This is the second in a series from my conversation with Atlantic tech channel editor Alexis Madrigal about themes and stories from his new book, Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology. You can read part one here.

This is the second in a series from my conversation with Atlantic tech channel editor Alexis Madrigal about themes and stories from his new book, Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology. You can read part one here.

DR: Earlier you mentioned technological momentum. But in a lot of these episodes [from your book], like the one about solar hot water heating, it looked to all appearances like that momentum was building behind a clean technology and then it just … died.

AM: It has to do with the nature of natural gas and oil. There are these boom-and-bust cycles in that industry that tend to just wipe out competition. When it’s expensive, [oil and gas companies are] stockpiling all this money, making billions and billions of dollars, investing into more drilling and refining capacity. The industry overbuilds capacity, then the price falls out, and suddenly you’d be crazy not to be using natural gas or oil. It’s just so cheap. I think of 1999, when I was driving around in Washington state paying a dollar a gallon for gasoline.

Model solar homes in New Mexico. Solar hot water heating took off at the turn of the century but fizzled around 1930 when natural gas became cheap.

Model solar homes in New Mexico. Solar hot water heating took off at the turn of the century but fizzled around 1930 when natural gas became cheap.

The crazy thing about human beings is that we build infrastructure around the low price, not the high price. We get locked in to that infrastructure and it’s difficult for other technologies to break in. You’ve already invested in your HVAC system for your 4,000-square-foot house 50 miles from the nearest city. How do you design a solar system for that house, or an electric car that’s going to fit your needs? It’s a tough thing.

That’s the kind of structural thing you can shape with policy, but it’s wrenching to change. So many, not just companies but individuals, have invested in their personal infrastructure around cheap fossil fuels. That’s why so many people feel like climate legislation is a personal attack on their way of life. They’ve made those bets.

The Lady Hunter well, near Petrolia City, Penn., circa 1880.Library of Congress

The Lady Hunter well, near Petrolia City, Penn., circa 1880.Library of Congress

DR: One of the most fascinating episodes in the book was around the time utilities had been set up to electrify the country. They were facing something we can’t imagine today — a shortage of uses for electricity. They needed to increase demand, and that pushed the development of appliances, even ended up shaping domestic labor patterns.

AM: An epiphany moment for me was realizing that even now in energy statistics, how much electricity gets out to customers is called “electricity sales.” It is a product that they’re selling — the strangest product you could imagine, because you have to use it the second you produce it. It creates a really bizarre industry structure. You need to build for your peak capacity — you need to match loads. That fact alone had a lot to do with how Americans use electricity.

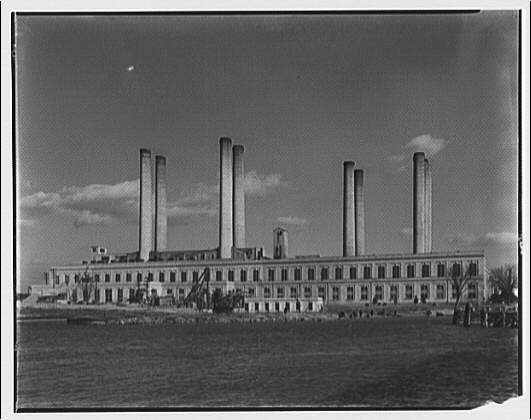

Potomac Electric Power Co. Benning plant, circa 1920.Library of CongressAs Philip Sporn, an influential engineer and the head of a utility in the 1960s, said, the most important loads for you are the loads you invent. What he meant was, if you push out air-conditioning — you realize air-conditioning is going to be a way to sell lots and lots of electricity, particularly into the ticky-tacky suburban houses that just have been built with no thought of comfortable design for climate — you then need to invent balancing loads for the wintertime.

Potomac Electric Power Co. Benning plant, circa 1920.Library of CongressAs Philip Sporn, an influential engineer and the head of a utility in the 1960s, said, the most important loads for you are the loads you invent. What he meant was, if you push out air-conditioning — you realize air-conditioning is going to be a way to sell lots and lots of electricity, particularly into the ticky-tacky suburban houses that just have been built with no thought of comfortable design for climate — you then need to invent balancing loads for the wintertime.

That’s how you get people putting in electric resistance heaters, which is about the dumbest way you can imagine to heat a house. You burn something for heat, convert it to electricity, a really high-quality form of power, and then run it through metal so it gives off heat again. Incredibly inefficient. People recognized this for a long time. It was purely a sales tactic.

It was all sustained by this dream that electrical power would continue to get cheaper and cheaper as it had from 1900 to 1960. We thought we could keep building bigger and bigger plants, largely nuclear plants, and the price of electricity was going to drop to one or two cents a kilowatt-hour.

It’s not totally crazy. From the day these utility executives were born until the day it changed, the price of electricity had been dropping. The culture of utility engineers was grow and build, grow and build. They just could not imagine that the price of electricity would suddenly go up, that the scale of power plants would make them more, not less, expensive. It almost destroyed the entire utility industry of the U.S. in the 1970s.

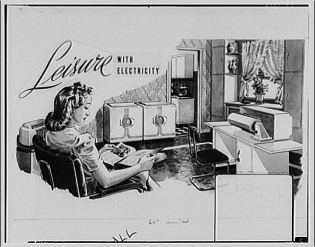

Ad from the Electric Institute of Washington, circa 1946.Library of Congress

Ad from the Electric Institute of Washington, circa 1946.Library of Congress

DR: The promise of ever-increasing electricity was to free human beings from grubby, day-to-day domestic labor. You talk about how it never had the desired effect.

AM: There has been great feminist research on this score. People said, oh, once women have all these appliances they’ll be free to do other things. What happened was that cultural norms for what was considered clean and appropriate went up. Time spent on domestic labor has not gone down, despite the fact that you have all the electric appliances you could ever want.

DR: There’s a class element too. You always need some marker of affluence that is out of reach of the lower classes.

AM: Class played so many interesting roles. At the beginning and middle of the century, virtually every American city had a functioning trolley system. Class and gender played a role in the demise of those systems. The rich controlled them and that created a lot of [populist] backlash. And the rhetoric, particularly centered around protecting upper-class women, didn’t approve people mixing on these trolley cars. If you look at old photos, they were actually packed tight — a lot of class mixing, ethnic mixing. People who sought class and racial purity in their interactions felt driving cars was better. The structure of American race and class relations had far-reaching impacts on our energy system.

Next: Madrigal and I talk energy forecasts (sexier than you think!) and nuclear PR.