Smart meters are a revolutionary technology that could save money, save the planet, and enable a switch to renewable energy, so you’d think they’d be really popular with Californians, right? Except that California is also full of right-leaning tin-foil haberdashers and left-leaning hypochondriacs, says the New York Times. The two groups have formed an unholy alliance bent on taking us back to a time before germ theory and/or women’s suffrage, and it’s all because they don’t know the first thing about physics.

Allergic to cordless phones: The smart meters in question use wi-fi to communicate with the utility company — the same thing your laptop uses when you’re at Starbucks — and some folks are concerned about electromagnetic radiation from the wireless signal. The Bay Area residents in question claim to have “electromagnetic hypersensitivity,” or E.H.S., “in which people claim that radiation from cellphones, WiFi systems or smart meters causes them to suffer dizziness, fatigue, headaches, sleeplessness or heart palpitations,” says the Times.

Is there actually a health threat here? Here’s our primer on how electromagnetic radiation does and doesn’t — mostly doesn’t — affect your health.

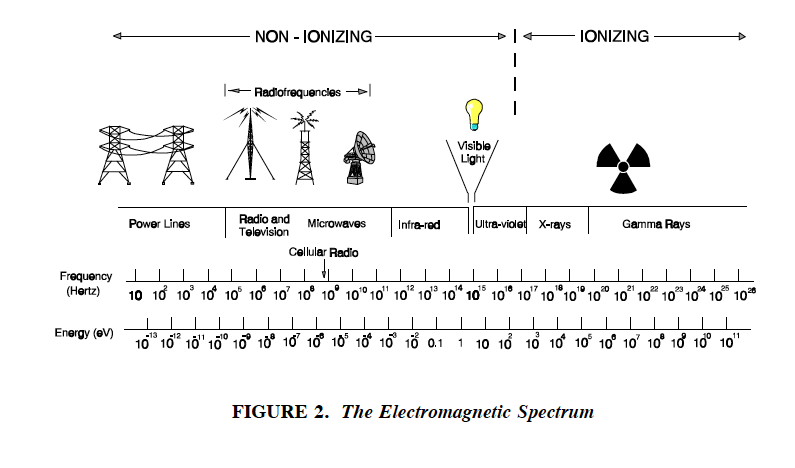

Doesn’t ionize: Most of what we think of as “radiation” — the harmful stuff — has enough power to ionize atoms in your body. That is, it knocks off an electron, which changes the atom chemically. (In case you forgot, atoms consist of protons and neutrons surrounded by a cloud of tiny charge-carrying particles called electrons.) Knocking off an electron is bad: Ionizing radiation can kill cells, damage DNA, and cause mutations and cancer.

Besides the kind of ultraviolet light that causes sunburn, though, almost none of the radiation we encounter on a daily basis — radio, microwaves, visible light — is ionizing. It just doesn’t have enough energy. Think of it like getting hit by a car (bad!) versus getting hit by a bike (probably okay!). In this analogy, the radiation a smart meter puts out would be a child’s tricycle.

At the furthest end of the electromagnetic spectrum, X-rays and gamma rays are powerful enough to be ionizing. But they’re not coming out of your meter, or for that matter your microwave or your phone. In fact, ionizing radiation really messes with circuitry, so a device that emitted ionizing radiation would probably kill itself well before it killed you.

