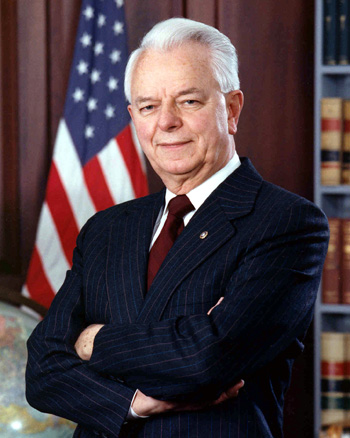

Sen. Robert Byrd (D-W.Va.), who died early this morning at the age of 92, fought for most of his legendary career to keep coal mining at the center of West Virginia’s economy. But in the last few months of his life, he hinted at a remarkable change of heart, speaking out on the damage coal causes in his state and the need for change. Ultimately, his demise hurts the odds the Senate will pass a climate bill this year, since his successor is likely to be a more consistent defender of coal-mining companies.

Sen. Robert Byrd (D-W.Va.), who died early this morning at the age of 92, fought for most of his legendary career to keep coal mining at the center of West Virginia’s economy. But in the last few months of his life, he hinted at a remarkable change of heart, speaking out on the damage coal causes in his state and the need for change. Ultimately, his demise hurts the odds the Senate will pass a climate bill this year, since his successor is likely to be a more consistent defender of coal-mining companies.

Let’s unpack that.

Defender of both coal companies and miners’ rights

Politicians don’t rise in West Virginia without showing deference to the coal industry, but Byrd went further than that, keeping coal interests at the heart of his work during his record 57-year congressional career. The dogged Charleston Gazette reporter Ken Ward Jr. sums up his career this way:

The nephew and son-in-law of coal miners, Sen. Byrd was a longtime champion of miners and of the industry, working for tougher mine safety legislation and to moderate environmental laws and rules to protect coal workers.

Among environmentalists, Sen. Byrd developed a bad reputation. First, he championed a 1997 Senate resolution aimed at blocking action on greenhouse gas emissions. And he led efforts by West Virginia’s congressional delegation to overturn Judge Haden’s 1999 ruling to limit mountaintop removal, at one point ridiculing environmental activists, saying:

These head-in-the-cloud individuals peddle dreams of an idyllic life among old-growth trees, but they seem ignorant of the fact that, without the mines, jobs will disappear, tables will go bare, schools will not have the revenue to teach our children, towns will not have the income to provide even basic services.

A change of heart?

Over the last seven months, Byrd offered hints that his positions on coal and climate change had shifted. Again, from Ken Ward:

About a year ago, Sen. Byrd sent his staff into the coalfields, on a fact-finding mission, and last December came out with his major statement, urging the coal industry to “Embrace the Future.” Among his most important points? That change was coming to the West Virginia coalfields, regardless of what happens with cap-and-trade legislation and mountaintop removal restrictions.

In April, when 29 miners died in a mine run by Massey Energy, a company with a history of excessive safety violations, Byrd ripped the company and the mining industry for putting profits ahead of the health of its workers and the people of West Virginia. In an op-ed in the Charleston Daily Mail, he wrote:

A single miner’s life is certainly worth the expense and effort required to enhance safety. West Virginia has some of the highest quality coal in the world, and mining it should be considered a privilege, not a right. Any company that establishes a pattern of negligence resulting in injuries and death should be replaced by a company that conducts business more responsibly. No doubt many energy companies are keen for a chance to produce West Virginia coal.

The industry of coal must also respect the land that yields the coal, as well as the people who live on the land. If the process of mining destroys nearby wells and foundations, if blasting and digging and relocating streams unearths harmful elements and releases them into the environment causing illness and death, that process should be halted and the resulting hazards to the community abated.

Byrd slammed the Waxman-Markey climate and energy bill that passed the House last summer, but in the months following, he sounded more open to a Senate climate bill — provided it included support for “clean coal” and carbon capture and sequestration. “To deny the mounting science of climate change is to stick our heads in the sand and say ‘deal me out.’ West Virginia would be much smarter to stay at the table,” he wrote in December. As recently as last month, E&E Daily considered Byrd to be a fence-sitter on climate legislation.

Get ready for a new shill

Ultimately, though, Byrd didn’t do much to act on his new perspective. And his successor isn’t likely to be much help, since he or she will be appointed by West Virginia Gov. Joe Manchin (D), who declared coal the official state rock and seems to oppose any restrictions on climate pollution from coal. His pick will be a Democrat but not one who’s likely to support a climate bill.

It’s not yet clear whether Manchin’s appointment will serve through 2012, or merely until the end of this year. If there’s a special election this year, Republicans have a good chance of picking up the seat.

“I don’t feel very confident that we’ll get the kind of person that we need,” Jim Sconyers, chairman of the West Virginia chapter of the Sierra Club, told Greenwire. “Given Joe Manchin’s position — he’s a tool of the coal industry — no question about that.”

Byrd’s death also spells trouble for the financial reform bill, putting Democrats one vote short of overcoming a Republican filibuster. If the Senate takes extra time to resolve this (or fails to resolve it), that too makes climate legislation this year even less likely.