Yesterday I wrote about three policies that have enduring public support but can’t catch a break in Washington, D.C., particularly in the Senate: promoting clean energy and fighting climate change, taxing the rich, and reducing corporate influence in politics.

Why is it that senators won’t act on what the public wants in these (and other similar) cases?

Larry Bartels: “Economic Inequality and Political Representation” [PDF]

Larry Bartels: “Economic Inequality and Political Representation” [PDF]

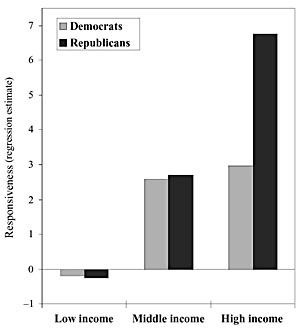

Obviously there are multiple causes and complexities, but at root the answer is pretty simple: Politicians are disproportionately and overwhelmingly responsive to the minority of Americans who have lots of money. Princeton political scientist Larry Bartels has done some great work [PDF] on this. Kevin Drum summarizes it thusly:

Using data from voting records in the early 90s, [Bartels] shows that the responsiveness of senators to the views of the poor and working class is … zero. Or maybe even negative. And that’s true for both parties. The middle class does better — again, with both parties — and high earners do better still. In fact, they do spectacularly better among Republican senators. And this disparity has almost certainly gotten even worse over the past two decades.

Both parties ignore the poor and working class, both are moderately heedful of the middle class, and Republicans are extremely solicitous toward the wealthy.

What explains this state of affairs — the domination of political space by the wealthy? Lots of people are inclined to point to outright corruption and moral turpitude, and there’s certainly plenty of that, but there are other, more subtle things going on as well.

In a 2009 paper in the journal Perspectives on Politics, two political scientists at Northwestern, Jeffrey Winters and Benjamin Page, asked whether we can fairly be said to have “Oligarchy in the United States?” They define oligarchy as a political system in which “the wealthiest citizens deploy unique and concentrated power resources to defend their unique minority interests. … Oligarchy refers broadly to extreme political inequalities that necessarily accompany extreme material inequalities.” (And we definitely live in an age of extreme material inequalities.)

Oligarchy doesn’t require a conspiracy — the wealthy don’t have to meet in back rooms and twirl their mustaches while they smoke cigars and cackle evilly:

A distinctive quality of political power based on wealth is that it does not depend upon extensive investments of time or action by wealthy individuals themselves, nor does it rely for its potency on mobilization and coordination among oligarchs. The wealthy often control large organizations, such as business corporations, that can act for them. They can hire armies of professional, skilled actors from the middle and upper-middle classes who labor as salaried advocates and defenders of core oligarchic interests. In modern societies these actors are often denizens of foundations, think tanks, politically connected law firms, consultancies, and lobbying organizations. Sometimes they are politicians or officials recruited and funded by the wealthy. They blend smoothly into the complex give and take of pluralist politics, but their character, focus, and effect is different: it is to advance the basic material interests of the wealthy.

Sounds familiar, huh?

Nor is oligarchy incompatible with democracy; indeed, the two can and do co-exist. Oligarchs don’t need to exert iron control over all policy. It’s perfectly possible for there to be a circumscribed arena of pluralism around, for instance, social issues. Oligarchs only exert influence over areas germane to their long-term financial interests, specifically: international economic policy, monetary policy, tax policy, and overtly redistributionist policies.

And their control is not heavy-handed. They exercise their power in a number of ways: throwing money around via lobbying and campaign donations, of course, but also getting people on the judicial bench and, most interesting from my perspective, shaping elite opinion.

Winters and Page write:

One of the most important and best-replicated findings of media research is that official sources — especially the U.S. president and his administration — tend to dominate political news in the mass media. Most Americans, most of the time, have to rely upon officials — and on ostensibly nonpartisan “experts” and commentators who generally speak the same language — for facts and interpretations about world and national politics. To the extent that officials are selected or influenced through electoral and lobbying activities by the wealthy, it is plausible that public opinion is indirectly shaped by an oligarchy. More directly, oligarchs could orchestrate information campaigns through advertising and through friendly or subsidized communicators.

