As you may have heard, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) dropped a hint last week that he may still try to get a Renewable Electricity Standard (RES) into the Senate energy bill. According to Reid, there are two Republicans talking about supporting it, one of them likely Sam Brownback (R-Kansas). The RES in question would presumably be the one that passed the Energy Committee in June of last year, which is extremely … modest, to put it charitably. Still, it’s something. Does it has a shot?

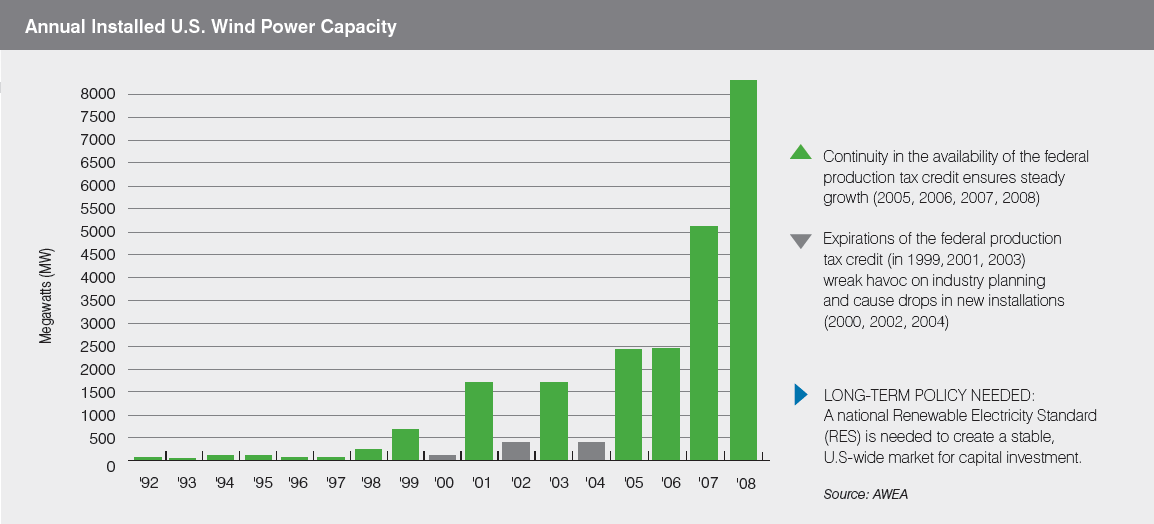

Policy-wise, it should be a no-brainer. To date, U.S. clean energy industries have been supported, if at all, by tax credits, which tend to come and go contingent on the political atmosphere and the mood of the Ways and Means Committee. Here’s a chart from the American Wind Energy Association that shows the effect see-sawing credits have on the industry (click for larger version):

An RES, even a modest RES, would be the first stable, long-term policy to support clean energy in the U.S. in, well, ever. It would enable serious long-term investor planning and spur some of the new infrastructure and industries America will need when we decide to get serious about climate change.

And it can’t come soon enough: according to a new report from Ernst & Young (PDF), China has passed the U.S. for the first time to become the most attractive destination for global clean energy investment:

This issue sees the US relinquishing its top position held since 2006 — dropping two points to slip behind China, effectively crowning the Asian giant the most attractive market for renewables investment. This follows the failure in the US Senate’s proposed energy bill to include a Federal Renewable Energy Standard (RES) provision.

This on the heels of last month’s exasperated declaration from Deutsche Bank — which devotes $6 or $7 billion to low-carbon products — that it is taking its clean energy capital elsewhere. And then there was this extraordinary statement last week from Lew Hay, CEO of NextEra Energy (America’s largest clean energy developer):

With an RES, we estimate that we would invest approximately $1 billion more per year in wind and $1.5 billion in solar. That would translate into roughly 40,000 jobs over the next five years.

Clean energy advocates are always going on about how private capital is “sitting on the sidelines,” waiting for a reliable policy signal. This is what they’re talking about.

What about the economy? Well, the U.S. is mired in a demand-side recession. Factories and workers are laying idle. An RES will spur demand for clean energy up and down an enormous supply chain and spur deployment of private capital without costing the federal budget anything. A quarter of the RES in the Energy Committee bill can be met with energy efficiency, which is also labor intensive and “can’t be offshored,” as they say.

According to a new report from Navigant Consulting (PDF), an RES of 25 percent by 2025 (much more ambitious than what’s on the table in the Senate) would support 274,000 new clean energy jobs. Furthermore, those jobs would be created in every region of the country, including the Southeast, where opposition to an RES tends to be centered.

Is it popular? Any politician should be so popular. Last month in a Pew/National Journal poll a whopping 78 percent of respondents supported an RES, including 70 percent of Republicans and 77 percent of Independents. Requiring utilities to use more clean energy has been one of the most reliably popular energy policy options for years. The last few months have seen a stream of editorials, signed letters, and statements of support of the policy from prominent conservatives and industry groups.

Not many policies get this kind of bipartisan support these days. People are fond of saying energy should be a bipartisan issue and surely reasonable people can agree, etc. Well, here it is, happening.

But … you knew there was a but, right? … it’s tough to see it passing this year. The harsh math of the filibuster means Harry Reid depends entirely on Republican votes. Time after time this session, this or that Republican has held out the prospect of cooperation; time after time, they’ve yanked it away in the end.

But … you knew there was a but, right? … it’s tough to see it passing this year. The harsh math of the filibuster means Harry Reid depends entirely on Republican votes. Time after time this session, this or that Republican has held out the prospect of cooperation; time after time, they’ve yanked it away in the end.

Right now, Republicans are in the catbird seat. By all indications they are heading for historic victories in the 2012 midterms. Every poll is swinging their way and the Democrats are having one crappy news cycle after another. What conceivable incentive do they have to allow Dems a legislative victory at this late hour, right when they’re on the ropes?

I mean, in a period of 10 percent unemployment, the GOP fought against unemployment benefits. You think they won’t block an RES? They’re now arguing against R&D tax credits and infrastructure spending, two policies they have (rhetorically) supported for years. You think they won’t turn their back on an RES?

Few people on the center left — and I include both Obama and Reid in this — seem able to get their heads around what the GOP has become. They keep thinking there are policy compromises so obviously in the public interest that Republicans will feel a sense of shame and call a time out on partisan warfare. By now, though, it should be clear beyond all doubt that Republicans have no interest in doing so. It’s got nothing to do with policy or the public interest. Maximal obstruction is proving electorally successful for the GOP and getting power back is their sole and overriding priority. Pressure on their members not to cross the aisle will be overwhelming. They want to destroy Obama and the Dems. That’s it. That’s really it.

But hell. Maybe Reid is right that if he approaches Republican senators during the lame duck session they’ll be free of electoral pressure and ready to get something done an RES. Maybe I’ll be proven wrong and readers will be right to scold me for seeing the Congressional GOP as a purely malign force in contemporary energy policy. I certainly hope so. I commend all the work being done to make it so and encourage anyone who can to join that work. But at the moment my pessimism-of-the-intellect is sitting on top of my optimism-of-the-will, giving it a wedgie.