The Colorado River hasn’t reached the sea in ages. Is there hope left for this storied but manhandled river? Jonathan Waterman, author of Running Dry: A Journey from Source to Sea Down the Colorado River, brought together two experts from either end of the river to talk about what’s happened to the river over the years, and how to get more water flowing in the future.

The Colorado River hasn’t reached the sea in ages. Is there hope left for this storied but manhandled river? Jonathan Waterman, author of Running Dry: A Journey from Source to Sea Down the Colorado River, brought together two experts from either end of the river to talk about what’s happened to the river over the years, and how to get more water flowing in the future.

Brad Udall is the director of Western Water Assessment, based out of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) offices in Boulder, Colo. Osvel Hinojosa works as director of the water and wetlands program from the Mexican environmental group Pronatura.

Jonathan Waterman: So while you’re both involved a lot with agencies that have to do with safeguarding water and the Colorado River throughout the basin, we’ve also chosen to talk with you because you live, essentially, at opposite ends of the spectrum — in the state of Colorado near the headwaters, and then in the Mexican delta, where the river runs dry. And these are ideal positions to show the range of river issues. So if you guys could introduce yourself and your work, especially your work related to the Colorado River.

Jonathan Waterman: So while you’re both involved a lot with agencies that have to do with safeguarding water and the Colorado River throughout the basin, we’ve also chosen to talk with you because you live, essentially, at opposite ends of the spectrum — in the state of Colorado near the headwaters, and then in the Mexican delta, where the river runs dry. And these are ideal positions to show the range of river issues. So if you guys could introduce yourself and your work, especially your work related to the Colorado River.

Brad Udall: I work for the University of Colorado where I’m on the research faculty. I run a program here called the Western Water Assessment which is supported with NOAA funding. We utilize a team of 30 researchers to look at climate issues in the American West with the idea to help folks — decision-makers make better decisions with respect to climate. And when I say climate I mean what we can learn about past climate — for example, tree-ring studies — what we know might happen in the next six to 12 months, and what we might know into the future, say 100 years out, because of climate change. The 30 people that are associated with this program range from climate scientists to economists to policy folks, environmental scientists, you name it — we’ve got access to them, and we’re trying to produce the best science we can. In particular, my area of expertise is the Colorado River basin, and I’ve been party to a number of studies that look into the future of this river.

Brad Udall: I work for the University of Colorado where I’m on the research faculty. I run a program here called the Western Water Assessment which is supported with NOAA funding. We utilize a team of 30 researchers to look at climate issues in the American West with the idea to help folks — decision-makers make better decisions with respect to climate. And when I say climate I mean what we can learn about past climate — for example, tree-ring studies — what we know might happen in the next six to 12 months, and what we might know into the future, say 100 years out, because of climate change. The 30 people that are associated with this program range from climate scientists to economists to policy folks, environmental scientists, you name it — we’ve got access to them, and we’re trying to produce the best science we can. In particular, my area of expertise is the Colorado River basin, and I’ve been party to a number of studies that look into the future of this river.

Osvel Hinojosa: I work for Pronatura in Mexicali, based mostly in the delta region and upper Gulf of California. And we have been working on the restoration of the Colorado delta for almost 10 years now, working with organizations from both sides of the border. We have been doing basic research to understand the issues and how can we restore the delta that is feasible, and then we have also been involved in active restoration and community work, monitoring, and more recently a lot on the water issues. We’ve created a water trust with some other organizations to purchase water and restore the flow in the Colorado River delta.

Osvel Hinojosa: I work for Pronatura in Mexicali, based mostly in the delta region and upper Gulf of California. And we have been working on the restoration of the Colorado delta for almost 10 years now, working with organizations from both sides of the border. We have been doing basic research to understand the issues and how can we restore the delta that is feasible, and then we have also been involved in active restoration and community work, monitoring, and more recently a lot on the water issues. We’ve created a water trust with some other organizations to purchase water and restore the flow in the Colorado River delta.

JW: Great, thank you. Brad, I’ll start with you again in the headwaters. What are the biggest challenges for water sustainability, for both humankind and natural habitat today in the Colorado River basin?

