Charlotte is car-loving NASCAR country, a vast suburbia of cul-de-sacs and strip malls. Yet its new light rail line is a national model for success, outstripping ridership projections and inspiring millions of dollars in high-density development. How did sensible transportation planning come to sprawlburbia? Not by appealing for “sustainability,” that’s for sure. In the end, the winning pitch that sold voters on light rail was none other than Charlotte’s love of growth. The development it lured — several thousand condos and apartments, dozens of new restaurants and stores, and roughly half a billion dollars in private investment — showed skeptics that light rail is more than just transportation. The city created transit-oriented zoning districts and station area plans, allowing for increased density along the rail line.

Other players in this success story included a mayor who took leadership, a restored vintage streetcar, and plain old lucky timing: A decade-long real estate bubble fed the transit-related development, not bursting until after the Lynx light rail debuted in November 2007, followed quickly by 2008’s record-breaking high gas prices.

Today, with the North Carolina textile industry long dead and Charlotte’s famed banks weakened, the city’s leaders look to position it as an emerging “green” metropolis. Its transit triumph makes for compelling evidence.

The Beginning

It took 20 years for Charlotte’s light rail line to become an overnight success. Back in the 1980s, many of top leaders of both political parties knew regional transit was needed. But any suggestions for taxes to fund it were DOA at the rural-dominated state legislature, whose permission was needed. Two barriers had to fall: Convincing a conservative electorate that transit wasn’t a frill, and finding millions to build it.

Enter Charlotte Trolley, a volunteer group of rail buffs and enlightened developers who decided to restore an antique trolley car (found being used as a rental home outside Charlotte) and run it on an unused railbed near downtown. In 1996, after eight years of fundraisers, Charlotte Trolley launched a 1.8-mile ride, drawing throngs who loved the taste of old-fashioned streetcar travel. Keen-eyed developers built rail-oriented mixed-use projects, betting light rail service would follow.

Also in 1996, six months into his first mayoral term, conservative Republican Pat McCrory put transit atop his agenda. He lobbied relentlessly — not about carbon footprints or global warming — but about transit as economic development. The legislature finally OK’d a half-cent sales tax for transit, if voters approved. In 1998 they did.

The Dreamers

UNC CharlotteDan Morrill.

For years, history professor and preservationist Dan Morrill dreamed of returning streetcar service to the city. In 1987 he learned that Charlotte’s last operating streetcar — put out to pasture, literally, in 1938 — had turned up in the countryside. He and other volunteers found money, cajoled the city, and pitched the trolley as a precursor to light rail. When it began running in 1996 it proved wildly popular, offering what Morrill has called “the romantic, nostalgic, historic delight of the trolley.” It was a ride into the past, and a glimpse into the future. “To the extent that I have made the world a better place,” Morrill said once, “the trolley would be very, very, very high on the list.” Sadly, federal safety rules sidelined Car 85 when the Lynx line opened.

A hometown boy, developer Tony Pressley saw other cities restoring aging industrial areas and thought Charlotte could do the same along the unused rail line being eyed for trolley service. He successfully renovated an old textile mill into restaurants, shops, and condos. He pushed for state legislation easing liability roadblocks to brownfield redevelopment. His profits and vision emboldened other developers. Further, Pressley understood that people’s affection for the antique trolley would translate into public support for light rail.

James Willamor / flickrPat McCrory.

Elected mayor in 1995 at age 39, Pat McCrory understood two important concepts: Building roads alone won’t solve congestion, and high-density growth would be necessary for transit to succeed. In 1998 he led lobbying that convinced state legislators to put to the voters a half-cent sales tax for transit. It passed with 58 percent of the vote. McCrory also led the effort to change old suburban-style development patterns in order to encourage walkable, mixed-use development near transit stations. It’s vital to integrate the plans, he says: “Don’t look at transit in isolation.” Right-wingers in McCrory’s party fumed at his transit support, calling him a RINO (Republican in Name Only) or a socialist. Nevertheless, he won seven mayoral terms, stepping down in 2009. (See our Q&A with Pat McCrory about the Lynx project.)

Sound TransitRon Tober.

