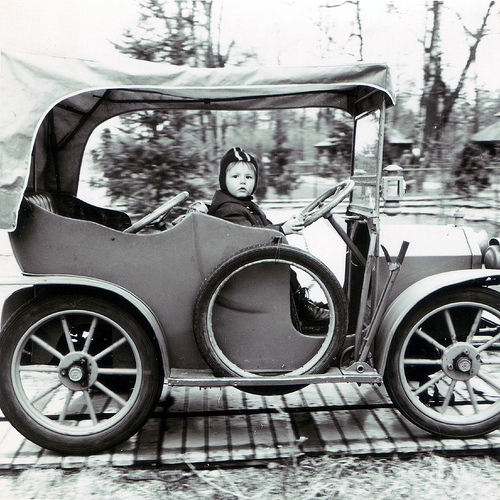

But everybody else does it!Photo: Mario KlingemannOn a recent, rather brisk, walk to church, my 3-year-old daughter, Rosa, asked, “Mom, can we get the kind of car that we keep at our house?” As opposed, that is, to the kind we use for a few hours and then return.

But everybody else does it!Photo: Mario KlingemannOn a recent, rather brisk, walk to church, my 3-year-old daughter, Rosa, asked, “Mom, can we get the kind of car that we keep at our house?” As opposed, that is, to the kind we use for a few hours and then return.

I wasn’t especially surprised by the question. I’ve been expecting it since the day she was born (well, maybe the day after she was born, which was also the day she took her first bus ride). And over the last six months, it has become apparent to her that most people we know don’t ride the bus and walk everywhere they go.

I’m not naive. I fully expect that at some point, my children will rebel against our decision to not to own a car. I expect them to do this because (assuming we don’t see a dramatic shift in attitudes in the next decade) cars convey social status, and because (thanks to a half century of infrastructure built to accommodate them) they are often the travel choice of least resistance.

Right now, Rosa is fine with the bus. She enjoys the adventures and the family face time, and she doesn’t really know anything different. (Transportation conversations with my son, who just turned one, still revolve around vehicle identification — Buh! Buh! Tain! — but I’m pretty sure he’s fine with the bus, too.)

But when Rosa gets to second grade and the cool girls gasp in amazement (and horror!) at her predicament, or when, while walking home from school in the rain, she gets passed by her classmates riding in their parents’ warm sedans, or when she turns 16 and decides to reject everything I hold dear, she might feel differently. Odds are good that she’ll also be influenced by exposure to the auto industry’s propaganda: Cars provide freedom. Cars attract romance. And not only that: Cars are an inevitable, inescapable fact of life.

It is because I know what I am up against that I want to explain to my children — as soon as they start asking — why we live differently than our friends and most of the people they know. If I don’t tell them the truth, who will?

But back to the walk to church.

I told my daughter, in as matter-of-fact and measured a way as I could, why I only drive a car when it’s absolutely necessary. I told her about the effects of cars on our health and the health of the planet: sedentary lifestyles, pollution of air and water, traffic, and noise. (I didn’t get into urban form or destruction of community. Another day.) My little one was convinced. As soon as I finished my explanation, she announced. “I don’t want to have a car!”

This would be fine — great, even — except that she is surrounded by cars and the people who drive them. Moments after our discussion, a ’90-something Mazda with black smoke spewing out of its exhaust pipe zoomed past. “Mommy, Mommy!” she shrieked, visibly shaken. “I don’t want that car to share its pollution with me!”

And it’s not just that I don’t want her to feel terrified every time we step out our front door. I also don’t want her to form judgments about people who don’t live the same way we do. (Those people would be the majority of the residents of her hometown. According to the U.S. Census, 84 percent of Seattle households — including our extended family and closest friends — own cars.) It took her only a matter of minutes after learning about runoff to ask, “Does [insert the name of a family friend]’s car hurt the fish?”

Hmm. Well, yes, but …

My husband said he would have handled the discussion differently. He would have told her that we don’t need a car for our day-to-day life, and that is why we don’t own one. I suppose I could have also put a positive spin on my response and told her that I love riding the bus and walking and prefer to travel that way.

These are both true statements, but they don’t tell the whole story. If I don’t present the other side, the “why” that keeps me going even when it’s raining and I’m schlepping two kids, a shopping bag, and an umbrella, and the bus is 20 minutes late, then I’m setting her up to feel put-upon, or to decide that we’re crazy. (In fact, that seems to be the general consensus of pretty much everyone who knows us.) In other words, I won’t be telling her the truth.

I want to tell my children the truth, but I want to tell it to them in a way that doesn’t scare them, or alienate them from their peers, or cause them to question the choices of everyone else they know. Maybe that’s asking too much. After all, it is crucial that they understand the seriousness of the issue. Maybe I just went about it the wrong way.

So, I’d like some help. How do you teach your children values that stray from the mainstream without alienating them from you or from their community and peers? Or, if your parents raised you with values that you still hold dear: What did they do right?