BU: When I think of sustainability issues with regard to the Colorado River, it really revolves around how much water is going to be in the river in the future, and are we using what we have now wisely. Like most Western states, roughly 75 percent of all the water here goes to agriculture. The remainder goes to municipal and other uses. The model projections for the future of the river show us anywhere from 10 to 20 percent reductions in flows mid-century, and obviously more possible by the year 2100. And if these come true, and there are many scientific reasons to believe that they will, it means we’re going to have to take a hard look at how we’re using water, and is there in fact any left to develop? Or maybe we’ve already overdeveloped what’s here. So it’s a challenge on almost any aspect of water management, from the critters needing water to live in, to humans, to agriculture, to even our new energy economy here in Colorado, which potentially, depending on how it evolves, might utilize significant amounts of water that might in fact not be here.

JW: And I’ll hand it to you, Osvel, in terms of water sustainability in the Colorado River basin, what do you think the biggest challenge is?

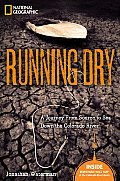

This infographic shows how much of the water is used for agriculture and how much goes toward industrial and municipal use. (Click for larger version.)OH: Well, I agree with Brad in that sense, and a lot of the [problem] came from the past and extended to the future. I mean, clearly the river was overallocated, and in different locations was given away to different cities and municipalities in the U.S. and in Mexico, too. The environment was not considered. And so into the future, we’re facing this challenge: How can we figure out a way to meet those allocations that have already been given away, and then at the same time how can we recover that water to retain environmental functions? So it’s quite hard. At the same time, I guess that this challenge and the stress into the system has opened a lot of dialogue that used to be closed between water managers, between agencies between countries, and also we have environmental organizations’ water managers. And so the discussion is more open, to try to collaborate and find solutions.

This infographic shows how much of the water is used for agriculture and how much goes toward industrial and municipal use. (Click for larger version.)OH: Well, I agree with Brad in that sense, and a lot of the [problem] came from the past and extended to the future. I mean, clearly the river was overallocated, and in different locations was given away to different cities and municipalities in the U.S. and in Mexico, too. The environment was not considered. And so into the future, we’re facing this challenge: How can we figure out a way to meet those allocations that have already been given away, and then at the same time how can we recover that water to retain environmental functions? So it’s quite hard. At the same time, I guess that this challenge and the stress into the system has opened a lot of dialogue that used to be closed between water managers, between agencies between countries, and also we have environmental organizations’ water managers. And so the discussion is more open, to try to collaborate and find solutions.

JW:When was the last time the river flowed into the sea, through the delta?

OH: The last event when there was water flowing from the Colorado River into the Gulf was around 1998-1999. There were big flow releases from the dams that reached into the Gulf of California. After that, there were some small releases that almost reached the upper Gulf, but not quite. Then there was a big earthquake on April 4 this year, causing quite a bit of damage in the irrigation system in Mexicali. So most of the Mexican allocation of water was directed into the river. So for a few days, there was water flowing into the river into the Gulf of California.

JW: I didn’t realiz

e that, I thought most of those systems were patched.

OH: Well, there was significant damage in the canal system, over 80,000 acres of land. So Mexico was not able to deal with the water delivery, so they would just open Morales dam. And for four days, there was continuous water from the Morales dam into the Gulf.

JW: The Morales dam — the diversion dam — is the only one owned by Mexico that brings water west toward Mexicali rather than toward the delta. So either of you — are we still in a drought today? The drought that started nearly a decade ago. I’ll toss that to you, Brad.

BU: Absolutely, yes. It’s the biggest drought in the historic record since 1906 or so, when we started keeping records in the Colorado River basin, and it’s really significantly a more pronounced drought than the next-nearest drought. You can look at droughts in a lot of different ways, but one way to look at it is in 10-year period flows, and this period of 10-year flows is 3 percent more than the next nearest period, if you will. Which doesn’t sound like a lot, but when you’re talking about flows over 10 years, it’s a huge amount of water. I think Lake Mead, for example, would be almost 50 feet higher if we were in the next-nearest drought, just to give you an idea. And Mead has dropped approximately 100 feet during this 10-year period.

JW: Can you clarify for people who might be in the Rockies that have seen snowfalls that are approaching average over the last few years, why the drought continues?

BU: Sure, and you’re right, I’m looking at a graph right now of precipitation over the last 10 years. And there were three years that were really bad at the beginning of the 2000s, 2001-2003. Almost all the years since then have been about average in terms of precipitation. But runoff has been significantly less. And we believe that these significantly high temperatures that we’ve been experiencing, especially over the last 10 years because of man’s emissions of greenhouse gases, have reduced the runoff in the river. What our research shows is a couple different things: We can develop relationships between temperature and runoff, and precipitation and runoff, and it appears that this system is very sensitive to increased temperatures. And as temperatures go up, and this is the reason for these predictions for 2050, even if you have the same amount of precipitation as we currently have for snow and rain, you get significantly less runoff as the American west heats up due to climate change.

