Vinni Orsini used to work in a place straight out of a fantasy: From the vast windows of his classroom, the social studies teacher and his students could look in one direction and see white sand beaches and the clear waters of the Pacific Ocean. In the other direction rose Mt. Tapochau, its peak the highest point on the island of Saipan.

“Man, my classroom was beautiful,” Orsini said. The inside was decorated with his students’ artwork, including a huge, painstakingly crafted origami tree.

But all that disappeared overnight on October 24, 2018. Hopwood Middle School, the largest secondary school in the Northern Mariana Islands, where Orsini teaches, was obliterated.

Super Typhoon Yutu made history as the worst storm to hit United States soil since 1935. The Category 5 storm, with sustained winds of 180 mph, wreaked havoc on the islands of Saipan and Tinian, which are part of the U.S. Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. The storm left thousands of residents without homes. For weeks, fallen power poles and palm trees blocked main roads, while tin roofing and debris blanketed the ground. Saipan International Airport canceled all flights for about a month. South Korea deployed military jets to rescue tourists trapped on the decimated island.

Hurricane Maria made headlines two years ago when it pummeled Puerto Rico, another U.S. territory, but many mainland Americans didn’t hear much about Super Typhoon Yutu. That’s not only because of the scarce media attention, but also because the islands are largely missing from U.S. history textbooks.

Now, a year has gone by since Yutu battered the Northern Marianas, and residents are still reeling, waiting for government funding, watching warily as another storm season passes, and wondering when things will get back to normal.

Orsini holds his classes inside a windowless, coffee-brown, government-issued tent. His homage to the former view: pieces of light-blue butcher paper with drawings of the ocean, sand, and palm trees, hanging from the classroom door and makeshift windows.

