Tim SimpsonTechnology will not teach this puppy how to behave. Bad adorable puppy!

On Friday, journalist John Fleck made a great point, comparing coverage of two new pieces in Science. One is about the latest potential climate disaster: methane venting from the seafloor in the Arctic. The second is about a promising new climate solution: using behavioral science to influence energy use. Not surprisingly, the disaster got tons of coverage. The solution got none. This is entirely typical. As Fleck says, “The problem space gets more attention than the solution space.”

So let’s do something about that! Let’s take a look at this under-covered solutions piece.

I’ve been saying over and over lately that changing behavior is as important as changing technology. Yet behavioral science is neglected relative to technology R&D. Everyone understands the importance of scaling up wind, solar, and geothermal power, but when was the last time you heard a policymaker or pundit talk about scaling up the practical application of knowledge about how human beings think, interact, and make decisions?

In their paper, “Behavior and Energy Policy,” Hunt Allcott of MIT and Sendhil Mullainathan of Harvard argue for taking such knowledge seriously:

Just as we use R&D to develop “hard science” into useful technological solutions, a similar process can be used to develop basic behavioral science into large-scale business and policy innovations. … What has been missing is a concerted effort by researchers, policy-makers, and businesses to do the “engineering” work of translating behavioral science insights into scaled interventions, moving continuously from the laboratory to the field to practice. It appears that such an effort would have high economic returns.

That last sentence is a bit modest given the numbers Allcott and Mullainathan marshal. They’ve taken a close look at the results so far from behavioral programs in the field and the results are fairly astonishing.

Start with the most basic test: how much does it cost for a given climate solution to eliminate (abate) a metric ton of CO2 emissions? With plug-in hybrid vehicles, that ton costs around $12. With wind power, it’s $20. With carbon capture and storage at coal-fired power plants, it’s $44.

How much does that same ton of CO2 abatement cost using these behavioral programs? -$165. No, that’s not a typo. It’s a negative sign. As in: $165 worth of profit per ton of carbon pollution reduced. If similar programs were expanded nationwide, Allcott and Mullainathan estimate a net value — savings minus costs — of $2,220,000,000 a year. Of course much research and testing remains to be done before it’s clear whether these programs perform equally well at scale, but as a first approximation, that’s not too shabby.

Incidentally, some of the data comes from programs run by Opower, a Virginia-based company that works with utilities to apply behavioral science in a way that delivers energy efficiency. I’ve mentioned them before, and as it happens, President Obama visited them on Friday. “You can see the future in this company,” he said. (Why isn’t that a bigger story?)

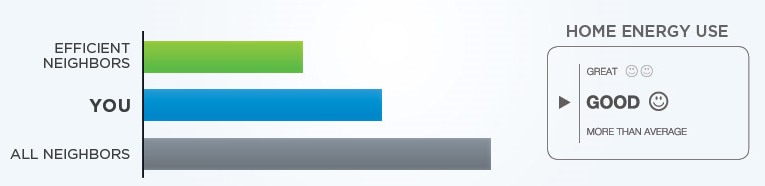

Here’s Opower’s solution to reducing energy use:

High-tech, huh? Put a chart like that on utility bills and you get about a 2 percent average drop in energy use. And it hardly costs the utilities anything! They already have the data. It’s just a different way of presenting information, informed by good social science. As social psychologist (and Opower adviser) Robert Cialdini said when I talked with him, there’s more than 50 years of scientific research on this stuff. It just hasn’t been communicated broadly or translated into policy.

Time to start translating! Allcott and Mullainathan offer three policy recommendations.

First, governments can provide funding for potentially high-impact behavioral programs as part of their broader support for energy innovation. A bill under consideration in the U.S. House of Representatives, HR 3247, would establish a program at the Department of Energy to understand behavioral factors that influence energy conservation and speed the adoption of promising initiatives.

Side note: that bill, HR 3247, was sponsored by Washington’s own Rep. Brian Baird (D). He got it passed out of House Science and Technology Committee but right-wingers, led by Glenn Beck, pitched a fit, saying it was government mind control. The teabaggers created such a distraction that the bill was subsequently withdrawn. I’m going to chat with Baird about the episode later this week.

Moving on:

Second, through market incentives, policy-makers can encourage — or fail to encourage — private-sector firms to generate and utilize behavioral innovations that “nudge” consumers to make better choices. Historically, economists and policy-makers have focused on how regulation affects relative prices … In practice, however, firms interact with consumers in many ways in addition to pricing.

And finally:

Third, government agencies often provide independent information disclosure, such as vehicle and appliance energy-efficiency ratings. This helps catalyze private-sector innovation by allowing firms to credibly convey the financial value of energy efficiency to consumers. The effect of information on choices, however, depends critically on how the information is conveyed, and government agencies should carefully consider behavioral factors in the disclosures they control.

For example: the EPA rates fuel efficiency according to miles per gallon (MPG), which turns out to be misleading in all sorts of ways. (See: “The MPG Illusion.”) If it instead reported based on gallons per mile (GPM), it would better inform consumers about the real value of efficiency and thereby lead to better choices. Most importantly, it would cost EPA virtually nothing. It’s just a matter of applying knowledge about how people tick.

——

Nerdy addendum

When considering interventions, policy-makers usually focus on price, or information about prices. As Allcott and Mullainathan note, this focus derives from the the rational choice theory of traditional economics. (I’ve harped on that lately too — here, here, here, and here.)

Problem is, behavioral psychology and neuroscience have demonstrated that the rational-choice ideal no longer holds water. John M. Gowdy of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, in “Behavioral Economics and Climate Change Policy,” puts it this way:

The axioms of consumer choice — the starting point of traditional economic theory — have been re-cast as testable hypotheses and these assumptions have come up short as defendable scientific characterizations of human behavior. It is no longer tenable for economists to claim that the self-regarding, rational actor model offers a satisfactory description of human decision making. Nor do humans consistently act “as if” they obey the laws of rational choice theory …

… Ironically, the rational actor model seems to be most appropriate for animals with limited cognitive ability and perhaps humans making the simplest kinds of choices. For the most important decisions humans make, culture, institutions, and give-and-take interactions are critical and should be central to any behavioral model.

Much of behavioral economics has been devoted to debunking rational choice theory, but a positive alternative is just beginning to emerge, a kind of unified theory of human behavior that harmonizes research from economics, sociology, anthropology, and psychology. Read Gowdy’s fascinating paper for more on that.

——

Some previous posts that touch on all this stuff:

- Making buildings more efficient: looking beyond price

- Making buildings more efficient: It helps to understand human behavior

- Why Bill Gates is wrong

- Never mind what people believe — how can we change what they do? A chat with Robert Cialdini