This is part of a series on distributed renewable energy posted to Grist. It originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

The difference between clean energy policies with a democratizing influence and the bewildering U.S. system can be illustrated with a close look at the federal investment tax credit for solar power. The investment tax credit returns up to 30 percent of a solar photovoltaic (PV) system value to the developer, and the credit can be carried over for five years (until 2016, when the entire tax credit may expire as it has in the past).

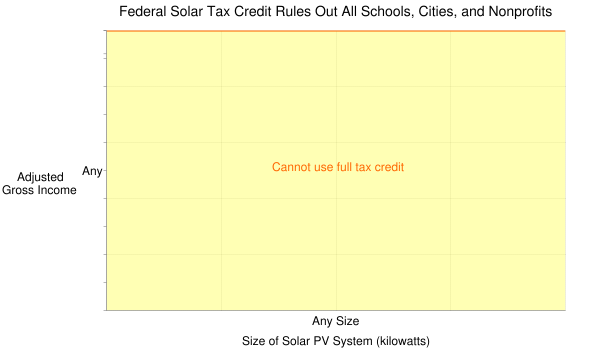

Unfortunately, many of the institutions and individuals that could invest in solar power are not able to use the credit simply because it’s based in the tax code.

For the moment, we’ll leave out the obvious non-taxable entities like schools, nonprofits, governments and focus just on the impact of the federal solar incentive on residential solar. A large portion of the thousand of megawatts of solar being installed in California, Colorado, and other large solar markets is going on home rooftops.

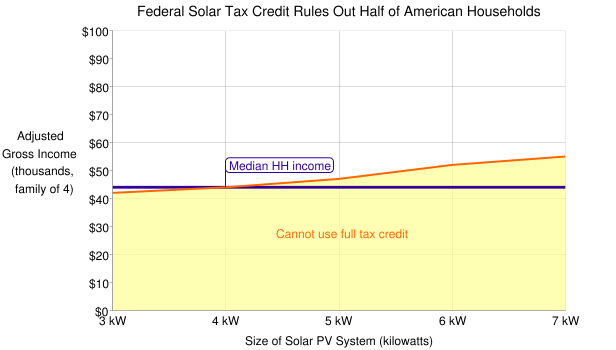

A typical residential solar PV array is around 5 kilowatts (kW), with a cost of $41,000 ($8.20 per watt), so the federal tax credit has a maximum value of $12,300.

A family of four in the U.S. with the median family income of $44,000 has an estimated tax burden of $2,000 and would require just over six years to successfully absorb the tax credit on a 5 kW residential solar array. But tax law only gives them five years to use the credit (and the credit may expire again in 2016, as federal renewable energy incentives have in the past).

The picture is only worse for those families with lower income (and tax liability), effectively ruling out half of Americans from using the solar tax credit.

Filling status makes little difference, with slightly more than half of individual filers able to use the full federal tax credit than married, joint filers. (Note: the tax estimations assumed that the family of four would claim zero exemptions but would claim any deductions or credits associated with having two children).

Ultimately, a great number of Americans are not able to finance solar projects economically simply because the incentive is based in the tax code.

To be fair, a significant drop in the price of solar PV (from $8.20 to $5.00 per watt, for example) could increase the number of Americans who could capture the full credit for a given system size (reducing the non-participants to 45 percent of Americans), but the tax credit still leaves out millions of potential individual solar investors.

And of course, schools, cities, and nonprofits have always been left out entirely.

In contrast, incentive schemes that don’t depend on tax credits (such as production payments) can be used by anyone. Yet another reason the U.S. should reconsider using the tax code for its renewable energy incentives.