Inside Vinni Orsini’s tent classroom Rachel Ramirez / Grist

No strangers to storms

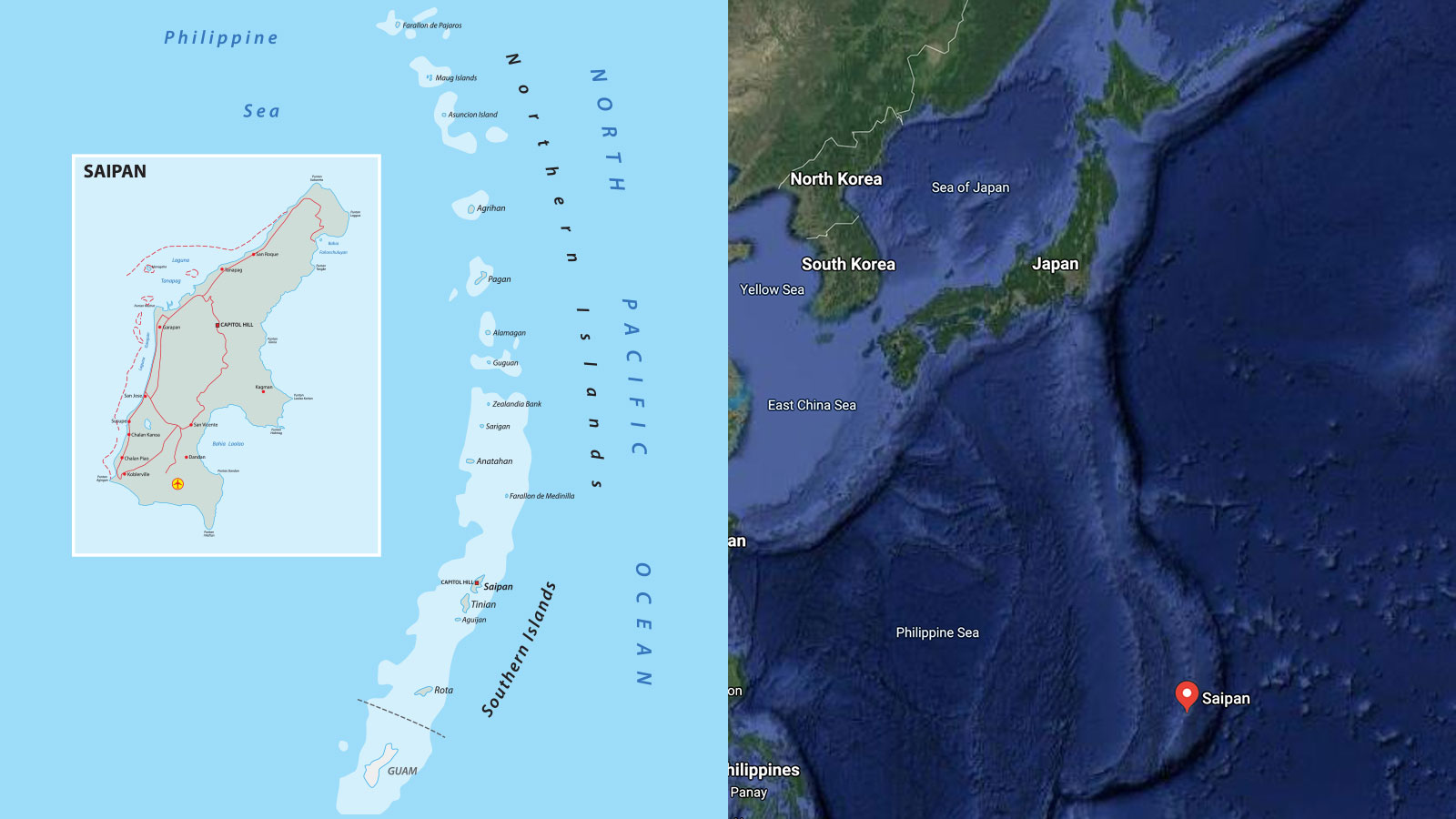

The Northern Mariana Islands — Saipan, Tinian, and Rota — are dots on the map in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, about 1,600 miles east of the Philippines. Saipan played a pivotal role during World War II, when U.S. forces seized the island from Japanese control and used its air base to launch B-29 bombers at the Japanese mainland.

After the war, the Northern Marianas, along with Guam, turned into a hub for U.S. military forces, strategies, and tests. The islands became a U.S. territory in 1975. Over time, Saipan and Guam turned into tropical getaways for tourists coming from all over East Asia.

Today, the Northern Mariana Islands have a population of nearly 55,000 people. Just like in Puerto Rico and Guam, anyone born on these islands is a U.S. citizen.

Rainer Lesniewski / Getty Images / Google Earth

Residents of the Marianas are no strangers to tropical storms. Growing up in the tiny apartment where my parents still live in the village of Chalan Kanoa, just three blocks from the beach, I remember having to evacuate to higher ground when tsunamis would approach. I’ve also experienced a few typhoons, though none as monstrous as Yutu.

I remember the cacophony of heavy rain falling on my neighbors’ tin roofs, branches collapsing from the strong winds, and the thunder that would send my sister and me snuggling up next to my parents as the power went off. In the stifling heat, my dad would fan us with old newspapers. When the rain subsided, we’d load into our car and cool off with the air conditioning.

In 2015, while I was away for college on the mainland, Super Typhoon Soudelor pummeled the Marianas with such force that I couldn’t reach my family for a few days. Soudelor got little mention in the news until it made landfall in Taiwan, but at home, the high winds and heavy rains were devastating and the recovery process was cruel.

When warning came of Super Typhoon Yutu last year, residents prepared by lining up their cars at gas stations, stocking up groceries, charging their electronic devices, and boarding up their houses. President Trump immediately declared a state of emergency, getting federal assistance underway. Still, Yutu was far stronger than people anticipated.

Devastation

By the time I landed in Saipan, exactly seven months had passed since Yutu struck. As the plane approached the terminal, I could see the familiar “Welcome to Saipan” sign from my window seat, and noticed a few letters were missing. The airport looked like a ghost town.

“Hafa Adai, welcome to Saipan, where the local time is 8:14 a.m.,” the captain announced. The doors opened, and I could feel the warm, humid tropical air I’ve known since I was a kid. I hadn’t been home in four years. I’d forgotten what it was like traveling for over 20 hours from the mainland U.S., bouncing from New York City to Japan to Guam, and then from Guam to Saipan.

I was surprised to see that we had to use the airstairs to get off the plane. Then I got a glimpse of the shattered jet bridges next to each gate.

My family was waiting outside the airport with a sign that said “Welcome home, Rachel!” As soon as we got in the car, I asked my dad to take a detour down south, to the part of the island I knew had suffered the most damage. We were greeted with lines of brown refugee tents from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. “People live there,” my mom said. “It’s scattered all over the island.”

We passed by the now-demolished Coral Ocean Point, a hotel and golf resort that my friends and I frequented back in high school. Shards of glass, debris, and coconut trees now littered the parking lot.

Just across the resort, I saw Koblerville Elementary School, where I used to tutor students when I was in the AmeriCorps program. In front of the school, in what used to be a sprawling parking lot surrounded by green grass, were rows of the same tents I’d seen earlier — only bigger. This was the makeshift home of Hopwood Middle School, which relocated here from its original campus overlooking the beach.