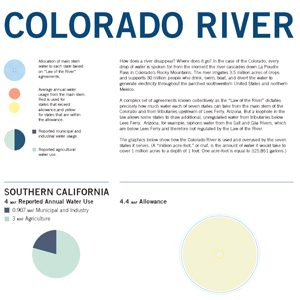

View the entire Colorado River basin and investigate water issues using this National Geographic map. (Click for larger version.) JW: That’s fascinating. So to recap that, even though skiers have been having a heyday the last three winters, at least in the Colorado Rockies, it doesn’t translate to water runoff because the temperatures are much warmer throughout the year.

View the entire Colorado River basin and investigate water issues using this National Geographic map. (Click for larger version.) JW: That’s fascinating. So to recap that, even though skiers have been having a heyday the last three winters, at least in the Colorado Rockies, it doesn’t translate to water runoff because the temperatures are much warmer throughout the year.

BU: That’s correct. And there’s another little piece to the puzzle here, brand new science — red snow that shows up in Colorado in the springtime these days. And it appears that all this dust, which is originating out of Arizona and Utah, is impacting runoff in very interesting ways. We think it might be leading to an average decrease of 5 percent runoff every year.

JW: And that’s because of the evaporation?

BU: Yes, the dust sits on top of the snow, and as the snow begins to melt in the springtime, the dust doesn’t sink down through the snow pack; it sits on top and absorbs more solar energy. Some of it evaporates, and because the snow melts sooner, the plants begin to use water sooner. So it’s a combination of two different forms of what scientists call evapo-transpiration, both evaporation and transpiration of water used by plants.

JW: Well, you both know a lot about the river, not only as scientists and researchers and through your careers, but Brad I know you were a boatman, and you both were kicking around in the basin for many years. I floated through Cataract Canyon and the Canyonlands National Park, Utah, for a few days again, and saw as many other people see, what seems to be an intact river mid-summer. From your experiences, is there any place where people can go to still see sections of the river, or even its tributaries that are relatively intact? Or is it really all a masquerade, are we looking at a river that’s a glimmer of its former self?

BU: I think when you ask that question, in some sense you lead us to the other tributaries that aren’t dammed and otherwise, because the dams obviously change the natural sequence of flow. And in the case of being in Cataract, there aren’t too many dams about you but there’s enough to change the flow. You’re still at the end of July, you probably are seeing some runoff from the snowpack, maybe not a lot. But rivers like the Dolores that only have one dam, might be a good place to see the river in its natural state, though I think some people would disagree with me, because that dam on the Dolores does change the hydrogravity pretty seriously.

The Yampa River is one of the last undammed rivers in the Colorado Basin.Photo courtesy of parks_traveler via FlickrJW: Or the Yampa, in early spring?

The Yampa River is one of the last undammed rivers in the Colorado Basin.Photo courtesy of parks_traveler via FlickrJW: Or the Yampa, in early spring?

BU: Yes, the Yampa has no dams on it. That’s a classic case, much better than the Dolores.

JW: So we have a few of those places left. Osvel, what is your favorite section of water in the Colorado River basin?

OH: I have to say, when you go in the upper basin, you feel it’s much more of a river than going into the lower basin or into the delta, and it’s fascinating to go there in the Dolores and Yampa and see the river behaving as a river. And as you walk down into the lower basin, I would say that the tributaries, it’s quite a good stretch. The Williams [is] quite a good patch. It’s below the Parker dam, and it’s used mostly for flood control, not for storage. So it still has pretty much a natural flow most of the year. So I would say in the lower basin the Williams River is the most natural stretch. But I have the say I enjoy parts in the Colorado Delta, like the Santa Clara. It’s very artificial in many ways; it’s basically maintained by agricultural return flows. But in the wetlands there, you feel the

wilderness.

JW: Tell me more — a lot of people who have seen that the river doesn’t flow through the delta have concluded that the delta is gone. So tell us more about the delta, and what’s alive there and why the Cienega [PDF] is a great hope.

OH: Yes, it’s a very interesting — there is no water flow in the river, but there are still very significant wetlands, and they are very important for wildlife. Every year in the winter, there are about 30,000 migratory water birds moving through the Colorado River in places like the Cienega, the Santa Clara, and the Rio Grande. And the funny thing is that these wetlands were basically maintained by agricultural return flows and seepage from canals. Just a small part of them are maintained by dedicated water, so that is one of the things that we’re trying to change. There are still about 60,000 to 80,000 acres of wetlands in the delta, mostly marshes and some shallow pools, and very important mudflats. But also there are still significant patches of cottonwood and willows, so again they don’t have this allocated water, but they still have very important environmental values.