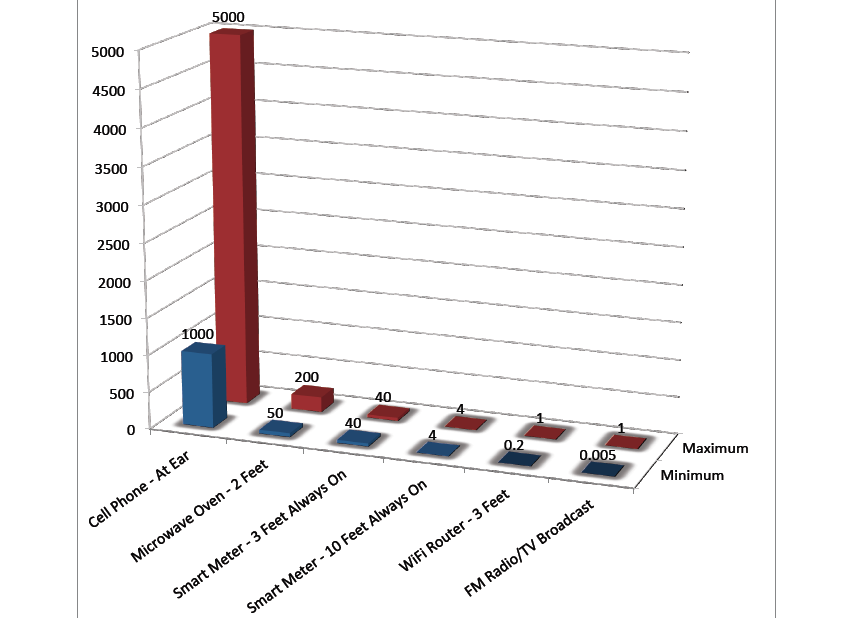

Please stay to the left of the line.Graph: Office of Engineering and Technology, Federal Communications Commission [PDF]

Please stay to the left of the line.Graph: Office of Engineering and Technology, Federal Communications Commission [PDF]

Does heat: Low-frequency radiation doesn’t have enough energy to knock electrons off your atoms, but it can jiggle them around and heat you up; that’s how a microwave warms your food. Obviously there are potential health consequences from being heated up too much, but you’re getting way too little radiation from normal sources to have that sort of effect.

If you’re worried about thermal effects from a smart meter, try this experiment: Stand really close to your wireless router (that’s the box in your house that makes your wireless internet go) until you feel warm. A smart meter would expose you to about four times as much energy if it were constantly transmitting, which it isn’t, but you can figure that you would feel thermal effects in about a quarter of the time. Go on, we’ll wait.

(Do not, incidentally, put your scrotum right on the router, for myriad reasons but especially because sperm are particularly susceptible to thermal effects. You’re probably not going to have any problems from just normal amounts of radiation, but don’t push it, unless you’re deliberately doing your part for zero population growth.)

Exposure to electromagnetic waves (it’s in microwatts per square centimeter, as if you care) is way lower from smart meters than from cell phones.Graph: California Council on Science and Technology [PDF]

Exposure to electromagnetic waves (it’s in microwatts per square centimeter, as if you care) is way lower from smart meters than from cell phones.Graph: California Council on Science and Technology [PDF]

Could have other effects that may or may not exist: So now we come to “non-thermal effects,” the bête noire of the anti-electromagnetic movement. Non-thermal effects, if they are a thing, happen when energy from a weak electromagnetic wave, one that doesn’t have enough power to have any thermal effect, jostles molecules and interferes with their oscillation. This could potentially have negative effects, like causing or exacerbating cancers. The jury is out on whether they’re a thing, though — they’re like dark matter or ghosts, in that they’d explain a few things but are hard to prove or disprove.

What about those symptoms? There’s no good evidence for health consequences from the level of electromagnetic radiation you’re normally exposed to, which is governed by pretty conservative regulations. One study did show a correlation between cell phone use and cancer, but didn’t establish whether the one caused the other. But here’s what one protestor had to say about that in the Times:

“No one who’s been affected by this is willing to wait for the science to catch up with the causal link,” said Elisa Baker-Cook, 40, a former journalist from Scarborough, Me., who is leading protests against Central Maine Power’s meters. “When someone is sensitive to wireless, they don’t need a causal link. Our bodies’ reaction is the causal link, and we learn to trust that.”

It’s certainly the case that people report sensitivity to electromagnetic radiation. Whether that’s what they’re actually experiencing is another matter — under lab conditions, “sensitive” folks can’t detect the presence of radiation any more reliably than people who didn’t report sensitivity [PDF]. And you also have to watch out for the nocebo effect, where people who believe they have an illness or are being exposed to something harmful are more likely to experience symptoms.

That said, perhaps the best solution is the one proposed in the Times by California state assemblyman Jared Huffman: an opt-out plan for wireless smart meters (or rather, an opt-in plan to have hard-wired ones instead). Even if the meters aren’t actually harming your health, maybe you should be allowed to avoid them if you feel they are — just as you’re allowed to avoid wifi or cell phones in your house.

What about our freedoms? These aren’t the only concerns about smart meters, just the most quackish. One Tea Party-affiliated objector quoted in the Times described the meters as “the sharp end of a very long spear pointed at your freedoms.” Jonathan Hiskes wrote about some of the concerns about privacy and cost (as well as health) here in November:

The privacy concerns are the thorniest ones. The point of the meters is to collect vast amounts of user data that will let homeowners do more with less energy. That digital network — just like online banking or online voting — has triggered Big Brother anxiety that threatens to become a major barrier to the smart grid.

“Quite frankly you really don’t need to know if I ran my margarita blender 40 times in one night,” one commenter put it.