Hopwood Middle School’s tent campus Rachel Ramirez / Grist

“Be strong”

Hopwood Middle School holds a long history for many on the island of Saipan. Everybody knows someone who went to school there. My closest friends attended Hopwood. It was the perfect spot: Students would hang out, have lunch, and exchange gossip overlooking the beach. Big events such as the annual Marianas March Against Cancer were always held at Hopwood.

As soon as Yutu died down and it was safe to drive, Orsini headed for the school. Pulling into the parking lot, Orsini was mortified by what he found. He compared the scene to the last Harry Potter movie during the Battle of Hogwarts: Walls were demolished, windows were shattered, roofs caved in, and puddles were all over the classrooms. About 400 feet away, the beach was strewn with tin roofing and debris. Other fragments of the middle school floated on the waves.

Orsini made his way to his classroom. He looked at the date written on the white board — October 23, 2018, the day before the storm struck. His students’ artwork and teacher-appreciation cards were drenched in water. The origami tree lay in a mangled heap.

“I cried. I think all of us did,” Orsini said. “You know, everyone says ‘be strong,’ but there’s really nothing we could do but be strong. We didn’t really have a choice but to suck it up and pack our stuff.”

The long wait

The storm hit low-income residents especially hard. When word of the typhoon spread, wealthier residents could flee the coasts by car and stay with extended families on higher ground, or ride out the storm in hotels and resorts. But for the islands’ immigrant and low-income residents — many of whom live in apartments or houses incapable of withstanding strong storms — the Category 5 typhoon proved catastrophic.

After the storm passed, more than 1,000 residents sought refuge in shelters set up throughout the island, while volunteers stood under the sweltering sun to hand out food and water to those in need. Wait times have become longer at gas stations and grocery stores that residents had to carve out hours just to stand in line.

It would be a month before FEMA grants for businesses, relief programs, and critical infrastructure arrived, while the rest took even more waiting.

Residents of Saipan and Tinian spent months with no electricity and no running water. My parents, who are immigrants from the Philippines, didn’t get electricity and water until January, nearly three months after the storm had passed. They were fortunate, because outside our apartment was a tank filled with rainwater that tenants could use for washing and showering, in case of an emergency. My dad would refill buckets from the tank and carry them back to our apartment. And while some residents had limited access to potable water, he brought home free gallons of drinking water from his job at the Duty Free Shopping Center.

With federal aid slow to reach families, donations and shipping containers of relief goods started pouring in from community members and loved ones from the mainland and neighboring islands. Over time, many families were able to get power generators and stock up on canned goods and drinking water. But immigrant and low-income families were often the last to receive help.

And although schools reopened two months after the storm, there were still daily reminders of its destruction. “When I found out what happened to Hopwood, I was like ‘It’s gone? We’re really not coming back?’” said Emma Chong, an 8th grader at Hopwood. “When I found out we were moving to the tents, I was frustrated and sad. I didn’t want to go to school, but I had no other choice.”

A tent campus

In the first few weeks after Hopwood resumed classes in January, only a few students showed up. When Orsini and other faculty members contacted the missing students’ parents, many of them said that they still didn’t have electricity or water, or basic school supplies, and they didn’t want to send their kids to school dirty and unprepared.

So the faculty found school bags and other supplies and delivered them to the students’ homes — “even shoes,” Orsini said. “Imagine shoes, people who lost their shoes.”

Orsini told me about a time one of his students came to class wearing donated clothes, and another student called out, “Hey, that’s my old shirt!” “That kid stopped coming to school for like a whole two weeks after that,” Orsini said. “At this age, these kids are sensitive.”

Making matters worse, the area around the tent classrooms was treacherous. Not only was it inaccessible for people with disabilities, but students had to navigate huge puddles in the “hallways” between the tents, said Chong, who is 13.

“After school was my big problem. We wait for the bus at a tent, but dirt would fly everywhere, into people’s eyes,” Chong said. “When I got home, I wiped down my face and my arm and there was just so much dirt that came off.”

The slow recovery took an emotional toll. Kim Mendiola, a licensed therapist at the FEMA-backed Community Guidance Center, said that they tried to distract children at shelters with sports, games, and coloring books, but any reprieve was temporary. “When you leave the shelters, you’re constantly reminded of what had happened because there are things lying around,” she said.