JW: So to put that in context — I hear a large note of hope and logically a good reason for hope — how much of the delta is missing, compared to what we would have seen if we traveled there a century ago?

OH: Oh, probably about 80 percent is missing, and the remaining 20 percent is not the same quality as what it used to be. So yes, certainly it has been a very large loss. This area including the whole Mexicali valley, and you can extend that farther into Mexico, used to be the Colorado River delta. We’re talking about 500,000 acres of mixed wetlands, riparian forests, marshes, and into the estuary and upper Gulf of California, though now that has been mostly converted to agriculture. But there are still some patches in good shape.

JW: So are there sufficient resources being brought to bear on issues on the river, whether it’s habitat that you’re talking about Osvel, or even climate change issues, Brad?

BU: Good question, I think not in the realm of science. I think people would like to bring more resources to bear, there’s a $2 million dollar study underway that’s trying to look at future supply and demand on the system, and it’s a big enough system that $2 million isn’t nearly enough. By comparison, the Australians did a study on their effective analogue, the Murray-Darling basin, and they spent $10 million on that study to get the kind of information that we’re trying to get out of $2 million. I think there are a lot of people that are interested in this and a lot of concern about the future from many different perspectives, including water providers and users, but we haven’t figured out how to get the necessary resources directed at the river.

JW: On the eastern seaboard on this country, there’s a great deal of rain. There’s more than 40 inches of rainfall a year there, and in the west we have half that, and down where Osvel is, maybe 2 inches of rain a year. So I wonder if it’s not a complete misunderstanding of climate and the lack of water to begin with that people can’t bring for their resources to bear.

BU: It’s clearly partly that, Jon.

OH: I agree, there is not enough understanding, and I agree that there has not been enough resources to address the issue, from the science perspective, getting all the information that we need to make the best decisions, I don’t think we are there yet, and also for the policy work that is needed in order to bring together different perspectives in the basin, that needs a lot of resources and time and commitment from the different parties, and I don’t think we are there yet.

JW: Yeah, rather than the $2 million or $10 million that is being used in Australia, perhaps we need three times that much to begin a study so we can figure out where to begin. So that brings me to the question of how do we make people aware? Whether they’re users of the river here in the west, or whether they’re policy-makers in D.C. What can we do to call people’s attention to what I often think of as a potential train wreck?

BU: What it really takes is an extreme event. And I really hate to say this, but it’s true. It takes a [Hurricane] Katrina, or it takes an enormous drought. We may be getting close to that in terms of where Lake Mead is and where it’s headed. It’s 90 percent of the water supply for Las Vegas, and if Lake Mead drops another 25 feet the entity that runs the river, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, is going to have to implement shortages to some of the users in the lower basin, the first time ever that will occur. So I’m a firm believer in crisis as being a good driver in change and awareness.

JW: If it’s not too late, I guess.

BU: Yeah, if it’s not too late. There are a lot of people who are trying to do the educational component on this river, and there’s a subset of people who absolutely pay attention and know the risk, and then there are a whole bunch more of American people in the West who are totally oblivious to where their water comes from.

JW: Alright Osvel, your take on that crisis model?

OH: Well yes, crisis absolutely is a driver — and it’s already working. For the first time, Mexico perceived that there could be a shortage. Since 1944, with the International Water Treaty, the U.S. has always delivered the amount of water they have to deliver to Mexico. But now, in the future, there is this very real risk that the U.S. could deliver less water. So it has certainly called attention to officials in Mexico City, who now are more attentive to the situation and more willing to have a dialogue with U.S. counterparts and taking into consideration the point of view the managers, the water users from the Colorado Delta-Mexicali region.

JW: So our audience can understand restoring whole flows to the delta, could you talk about that briefly, how much money it would take and what it would take to see the type of restoration that could bring us back — not to a completely restored delta — but a delta that at least has some natural function left to it.

OH: Right, well that’s one of the bases of the restoration work we’re doing for the delta, not just the planting of native trees, but restoring flows. And that has two components: one is that the base flow, which we think does not need to be a large amount — we’re talking something between 16,000 to 18,00 acre feet a year, we’re still refining that number. And we’re considering that we can get that water from purchasing water

rights from the Mexicali valley. So that’s one of the ideas. The other component is a post-flow. So if we only have a base flow, the riparian system does not work as it should. It needs this flowing every certain amount of year, even if they are only for two or three months, but in a larger flow, maybe 700 cfs [cubic feet per second]. For that, that aspect needs to have international collaboration, because it needs release from the dams that go all the way to the delta. And that’s part of what’s happening now with international negotiations between the United States and Mexico, trying to figure out if we can make that happen.