Ron Tober was a seasoned transit executive who had worked in Cleveland, Miami, and Boston. Hired in Charlotte in 1999, he understood the federal transit funding labyrinth, technical details, and — significantly — how transit and land use plans must be linked. But as construction costs soared and delays accumulated, Tober became a lightning rod for public anger. Anti-transit activists put a measure on the ballot in 2007 to scrap the transit tax. In August that year, Tober announced his retirement; three months later, voters resoundingly upheld the tax. Later that month the Lynx line opened successfully. Tober is now deputy CEO for Sound Transit in Seattle.

The Money

The final tally to build the 9.6-mile light rail line was $473 million: $107 million from state money, $213 million from federal funds, and the rest in local money. (Original estimates were $227 million.) Also, Charlotte city government spent $60 million for pedestrian and intersection improvements near transit stations, including a 3-mile sidewalk and bike path beside the railbed.

The county’s half-cent transit tax makes up about half the transit agency’s revenue — and in a county with 11-12 percent unemployment it’s bringing in 15 percent less than the year before. Last year the tax produced $62 million instead of the projected $76 million. Fares will rise July 1, and a planned 11-mile extension will likely be stalled until 2020 or later. Other plans for commuter rail, a streetcar, and additional light rail lines are back-burnered unless a federal grant-fairy godmother swoops in.

The Outcome

Development in the Lynx station areas includes 45 projects totaling more than $247 million as of April 2010, including 100 affordable housing units out of a total of some 1,400 new units, and 700,000 square feet of office and retail space.

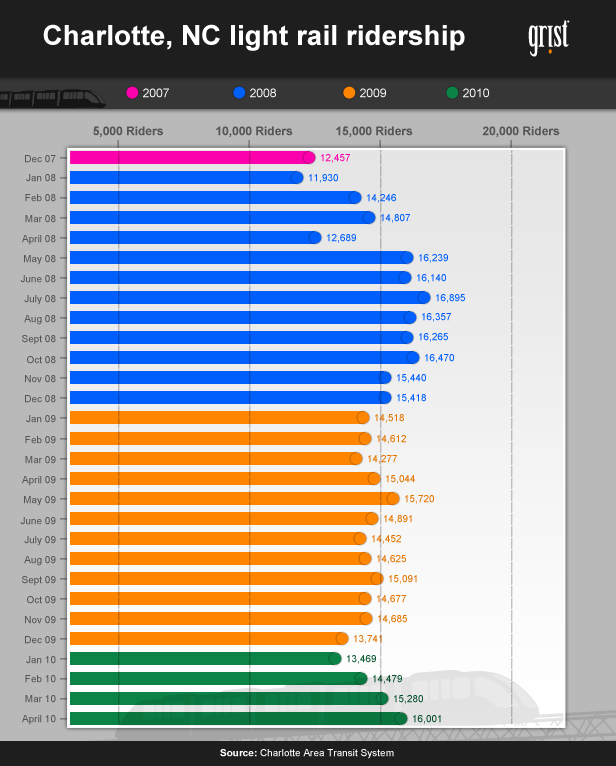

And the people have turned out in droves. Before Lynx opened, the projection was 9,100 average weekday ridership its first year. But in the first month of operation alone, that estimate turned out to be 3,000 people too low. The graph below shows average weekday ridership for each month since train started running.

The Copycats

The recession officially began in December 2007 — a month after Charlotte’s Lynx opened. McCrory still gets invited to other mid-sized Sun Belt cities such as Tampa and Nashville to talk about Charlotte’s pragmatic approach. And the city has drawn plenty of visiting planners and developers. But nationally, says Ron Tober, “There’s not much copying going on. There’s not much new starting.” He points to Tampa as another city following Charlotte’s model, at least in part. Tampa officials have visited at least twice and have a 1-cent sales tax provision on the ballot in November for transit, plus a light-rail champion in Mayor Pam Iorio.

McCrory lists the four things other cities should emulate about Charlotte’s efforts: Build a bipartisan team of business and community activists, evangelize the long-term vision of transit, create a regional governance structure for transit, and build rail lines where they’re needed, rather than where they’re politically popular.