Although health and wellness clinics with a 24-hour hotline number were distributed across the island, Mendiola said that early on, there weren’t a lot of takers. “We found out from people in the shelters we talked to that right after the typhoon, families needed to get essentials, families needed to stick together,” she said. “So seeking counseling or outside support may not have been on the front burner at the time, which is completely understandable.”

Back at Hopwood, students were among the first to step up. They carved out time to attend parent-teacher meetings, and even volunteered to go back to the original campus to host a cleanup. They also knew they weren’t the only ones struggling. “We would check in to see if [the teachers] were doing okay,” said Chong. “It never ended in them confiding in us, though, because I know they didn’t want to put that stress on us.”

Orsini said that when faculty broke the news that they were going to be in tents for a while, some of the teachers cried in front of their students. “You know, [teachers] are very reflective,” he said. “When [the students] saw how affected we are, I think that gave them strength that instead of them becoming victims, they became our counselors.”

Rebuild or retreat?

Last month, a new IPCC report found that the Southern Ocean is warming more rapidly than experts previously thought. It was more bad news for small Pacific islands that are already facing the wrath of rising seas, dwindling fishing stocks, and more frequent and severe tropical storms.

Some island nations are taking steps to combat rising seas by passing climate legislation and resiliency plans. Kiribati, which has been inundated by a series of extreme “king tides,” has already put out an adaptation plan on top of its policies to mitigate climate impacts, such as constructing seawalls and resilient infrastructures. During the U.N. General Assembly in September, the Marshall Islands unveiled a plan to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Palau, Guam, and other small island nations are following suit.

The government of the Northern Marianas, however, has not passed any serious policy to combat, or adapt to, the climate crisis. Governor Ralph Torres, a Republican, has thrown his support behind President Trump, whose administration has been weakening federal and state environmental regulations.

Residents, meanwhile, face the stark reality of climate change at the doorstep.

In September, Ed Propst, a representative of the Northern Mariana Islands legislature and an outspoken critic of the government, posed a question on Facebook: “What are your thoughts on relocating Hopwood Middle School? Yes or no?” The post got more than 100 comments, the majority of them opposed to relocation.

Despite rising sea levels and Hopwood’s original campus now sitting in the flood zone, the responses rarely took the climate crisis into account. In fact, commenters were more worried about Hopwood’s land being sold for another high-rise building or a Chinese-owned casino or resort, one of which has been a major source of controversy on the island for years now.

“We must be mindful of the threat of rising sea levels due to climate change,” local activist Cinta Kaipat told me. “But the potential threat of climate change will be indiscriminate, and it will pose the same threat regardless of whoever occupies that venue.”

Money is a serious consideration. The estimated cost of rebuilding Hopwood Middle School in its original location is $27 million. Relocating and building new infrastructure could cost double that amount.

There’s also the question of where a new school might be built. “The original campus holds a dear place in my heart,” said Chong. “But there’s the issue of rising sea levels. It’s either we elevate the school itself or we must move the school to higher ground. But the question is where can we move the school where it’s still in [school district] zoning for all of its students?”

Hopwood Middle School post-Typhoon Yutu

“I just want to go home”

A year after the disaster, many of Saipan’s low-income families and immigrant workers with H1-B2 or CW visas — some ineligible for the federal assistance program — are still waiting for aid to rebuild their homes. A multitude of factors are behind the delay: the remoteness of the Northern Marianas, the fact that it’s a commonwealth rather than a state, and, some residents tell me, a lack of urgency in the local government’s requests for assistance.

Hopwood families, meanwhile, have become more frustrated. Enrollment is down, said Rizalina Liwag, the school’s principal. “Money is an issue,” she told me. “With the students, we’re really hoping to go back to what a school really is, a school that is conducive for learning, a school that has access to all the things schools should have.”

Early this month, Super Typhoon Hagibis brushed past the islands. Residents wondered how long the tent classrooms would last if another storm made landfall.

Propst and other local lawmakers acquired $250,000 to repair Hopwood’s original campus — a fraction of what the full cost will be. The funds came from the annual license fee from the controversial Chinese-owned casino on the island.

“I want the government to take a look around, ask the students what it’s like,” said Chong, who was recently elected as Hopwood’s student body president. “I want them to sit in and have a feel of our experience and what we’re feeling, so they can sympathize with us.”

Back in his temporary classroom, Orsini tried to keep things positive. He was happy that he managed to stay on track and finish his lesson plans last year, despite classes being canceled for a couple months after Yutu. And he was optimistic that he won’t be teaching in a tent much longer.

“We’re definitely not going to be here forever,” Orsini said. “Time heals all wounds.”