial values by the end of the century.

That likely rise corresponds to roughly 9°F globally and typically 40% higher than that over inland mid-latitudes (i.e. much of this country) — or well over 10°F.

[Note: The MIT rise is compared to 1980-1999 levels see study here). So you can add at least 0.5 C and 1.0°F for comparison with pre-industrial temperatures.]

Based on two studies in the last few years:

By century’s end, extreme temperatures of up to 122°F would threaten most of the central, southern, and western U.S. Even worse, Houston and Washington, DC could experience temperatures exceeding 98°F for some 60 days a year. Much of Arizona would be subjected to temperatures of 105°F or more for 98 days out of the year–14 full weeks.

Yet that conclusion is based on studies of only 700 ppm and 850 ppm, so it could get much hotter than that.

And the Hadley Center adds, “By the 2090s close to one-fifth of the world’s population will be exposed to ozone levels well above the World Health Organization recommended safe-health level.”

The Hadley Center has a huge but useful figure which I will reproduce here:

SEA LEVEL RISE

A 5.5°C warming would likely lead to the mid- to high-range of currently projected sea level rise — 5 feet or more by 2100, followed by 10 to 20 inches a decade for centuries. The best recent study is

Needless to say, a sea level rise of one meter by 2100 would be an unmitigated catastrophe for the planet, even if sea levels didn’t keep rising several inches a decade for centuries, which they inevitably would. The first meter of SLR would flood 17% of Bangladesh, displacing tens of millions of people, and reducing its rice-farming land by 50 percent. Globally, it would create more than 100 million environmental refugees and inundate over 13,000 square miles of this country. Southern Louisiana and South Florida would inevitably be abandoned. And salt water infiltration will only compound this impact (see “Rising sea salinates India’s Ganges“). As will hurricanes (see below).

The scientific literature has been moving in this direction for a couple of years now — too late for the IPCC to consider in its latest assessment. For instance, an important Science article from 2007 used empirical data from last century to project that sea levels could be up to 5 feet higher in 2100 and rising 6 inches a decade (see Inundated with Information on Sea Level Rise)!

Another 2007 study from Nature Geoscience came to the same conclusion (see “Sea levels may rise 5 feet by 2100“). Leading experts in the field have a similar view (see “Amazing AP article on sea level rise” and “Report from AGU meeting: One meter sea level rise by 2100 “very likely” even if warming stops?“).

Note: Since global warming deniers and delayers like to hide behind the IPCC’s 2007 sea level estimate — even though they really don’t believe most of what the IPCC says or most of the scientific literature on which it bases its conclusion — you’re going to be hearing the IPCC estimate for another several years, until the IPCC does a new report and puts in a more realistic estimate. That said, while the delayers never acknowledge it, even the 2007 IPCC report “was the first to acknowledge that the melting of the Greenland ice sheet from rising temperature [which would raise the oceans 23 feet] could result in sea-level rise over centuries rather than millennia,” as the NYT put it (see “Absolute MUST Read IPCC Report: Debate over, further delay fatal, action not costly“).

Yet even a major report signed off on by the Bush administration itself was forced to concede that the IPCC numbers are simply too out of date to be quoted anymore:

DUST-BOWL-IFICATION

Then we have moderate drought over half the planet, plus the loss of all inland glaciers that provide water to a billion people.

“The unexpectedly rapid expansion of the tropical belt constitutes yet another signal that climate change is occurring sooner than expected,” noted one climate researcher in December 2007. A 2008 study led by NOAA noted, “A poleward expansion of the tropics is likely to bring even drier conditions to” the U.S. Southwest, Mexico, Australia and parts of Africa and South America.”

In 2007, Science (subs. req’d) published research that “predicted a permanent drought by 2050 throughout the Southwest” — levels of aridity comparable to the 1930s Dust Bowl would stretch from Kansas to California. And they were only looking at a 720 ppm case! The Dust Bowl was a sustained decrease in soil moisture of about 15% (”which is calculated by subtracting evaporation from precipitation”).

A NOAA-led study similary found permanent Dust Bowls in Southwest and around the globe on our current emissions trajectory (and irreversibly so for 1000 years). And as I have discussed, future droughts will be fundamentally different from all previous droughts that humanity has experienced because they will be very hot weather droughts (see Must-have PPT: The “global-change-type drought” and the future of extreme weather).

I should note that even the “moderate drought over half the planet″ scenario from the Hadley Center is only based on 850 ppm (in 2100). Princeton has done an analysis on “Century-scale change in water availability: CO2-quadrupling experiment,” which is to say 1100 ppm. The grim result: Most of the South and Southwest ultimately sees a 20% to 50% (!) decline in soil moisture.

SPECIES LOSS ON LAND AND SEA

In 2007, the IPCC warned that as global average temperature increase exceeds about 3.5°C [relative to 1980 to 1999], model projections suggest significant extinctions (40-70% of species assessed) around the globe. That is a temperature rise over pre-industrial levels of a bit more than 4.0°C. So a 5.5°C rise would likely put extinctions beyond the high end of that range.

