Update: After a period of rapid intensification overnight, the National Hurricane Center upgraded Harvey to hurricane status at noon central time on Thursday. The storm is now expected to reach the coastline near Corpus Christi, Texas, late Friday as a major hurricane — the first U.S. landfall of a Category 3 or stronger hurricane since 2005.

In what could become the first major natural disaster of the Trump presidency, meteorologists are sounding the alarm for potentially historic rainfall over the next several days in parts of Texas and Louisiana. This is the kind of storm you drop everything to pay attention to.

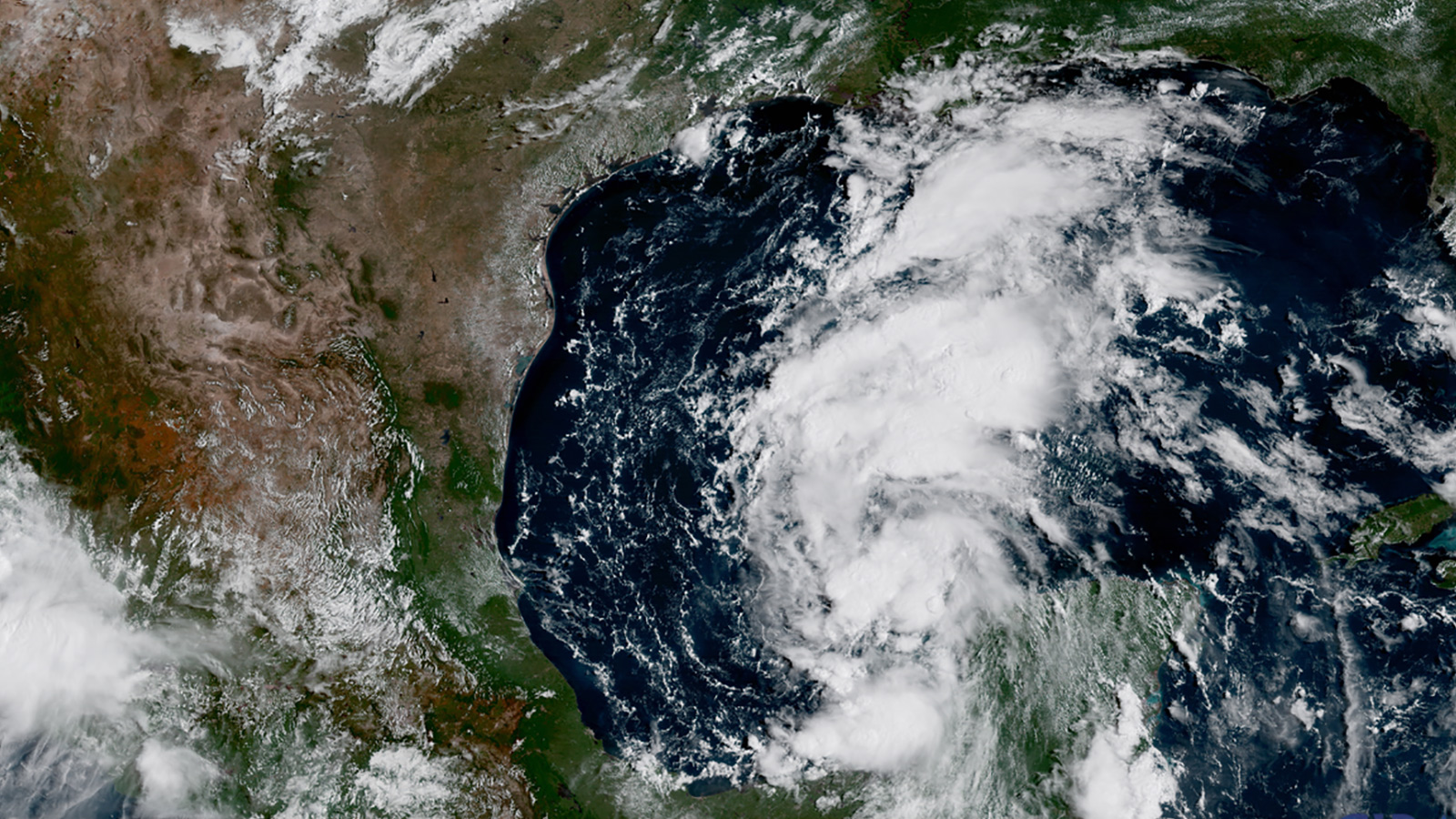

The National Weather Service posted a hurricane and storm surge watch for most of the Texas coastline, and the governors of Texas and Louisiana have begun to assemble emergency response teams. Hurricane hunter aircraft are monitoring the development of the storm, which was just west of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula on Wednesday afternoon.

