As if the Deepwater Horizon disaster weren’t enough, this year’s dead zone is one of the largest ever.Graphic: Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium

As if the Deepwater Horizon disaster weren’t enough, this year’s dead zone is one of the largest ever.Graphic: Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium

Deep in the Gulf of Mexico, plumes of dispersed oil linger, wreaking unknown damage on one of the globe’s most productive ecosystems.

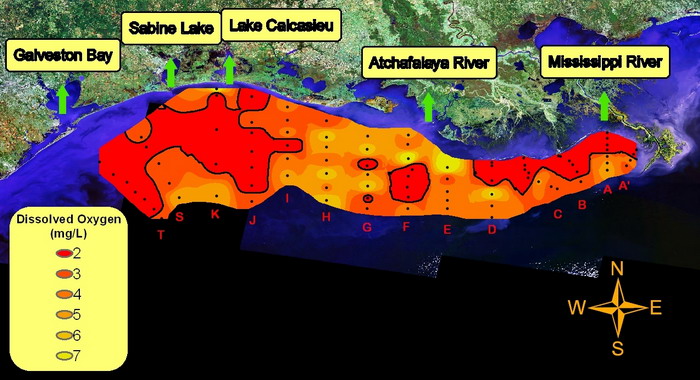

But BP’s oil isn’t the only destructive substance that gushed into the Gulf this year. This summer — and every summer since the early 1970s — a large amount of fertilizer leached out of Midwestern corn fields and into streams that drain into the Mississippi, eventually making its way to the Gulf. Once there, it feeds gigantic algae blooms that, as they decompose, suck up oxygen and squeeze out sea life. Scientists call this process “hypoxia.”

Researchers from Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium have been measuring the Gulf’s hypoxic zone since 1985. Every year, they gauge the size of the “dead zone” by heading out on a research ship called the Pelican to measure oxygen levels near the Mississippi’s mouth. The team has just filed its report [PDF] for this year. Their verdict: “one of the largest ever.”

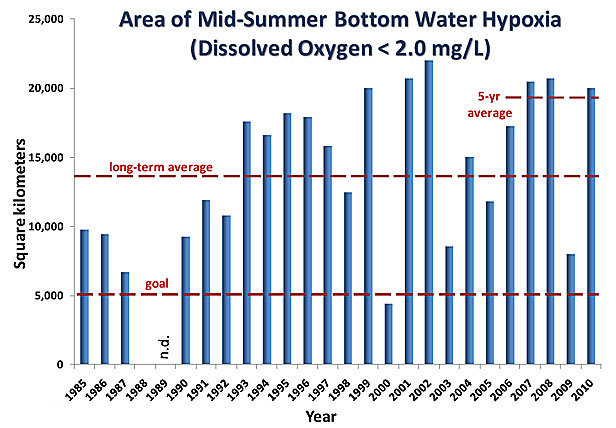

The team concluded that this year’s dead zone covers 7,722 square miles — an area roughly equal to the landmass of Massachusetts, and the sixth-largest area since the group started measuring. As the chart at the bottom of this post shows, this year’s dead zone fits in with a disturbing upward trend since 2006, when government-mandated ethanol production began diverting ever-greater amounts of corn into car-fuel production.

What does ethanol have to do with the dead zone? Responding to higher corn prices, farmers have been moved to shift more land into corn production and use more chemical fertilizers to boost yields. Corn plants typically only take up 40 percent of the synthetic nitrogen applied by farmers, leaving the rest to wash out into streams and down to the Gulf.

Last year, the Gulf got merciful respite. Tropical storms came at just the right time to diffuse fertilizer pollution, resulting in the smallest dead zone since 2000. This year, recent storms have just broken the hypoxic areas into clusters. As the report puts it:

Instead of the usual continuous band of low oxygen along the coast, this summer’s distribution was a patchwork of several areas. The scientists think that this result is because of recent tropical storm activity.

And this summer’s dead zone may actually be the largest ever — bad weather stopped the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium’s ship from fully measuring the affected area. “The total area probably would have been the largest if we had had enough time to completely map the western part,” the consortium’s executive director, Nancy Rabalais, said.

The researchers directly tie the size of the dead zone to industrial corn production in the Midwest. “The size of the hypoxic zone and nitrogen loading from the river is an unambiguous relationship,” one researcher remarked. “We need to act on that information.”

Of course, we’re doing the exact opposite. For the health of the Gulf ecosystem, researchers hope to see the size of the dead zone drop significantly by 2015. But ethanol mandates and surging demand from China all but guarantee higher corn prices for years to come. And that means ever more chemical fertilizers will be dumped on Midwestern corn fields — and ever larger dead zones will bloom going forward. To supply the world with cheap low-quality meat and and ourselves with highly subsidized, low-quality fuel, we seem content to kill off ever larger swaths of a vital natural asset. We’re behaving not unlike a rich kid who blows his trust fund on Scotch, cocaine, and casino chips.

It also bears noting that nitrogen-fed dead zones like the one in the Gulf — the largest one of 400 worldwide — don’t just devastate local fish habitats. They also contribute to climate change. According to a study published this spring in Science, oxygen-starved areas of the ocean emit significantly more nitrous oxide into the atmosphere than healthy waters. Nitrous oxide is a greenhouse gas some 300 times more potent than carbon.

Graphic: Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium

Graphic: Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium