Image: Grist

Image: Grist

Americans would like to pay less at the pump. But what would that take? How about another economic crash — or perhaps you’d prefer an ecological one. However the next century shakes out, one thing’s for sure: the ever-growing gap between world oil supplies and demand is making itself felt, and the longer it takes us to break our addiction, the more painful the coming decades will be.

The latest reminder: a State Department cable released by Wikileaks which quotes the former second in command of Saudi Arabia’s national oil company asserting that his country cannot save us from a decline in world oil supplies. Not that he hasn’t been saying this publicly since 2004. Like climate change before it, “peak oil” is an issue that threatens so many of our most-cherished myths about never-ending prosperity and an automobile-dependent civilization that it takes a while to sink in.

It’s not that we’re running out, say the experts, it’s just that we are going to pay dearly to continue to mainline the fuel on which our entire civilization is uniquely dependent.

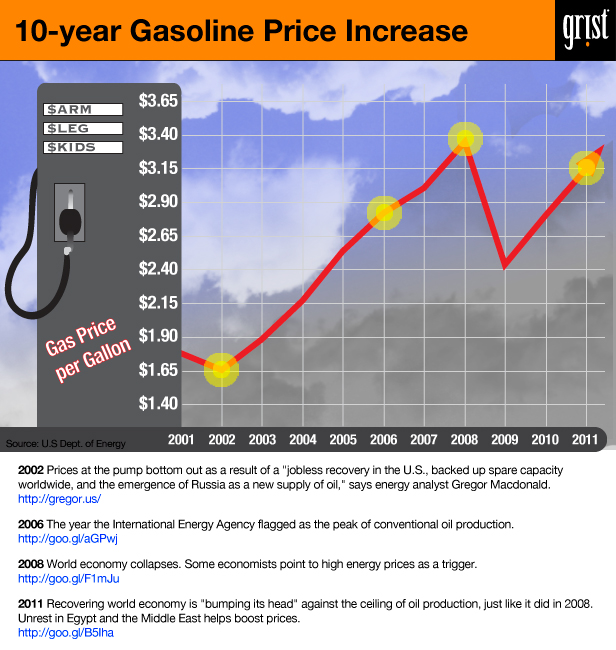

Look at the infographic up top: in 2008, it took the largest economic crash since the Great Depression to bring gasoline prices down, and even then, they didn’t reach the lows seen in 2002. That’s because our capacity to extract oil, and the developing world’s growing demand for it, put a floor on how cheap the stuff could get.

Graph: International Energy Agency

Graph: International Energy Agency

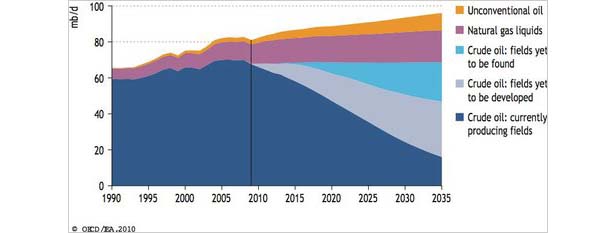

In a post-peak world — see the graph from the usually-conservative International Energy Agency, above, which pegs the peak in crude oil at 2006 — the price of oil tracks the performance of the world economy. When production is flat or declining, the more we want to use, the more we’ll pay, period. (Speculative trading is inevitably a factor in world oil prices, but it’s mostly noise around the overall trend.)

Some economists even argue that the run-up in energy prices of 2008 is one factor that pricked the economic bubble of 2008.

What’s this mean for the future? Overall, the real price of gasoline is only going to go up. Nothing short of an economic slowdown — or a crash — can cap its upward trend now, as the Earth’s billions continue to rush to buy motor vehicles.

Another way to end oil’s rise would be an ecosystem crash, rather than an economic crash, but one could hardly happen without the other. If some other commodity — food, water, a livable climate — turns out to be in even shorter supply than oil from all sources, we may find ourselves using less of the black stuff, unless we use more in order to try and dig ourselves out of the mess we’re in.

Now, what was that the president said about the pressing need for 1 million electric cars on the road by 2015?