And, of course, “When CO2 levels in the atmosphere reach about 500 parts per million, you put calcification out of business in the oceans.” There aren’t many studies of what happens to the oceans as we get toward 800 to 1000 ppm, but it appears likely that much of the world’s oceans, especially in the southern hemisphere, become inhospitable to many forms of marine life. A 2005 Nature study concluded these “detrimental” conditions “could develop within decades, not centuries as suggested previously.”

A 2009 study in Nature Geoscience warned that global warming may create “dead zones” in the ocean that would be devoid of fish and seafood and endure for up to two millennia (see Ocean dead zones to expand, “remain for thousands of years”).

UNEXPECTED IMPACTS

If we go to 800 ppm — let alone 1000 ppm or higher — we are far outside the bounds of simple linear projection. Some of the worst impacts may not be obvious — and there may be unexpected negative synergies. The best evidence that will happen is the fact that it is already happened with even a small amount of warming we have seen to date.

“The pine beetle infestation is the first major climate change crisis in Canada” notes Doug McArthur, a professor at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. The pests are “projected to kill 80 per cent of merchantable and susceptible lodgepole pine” in parts of British Columbia within 10 years — and that’s why the harvest levels in the region have been “increased significantly.”

As quantified in the journal Nature, “Mountain pine beetle and forest carbon feedback to climate change,” (subs. req’d), which just looks at the current and future impact from the beetle’s warming-driven devastation in British Columbia:

… the cumulative impact of the beetle outbreak in the affected region during 2000–2020 will be 270 megatonnes (Mt) carbon (or 36 g carbon m-2 yr-1 on average over 374,000 km2 of forest). This impact converted the forest from a small net carbon sink to a large net carbon source.

No wonder the carbon sinks are saturating faster than we thought (see here) — unmodeled impacts of climate change are destroying them:

Insect outbreaks such as this represent an important mechanism by which climate change may undermine the ability of northern forests to take up and store atmospheric carbon, and such impacts should be accounted for in large-scale modelling analyses.

And the bark beetle is slamming the Western U.S. and Alaska, too (see “Oldest Utah newspaper: Bark-beetle driven wildfires are a vicious climate cycle“).

The key point is this catastrophic climate change impact and its carbon-cycle feedback were not foreseen even a decade ago — which suggests future climate impacts will bring other equally unpleasant surprises, especially as we continue on our path of no resistance.

HURRICANES

Even if we don’t see an increase in the worst hurricanes hurricanes, the rising sea levels alone would put a growing number of coastal cities below sea level. Such cities are particularly hard to protect from major hurricanes as we saw with New Orleans. And that suggests in the second half of this century, we will be increasingly reluctant to rebuild cities devastated by major hurricanes.

That said, the literature suggests we will see an increase in severe hurricanes (see “ Hurricanes ARE getting fiercer — and it’s going to get much worse“). A 2008 Nature studied concluded:

The team calculates that a 1 ºC increase in sea-surface temperatures would result in a 31% increase in the global frequency of category 4 and 5 storms per year: from 13 of those storms to 17. Since 1970, the tropical oceans have warmed on average by around 0.5 ºC. Computer models suggest they may warm by a further 2 ºC by 2100.

Well, actually, those are the old computer models running old scenarios of emissions without much consideration of amplifying carbon cycle feedbacks. On our current emissions path, key parts of the tropical oceans are likely to warm considerably more than 2°C by century’s end.

For a longer discussion of why future hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico are likely to become far more dangerous in the future, see (Why global warming means killer storms worse than Katrina and Gustav, Part 1 and Part 2).

CONCLUSION

We can’t let this happen. We must pay any price or bear any burden to stop it.

And let me make one final point. I think it is increasinly clear the “middle ground” scenarios are unstable in that once you hit 500 ppm (or possibly lower), the amplifying feedbacks kick in: These feedbacks include:

- The defrosting of the permafrost

- The drying of the Northern peatlands (bogs, moors, and mires).

- The destruction of the tropical wetlands

- Decelerating growth in tropical forest trees — thanks to accelerating carbon dioxide

- Wildfires and Climate-Driven forest destruction by pests

- The desertification-global warming feedback

- The saturation of the ocean carbon sink

As Dr. Pope puts it, “If the climate turns out to be particularly sensitive to increases in greenhou

se gases and the Earth’s biological systems cannot absorb very much carbon then temperature rises could be even higher.”

Indeed, some of the best research on this has come from the Hadley Center, since it has one of the few models that incorporates many of the major carbon cycle feedbacks. In a 2003Geophysical Research Letters (subs. req’d) paper, “Strong carbon cycle feedbacks in a climate model with interactive CO2 and sulphate aerosols,” the Hadley Center, the U.K.’s official center for climate change research, finds that the world would hit 1000 ppm in 2100 even in a scenario that, absent those feedbacks, we would only have hit 700 ppm in 2100. I would note that the Hadley Center, though more inclusive of carbon cycle feedbacks than most other models, still does not model most of the feedbacks above or any feedbacks from the melting of the tundra even though it is probably the most serious of those amplifying feedbacks.

So we must stabilize at 450 ppm or below — or risk what can only be called humanity’s self-destruction. Since the cost is maybe 0.11% of GDP per year — or probably a bit higher than that if we shoot for 350 ppm — the choice would seem clear. Now if only the scientific community and environmentalists and progressives could start articulating this reality cogently.