Conditions in the Gulf of Mexico are nearly ideal for strengthening Tropical Depression Harvey, which could reach hurricane status in the next few days. Water temperatures off the Texas coast are warmer than normal — some of the warmest anywhere in the world right now. Factoring in the state of the atmosphere and ocean, one model estimates the storm’s odds of rapid intensification over the next three days at greater than 10 times the typical chances.

The National Hurricane Center expects Harvey to stall out once it reaches the Texas coastline on Friday, and experts are worried about what might happen next. The official NHC forecast calls for the possibility of more than 20 inches of rain in isolated parts of Texas and Louisiana by next Wednesday, but some individual weather models predict twice that.

Historically, slow-moving tropical storms and low-end hurricanes have caused some of the worst floods on record. In 2001, Tropical Storm Allison stalled over the Houston area, bringing about 10 months worth of rain in just five days. The rainiest day in Houston history was on June 26, 1989, when a slow-moving tropical storm brought just over 10 inches. (Nearby Alvin, Texas, recorded 42 inches in 24 hours in 1979, the all-time U.S. record.)

If Wednesday’s most alarming forecasts pan out, Harvey could be just as bad, if not worse. The heaviest rainfall likely won’t arrive until early next week, which could bring up to four feet of rainfall to parts of the Texas coast.

https://twitter.com/RyanMaue/status/900394113236860929

On Twitter, some meteorologists were agog over Harvey’s rainfall potential, using words like “unsettling” and “borderline unfathomable.” The region just experienced one of the wettest starts to August on record, and the already saturated soil increases the flood risk. All of these signals point to a setup that favors a major disaster. Inland flooding is the leading cause of death in tropical storms and hurricanes.

Floods like the one in the worst Harvey forecasts have come at an increasingly frequent pace. Since the 1950s, the Houston area has seen a 167 percent increase in heavy downpours. At least four rainstorms so severe they would occur only once in 100 years under normal conditions have hit the area since May 2015. With a warmer climate comes faster evaporation and a greater capacity for thunderstorms to produce epic deluges.

Houston has been criticized for unchecked development in its swampy suburbs, which has exacerbated its flooding problem by funneling water along streets and parking lots toward older, lower-income neighborhoods. Just inland, the rapidly-growing corridor of Texas hill country between San Antonio, Austin, and Dallas is sometimes referred to as “flash flood alley,” an increasingly paved area that often sees torrential rainstorms channeled along fast-rising creeks and streams.

Recent rains haven’t been kind to Louisiana, either. Last August, a 500-year rainstorm hit Baton Rouge, Louisiana. And a storm that hit New Orleans earlier this month was so intense locals called it a “mini-Katrina.” Ensuing floods revealed the city’s critically important drainage pump system was partially inoperable, and officials are now contemplating an unprecedented evacuation plan in case the predicted heavy rains materialize. An eastward shift in Harvey’s trajectory by 100 miles or so could force that difficult decision.

Next Tuesday happens to be the 12th anniversary of the landfall of Hurricane Katrina, a storm that many people in the region are still recovering from.

Seven months into the Trump administration, key federal disaster relief positions are still unoccupied: for example, an administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which oversees the National Weather Service. The new FEMA director, Brock Long, was confirmed in late June, three weeks after the start of this year’s hurricane season.

In addition, Trump proposed significant cuts to disaster response agencies and denied emergency funding appeals in several states during his first months in office. A troubled federal flood insurance program covers just one-sixth of Houston residents.

If Harvey’s rains hit the coast with anywhere near the force of the most alarming predictions, we’d be in for disaster. And judging by how New Orleans and Houston have handled recent rains, coupled with the state of federal disaster relief, we’re not ready for it.