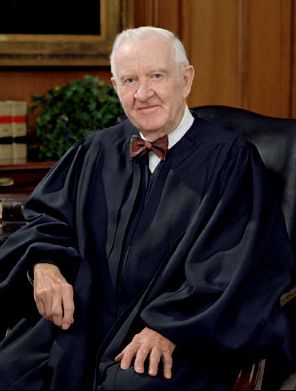

Following last Friday’s announcement that Justice John Paul Stevens will retire from the Supreme Court at the end of this term, President Obama hailed the Court’s most senior Justice as “an impartial guardian of the law.” This description is certainly accurate, and is perhaps best illustrated by Justice Stevens’ numerous rulings in environmental cases.

First, it is worth remembering that Justice Stevens came to the Court in 1975, at the dawn of the modern environmental movement and amid a heady time for environmentalists in the courts. Just a few years earlier, in a dissent from the landmark case Sierra Club v. Morton (1972), Stevens’ predecessor, Justice William O. Douglas, had famously argued that natural resources such as trees and rivers should have “standing,” positing that if corporations are permitted to represent their interests in court then so too should other inanimate objects. Meanwhile, in cases of statutory interpretation, judges on the powerful U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit had developed a number of doctrines that allowed them to aggressively second-guess agency decision-making in order to realize the broad and ambitious goals of environmental statutes. These developments invigorated environmentalists, but they also introduced a sense of permissive creativity into a rapidly growing body of environmental law, and exposed judges who made pro-environmental rulings to allegations of judicial activism.

Justice Stevens, by contrast, firmly rejected the idea that environmentalism was some sort of transcendental force that gave judges special powers to enforce broad statutory goals on their own and overrule regulatory agencies. Most famously, in Chevron v. NRDC (1984), he wrote a majority opinion for the Court that sternly rebuked the D.C. Circuit for substituting its judgment for that of the Reagan EPA, which had sought to give industry more flexibility in meeting their Clean Air Act obligations. Though a bitter defeat for environmentalists, Chevron, which holds that judges must defer to agencies when they make a reasonable judgment about an ambiguous law, is rightly hailed today as a landmark of both administrative law and judicial restraint.

Those same principles — deference to the plain language of statutes and concern about judicial restraint — are the hallmarks of Justice Stevens’ other landmark environmental rulings, which have rightly earned Stevens the enduring gratitude of the environmental world. In Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter Of Communities For A Great Oregon (1995), Justice Stevens wrote for a six -Justice majority in reinstating the portion of the Endangered Species Act that protects endangered species’ habitats, which had been struck down by the D.C. Circuit (which by then had been taken over by Reagan and Bush appointees). This time, Justice Stevens’ opinion corrected the D.C. Circuit’s narrow reading of an environmental statute by finding that the language and intent of the Endangered Species Act was clear in forbidding changes to habitats that will harm endangered species.

In 2002, Justice Stevens wrote another rule-of-law environmental opinion in Sierra Preservation Council v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, a “takings” case that followed a 15-year period during which the Court’s conservatives, led by Justice Scalia, had been remarkably inventive in trying to transform the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment into a barrier to environmental laws. Rejecting this bending of the Constitution’s meaning, Justice Stevens garnered another six-Justice majority in upholding land-use protections put in place to save Lake Tahoe. The ruling returned the Takings Clause to its more limited role as a guard for securing compensation for landowners when the government exercises its power of eminent domain.

Finally, and perhaps most famously, in Massachusetts v. EPA (2007), Justice Stevens relied on Chevron and the unambiguously broad terms of the Clean Air Act in holding that the EPA may regulate greenhouse gas pollution using its existing authority under the Act. This ruling has allowed the Obama Administration to aggressively combat global warming without waiting for further action by Congress, setting into motion a chain of regulatory actions that has led to the nation’s very first nationwide auto emissions standards aimed at greenhouse gases, and may soon lead to the nation’s first restrictions on CO2 emissions from power plants.

Justice Stevens should be remembered as a great justice in environmental cases, not because he bent the law to favor environmental outcomes, but rather because he insisted that the law itself, which dictates environmental outcomes in many cases, be followed.