I tried, unsuccessfully, to learn if anyone from Bhopal, India, would be speaking at the climate summit in Copenhagen.

It seems unlikely, but the delegates gathering in Copenhagen need to hear what only someone from Bhopal can properly tell them. They need to know what it was like 25 years ago this week, when a cloud of poison gas leaked from a pesticide plant in the middle of the night and drifted over the Bhopal slums. Thousands died; it was the worst industrial disaster in history and it holds lessons that are essential to the proceedings on climate change about to start in Copenhagen.

To those who came of age after Bhopal, here are the awful details:

* The sirens started at the Union Carbide plant at 12:50 AM on December 3, 1984. The public alarm was turned off after a minute. A second alarm, heard only inside the plant, continued to warn UC workers. The two alarms had originally been on a single switch, making it impossible to turn off one without deactivating the other. But frequent leaks caused the alarms to sound so often that the company became concerned about its reputation. They took decisive action in 1982: they decoupled the alarms.

* At 1:15, someone told the police that there was a gas leak in the northern part of the city. The police called Union Carbide, but were told that the UC plant was secure. Officials searched frantically for the source of the leak for the next hour, calling the UC repeatedly. Each time, the company insisted they were unaware of any problems.

* At 1:15, someone told the police that there was a gas leak in the northern part of the city. The police called Union Carbide, but were told that the UC plant was secure. Officials searched frantically for the source of the leak for the next hour, calling the UC repeatedly. Each time, the company insisted they were unaware of any problems.

* At 2:00 AM the nearly-empty tank stopped leaking. Fifteen minutes later, UC restarted the public warning siren. An engineer from the company contacted the police. The leak that – up until that moment – the company had denied any knowledge of, was, he reported “plugged.”

* Officials from Union Carbide’s U.S. headquarters maintained that the leak was an act of sabotage by a disgruntled former employee.

There’s something else the delegates should see: advertisements, created decades apart, one by Union Carbide and one by the coal industry.