In terms of how much it will require, in terms of the base flow, it’s a very good question because water prices are changing and we’re still not sure about the total amount of water. We’re talking about several million dollars, at least.

JW: And is that just Mexico’s share?

OH: Yes, and that’s for the base flow, and we’re thinking of getting the water from the Mexicali valley.

BU: If I can, let me just get that in context. 100,000 acre-feet is less than 1 percent of the annual flow of the river. It’s something that we should be able to figure out how to do. Many people north of the border think this is solely a Mexican problem — that they have their water down there and we have our water up here. I tend to look at it more inclusively and think that this is a joint problem between the two nations, and we should jointly figure out how to solve it. And some people will think this is blasphemous of me, but I think the U.S. should supply some of this water.

Colorado River water is sent east under the Rockies through 12 different tunnels to supply the growing cities surrounding Denver.Photo courtesy of Jonathan WatermanJW: We talk about water grabs even from the headwaters that the U.S. has to deal with and the upper and lower basin have to deal with; we have performed a water grab essentially, on one of the most important features of the river. And I think as Brad says, it behooves us to look for a solution to bring water back to the delta.

Colorado River water is sent east under the Rockies through 12 different tunnels to supply the growing cities surrounding Denver.Photo courtesy of Jonathan WatermanJW: We talk about water grabs even from the headwaters that the U.S. has to deal with and the upper and lower basin have to deal with; we have performed a water grab essentially, on one of the most important features of the river. And I think as Brad says, it behooves us to look for a solution to bring water back to the delta.

BU: It’s really a tiny amount of water that is needed, and it seems to me through savvy water management, we could come up with this water.

JW: Well, if you guys could choose between limiting greenhouse gasses, curbing population growth in the basin, readdressing issues of allocation, or farm water — remanaging the use of agricultural water — which would you take as the most important cure for the water’s predicted demise?

BU: All of the above!

OH: Yes, all of the above absolutely. I don’t think we can solve the river issues picking just one issue. It’s really a function of different things. Certainly managing and looking differently at the management of agricultural water would probably yield results sooner, so I guess it’s like a first step you can go to and have more water available to work in a direction. But if you don’t tackle the issue of population in the basin and the over-allocation problem and the system-wide management and the issue of climate change, then we will be in the same spot in a few years. So I guess all of the above.

BU: It’s easy to tag climate change as the big boogeyman of the 21st century. If you do that, I think you overlook an enormous amount of stresses that the world and the American Southwest are facing. And I think you put your hand on all of them when you posed that question, and they’re all really important. This century is going to be unlike any other, and it’s not just climate change. Climate change is an additional stressor to all these other ones. And yes, there is a lot going on right now that we need to pay attention to.

JW: To wrap this up, can either of you make suggestion as to what readers at Grist.org can do in terms of their own daily lives for issues of water sustainability, whether it be in Oklahoma or Seattle or here in the drying southwest?

OH: Well, the first thing is to just get informed. Get informed about your water sources and your basin, and the environmental component of the water we use, and how it affects the environment in your basin and the issues. And probably there are organizations already working on those issues. So getting informed is certainly the first thing you need to do to participate better.

BU: I think that’s absolutely true. Too many people think that their water comes “out of the tap”, and the truth is that it comes out of a river somewhere, or a groundwater basin somewhere. Understanding the impacts of the local use on the source of water is pretty important. That falls under getting informed. On a very local sort of home-issue, over the last five years I’ve begun to keep track of the water usage in my house, just looking at the bill, and also my electricity use. And it’s really interesting to see what you can do in terms of conservation with just a little bit of effort, it doesn’t take much. My electrical use is down about 30 percent, just by doing savvy things around my house, and your water use can be pretty similar if you’re savvy about it. People frequently over-water outside, and they take long showers that they don’t need to, and there are tons of ways to save water.

JW: I do the same thing at my home, and I like to look toward water products. The food that I eat and where it comes from is overlooked by a huge portion of consumers, and the things we do as consumers of water; things like beef or cotton or all the dairy productions, all which come from the Colorado River Basin consume an enormous amount of water, whether it’s through giving this water to agriculture, or the water we’re using for alfalfa throughout the basin.