We already do, thank you very much.Photo: Web TrendsThis is the first installment of a regular column about all things bicycle by Elly Blue.

We already do, thank you very much.Photo: Web TrendsThis is the first installment of a regular column about all things bicycle by Elly Blue.

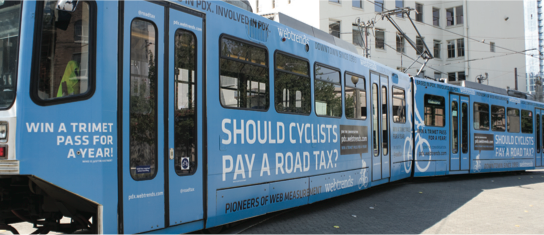

“Should cyclists pay a road tax?”

That was printed on the side of one of Portland, Ore.’s MAX light rail trains as it sailed back and forth across the region for six months in 2009.

The question was designed to provoke, and it did. “We already do!” I would grumble every time I saw it.

It’s true. And, fair being fair, we overpay.

Say you own a car. You’re shelling out an average of $9,519 this year, according to the American Automobile Association (most other estimates are higher). Some of those costs — a percentage of gas, registration, licensing, and tolls — go directly to pay for roads. And it hurts. You doubtless feel every penny.

The thing is, that money only pays for freeways and highways. Or it mostly pays for them — a hefty chunk of change for these incredibly expensive, high maintenance thoroughfares still comes from the general fund.

Local roads, where you most likely do the bulk of your daily bicycling, are a different story. The cost of building, maintaining, and managing traffic on these local roads adds up to about 6 cents per mile for each motor vehicle. The cost contributed to these roads by the drivers of these motor vehicles through direct user fees? 0.7 cents per mile. The rest comes out of the general tax fund.

This means that anyone who owns a home, rents, purchases taxable goods, collects taxable income, or runs a business also pays for the roads. If you don’t drive a car, even for some trips, you are subsidizing those who do — by a lot. The best primer on this is economist Todd Litman’s highly readable 2004 report “Whose Roads.” (It’s also the source for most of the figures in this column. Download the PDF here). A journalist recently crunched the numbers in Seattle and found the discrepancy in 2010 to be as wide as ever.

There are many reasons for cities to encourage bicycling, and the economic argument is one of the best. Every time somebody gets on a bicycle instead of in a car, the city saves money. The cost of road maintenance is averaged at 5.6 cents per mile per motor vehicle. Add the so-called external costs of parking (10 cents), crashes (8 cents), congestion (4 cents), and land costs and that’s another 28 cents per mile! Meanwhile, for slower, lighter, smaller bicycles, the externalities add up to one meager cent per mile.

The average driver travels 10,000 miles in town each year and contributes $324 in taxes and direct fees. The cost to the public, including direct costs and externalities, is a whopping $3,360.

On the opposite pole, someone who exclusively bikes may go 3,000 miles in a year, contribute $300 annually in taxes, and costs the public only $36, making for a profit of $264. To balance the road budget, we need 12 people commuting by bicycle for each person who commutes by car.

The numbers continue to be astonishing when you consider the cost of bicycle infrastructure. It consists mainly of paint and is dirt cheap by comparison to any other sort of transportation project. Portland has transformed itself into a bicycling mecca while allocating less than 1 percent of its transportation budget to bikes each year — with critics fighting tooth and nail against every penny spent.

In tight economic times, when it’s hard to scrape together the cash to fill potholes, even this low level of bicycle spending is often put on hold. But what if, instead, the road tax overpaid by bicyclists were invested into making city streets safer, more comfortable, and more convenient for bicycling? New York City has been doing just that, resulting in tens of thousands of people taking to the streets on two wheels and — if those people would otherwise be making those trips by car — saving the city a whole hell of a lot of cash.

Yet the myth of bicyclists as freeloaders is gaining ground. Proposals for bicycle registration schemes crop up every few months, usually from conservative politicians looking for someone to blame, but also at times from well-meaning bicycle advocates. Never mind that no such program has ever managed to pay for its own administrative costs. Nothing is accomplished by putting up barriers to active transportation. Instead, these barriers need to be removed.

Cities — and taxpayers — can’t afford not to invest in bicycling.