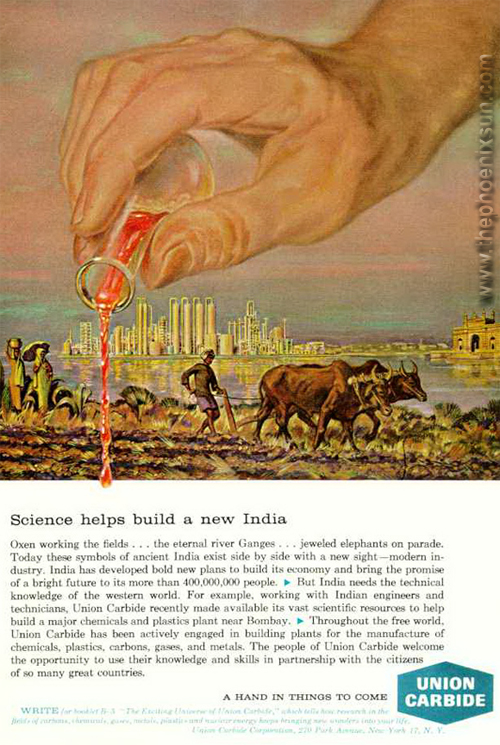

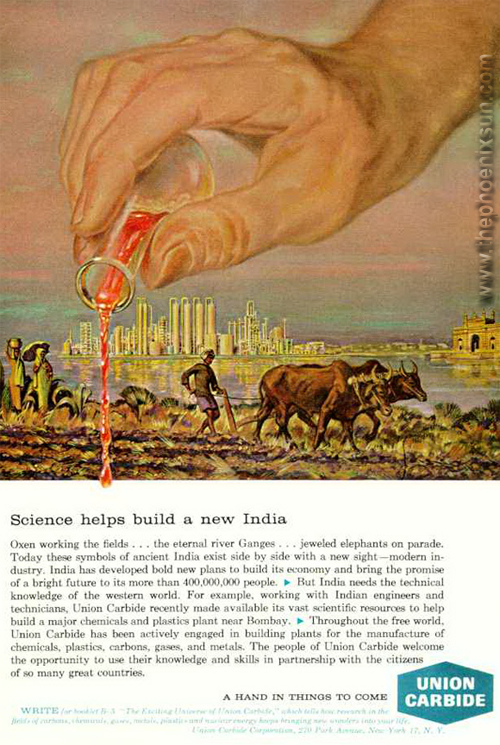

In the UC ad from the 1960s, a giant, god-like Caucasian hand from the sky pours an elixir from a lab flask onto a “symbol of ancient India … oxen working the field” with a dark-skinned Indian peasant behind a wooden plow. In the background just across a river, the UC Bhopal plant rises gleaming and white.

Below the picture a headline provides the take-home message: “Science helps build a new India.” If Science is a god, as the picture implies, its manifestation here on Earth was Union Carbide.

“Working with Indian engineers and technicians,” states the ad, “Union Carbide recently made available its vast scientific resources to help build a major chemicals and plastic plant near Bombay.”

If any doubts still lingered about UC being the very incarnation of Science, the tag line at the bottom of the page was designed to clear things up. Placed next to the Union Carbide logo, it reads: “A HAND IN THINGS TO COME.”

The messaging around “clean coal” has been updated for the new millennium, but most of the same elements from the UC ad are present.

In place of a hand, the billboard at left below, sponsored by the coal industry, features a giant light bulb with a beautiful nimbus of other-worldly (and environmentally friendly) green light. The word “COAL” is also green-tinged on the sign. At the bottom of the billboard, the themes of Science and modernity are combined with the words: “CLEAN & GREEN WITH NEW TECHNOLOGIES.”

Coal, of course, is neither clean nor green. Burning coal to generate electricity is the single largest source of CO2 emissions, which, in turn, is the primary greenhouse gas driving climate change.

Coal, of course, is neither clean nor green. Burning coal to generate electricity is the single largest source of CO2 emissions, which, in turn, is the primary greenhouse gas driving climate change.

But, the ad seems to promise, coal is no longer a cause of climate change, thanks to new technologies. In fact, these technologies do not yet exist. They may never work at a scale that makes coal a “clean and green” fuel.

And if the most frequently mentioned technology, carbon capture and sequestration (CCS), is somehow made practical, it could create hundreds of potential Bhopals. The idea behind CCS is to capture millions of tons of CO2 from burning coal and pump them deep into the earth where, in theory, they won’t leak out.

The same companies that until recently insisted that human-caused climate change is a hoax, now ask us to trust them with a technology they say exists, but doesn’t.

It’s helpful to look at climate change itself is an industrial disaster, albeit one that’s happening over a longer period of time than Bhopal. The economic might and political influence of Union Carbide caused the thousands of deaths in India. In the wake of Bhopal, people in the United States began to wonder what was being made in the chemical plants near them. Should they be concerned? The chemical industry reacted swiftly.

Less than a year after Bhopal, the chemical industry trade group bragged in an internal report that they had fought off new regulations and right-to-know laws in nearly forty states.

“We have,” the author of the report boasted, “retained our trade secret protection rights and successfully avoided costly requirements for unique labeling, environmental emission monitoring and independent risk management audits.”

Avoiding regulation, blocking public access to information, denying culpability for disasters they’ve caused, sowing doubt where scientific consensus exists – these are the strategies used by reckless industries from tobacco to chemical manufacturing to energy production.

Some of the same entities are already at Copenhagen arguing for minimal action and maximum delay. It’s too bad organizers chose Copenhagen for the summit. It’s far too lovely. Delegates should have met in Bhopal at the abandoned chemical plant that caused the worst industrial disaster in history. The worst, that is, until now.

A longer version of this piece was originally posted on thephoenixsun.com.

Spread the news on what the føck is going on in Copenhagen with friends via email, Facebook, Twitter, or smoke signals.