Yeah, that sounds familiar too. I think there are also subtler things going on in political media. This bit from George Packer’s masterful recent piece on the Senate caught my eye:

One day in his office, Udall picked up some tabloids from his coffee table and waved them at me. “You know about all these rags that cover the Hill, right?” he said, smiling. There are five dailies — Politico, The Hill, Roll Call, CongressDaily, and CQ Today — all of which emphasize insider conflict. … News about, by, and for a tiny kingdom of political obsessives dominates the attention of senators and staff, while stories that might affect their constituents go unreported because their home-state papers can no longer afford to have bureaus in Washington.

It’s often noted that the political media’s focus on insider gossip and hyperspeed news cycles has the effect of turning everyone’s attention to tactics and spin over policy and substantive exchange of ideas. Power brokers play to the media, the media plays to power brokers, and a relatively small group who enjoys the blood sport of politics looks on, keeping score.

That’s all true, but modern political media also has another effect: It circumscribes the range of debate and reinforces Beltway center-right orthodoxy. Nowadays, every political journalist is in the business of evaluating the tactical implications of every new statement or bill or leak or Sarah Palin Facebook post or whatever. They can’t possibly assess every maneuver or situation with a fresh eye when there are a dozen a day and they have to determine who won the morning, noon, and night. So what do they do? They reach for the trusted heuristics, the old narratives they’re confident fall within the sphere of consensus.

What are those narratives, which suffuse the air in the Beltway like oxygen? You know: Democrats are weak on national security. Social Security is in crisis and eventually the American people are going to have to grow up and accept benefit cuts. Military spending can’t go down, ever. Unions are bothersome relics. Republicans care about the de

ficit. Regulation is burdensome, economically harmful, and unpopular. Basic functions of government, taxing and spending, are discredited liberal indulgences.

And so on. No matter how far from reality these narratives drift — and they’re pretty damn far from reality now — they are self-perpetuating and virtually impossible to dislodge. Journalists need these heuristics for evaluating the endless daily stream of political maneuvers. The thread that runs through all these narratives is not so much conservatism, certainly not libertarianism, but a kind of economic royalism: Conventional wisdom in D.C. is simply far more attuned to the interests of the wealthy than public opinion broadly.

And why wouldn’t it be? Members of the political and media establishments are disproportionately white, college-educated, and affluent. They mingle socially and professionally and develop a shared language and set of concerns. Most senators are rich white people and live lives filled with other rich white people. They might not recognize themselves as rich, of course. It was more than just a gaffe when Sen. David Vitter (R-La.) said that “virtually everyone” makes over $250,000 a year, it was a window into a world where the beleaguered Merely Rich envy the Extremely Rich. But make no mistake, in a country where the median income is around $52,000, $250,000 is rich. Rich people populate senators’ social circles; they get in for appointments at their offices; they make big campaign donations; they fund the think tanks that feed senatorial staffers policy ideas and political attacks. Officialdom is filled with wealthy people, often people who have become wealthy in industries they will go on to regulate as lawmakers … and then lobby for after they leave.

Under those circumstances, one hardly needs to shape opinion in favor of the wealthy; it shapes itself. It yields a milieu in which a group of Democratic senators can, by opposing policies supported by the vast majority of Americans and their own constituents, earn themselves the coveted title “moderate.”

Bob Herbert had a powerful column last week about the pain ordinary people are suffering:

The American economy is on its knees and the suffering has reached historic levels. Nearly 44 million people were living in poverty last year, which is more than 14 percent of the population. That is an increase of 4 million over the previous year, the highest percentage in 15 years, and the highest number in more than a half-century of record-keeping. Millions more are teetering on the edge, poised to fall into poverty.

Yet in D.C., it’s the long-term deficit that’s the problem. In D.C., even an extension of unemployment benefits is controversial. In D.C., Joe Lieberman is organizing another “gang” to defend tax cuts for the wealthy. In D.C., it’s the angry rich, not the suffering poor, whose voices dominate.

Such is the essence of progressive politics: to organize the other 98 percent of people to wrest public benefit from the wealthy 2 percent. The debate over climate and energy policy has often proceeded as if it is orthogonal to that larger progressive struggle, as if a “clean environment” is kind of boutique concern of coastal elites. But there’s a reason the Beltway ignores public opinion on climate and energy, the same reason it ignores public opinion on taxes: climate and energy policy is inherently progressive. Or so I shall argue in my next post.