Greg Nickels. It was a dark, dreary, drizzly November morning in Seattle when I visited Greg Nickels, the city’s lame-duck mayor and an influential national voice on the need for climate action over the last decade. Outside the LEED Gold-certified City Hall, a gray murk hung in the air, nearly obscuring Elliott Bay five blocks away.

Greg Nickels. It was a dark, dreary, drizzly November morning in Seattle when I visited Greg Nickels, the city’s lame-duck mayor and an influential national voice on the need for climate action over the last decade. Outside the LEED Gold-certified City Hall, a gray murk hung in the air, nearly obscuring Elliott Bay five blocks away.

I went to ask Nickels about the role cities can play in addressing climate change. And I went hoping to learn why he would be out of a job in a few weeks. That is, why this supposedly environment-minded city—the Emerald City—rejected a genuinely green politician, handing him an ignoble third-place primary finish in August that eliminated him before the general election.

The 54-year-old mayor was alert and distinctly relaxed in his office, perhaps because the burden of running a recession-addled city was about to be lifted from his shoulders. Or perhaps because he’s learned to work through the city’s gloomy seasons.

During the bleak Bush years, when the White House actively blocked international diplomacy on climate change, Nickels stepped up to craft the U.S. Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement. By joining, cities pledged to voluntarily reduce their global-warming pollution in line with the targets of the Kyoto Protocol. At the outset in early 2005, Nickels persuaded 132 cities to sign on, realizing that “if it was only Seattle, it would be purely symbolic. And it’s hard to get people to change their behavior for symbolic reasons.” To date, 1,017 U.S. cities have joined (though measuring their actual performance is another matter).

“When I became mayor in 2002, climate was not on my list of to-dos,” Nickels told me. “I filled some potholes and had to deal with the aftermath of 9/11–trying to put people back to work because we got hit harder than any other part of the country because we build airplanes here.”

Over the next few years he read reports on the shrinking snowpack in the Cascade Mountains—the source of Seattle’s water and hydroelectric power supply. This, he said, led him to make climate a priority. “I did it because our snowpack is as vulnerable to climate change as any feature anywhere,” he said. “I want to protect our water supply, and I want to protect our green energy supply.”

In late 2005, he traveled to the Montreal international climate talks to spread the message that U.S. cities were engaged on the climate issue. Simply showing “that there is intelligent life in America,” as he put it, seemed to relieve world leaders. (He’ll be in Copenhagen this month as well, speaking at the Climate Summit for Mayors.)

Seattle skyline. At home in Seattle, Nickels set out to make good on his international message with a $37 million Climate Action Plan. He focused on energy-efficient buildings, worked to remove a cap on downtown density, and supported zoning that encouraged compact “urban centers.” He added bike lanes and sidewalks and simplified curbside recycling and composting. On his watch, Seattle City Light completed an earlier pledge to become the first carbon-neutral large electric utility in the nation. In July, the city opened its first light-rail line, stage one of a broader rail plan that Nickels considers a signature achievement. When Barack Obama took office this year, with an urban perspective and a determination to bring the country back into international climate diplomacy, Nickels seemed poised to thrive.

Seattle skyline. At home in Seattle, Nickels set out to make good on his international message with a $37 million Climate Action Plan. He focused on energy-efficient buildings, worked to remove a cap on downtown density, and supported zoning that encouraged compact “urban centers.” He added bike lanes and sidewalks and simplified curbside recycling and composting. On his watch, Seattle City Light completed an earlier pledge to become the first carbon-neutral large electric utility in the nation. In July, the city opened its first light-rail line, stage one of a broader rail plan that Nickels considers a signature achievement. When Barack Obama took office this year, with an urban perspective and a determination to bring the country back into international climate diplomacy, Nickels seemed poised to thrive.

It all goes pear-shaped

So what went wrong? Nickels didn’t lose the election for any reasons related to this climate work, according to him and everybody else I asked about this. There was a botched response to a snowstorm last winter—city plows cleared the mayor’s neighborhood but few other streets in the city for several days. There was a perception that Nickels favored downtown interests over other neighborhoods, and that his leadership style was too aggressive for Seattle’s consensus-driven, feel-good political culture. (Characterizing him as a Richard M. Daley-style bully is a favorite local conceit.) Above all, there was his support for a $4.2 billion expressway tunnel (we’ll get to that later).

Nickels’ global leadership on climate change didn’t make up for that lost favor. In fact, the climate-hero reputation never really caught on at home. “I don’t think the election was a repudiation of [his climate-change work],” said K.C. Golden, policy director at the regional advocacy group Climate Solutions and an informal adviser to Nickels. “But it sure as hell wasn’t a recognition of it either.”

The political columnist Joel Connelly, who has covered Nickels since his county-council days, suggested the mayor ran into trouble because the environmental leanings of Northwesterners are tempered by an independent streak. He pointed to Nickels’ support for a 20-cent fee on disposable bags, a measure that voters emphatically rejected.

“I think our backs get up more than most at the bossiness of government,” Connelly said. “Nickels’ program became identified a little bit with the ‘nanny state.'”

To avoid overlooking the obvious, Nickels also faced a challenger with strong environmental credentials. Mike McGinn, a bicycling advocate and former chair of the Sierra Club’s Cascade Chapter, essentially ran to Nickels’ left, narrowly winning the primary and then narrowly winning the November general election.

There are other reasons Seattle voters didn’t buy Nickels’ climate-hero thing: up close, his policies to address climate change are not seen as especially bold. To take it further, Seattle isn’t seen as an especially green city among eco-minded policymakers and activists.

I talked this over with Seattleite Alex Steffen, executive editor of Worldchanging and a resolute Big Picture guy—of late he’s been proposing that Seattle become North America’s first carbon-neutral city. Steffen suggests that the solutions to climate change can be sorted as “energy supply” and “everything else.”

By luck of its geography, Seattle gets about 90 percent of its energy supply from low-carbon hydroelectric dams. “Everything else” includes the physical spaces people use (mostly buildings), how they move around (transportation), and the amount of moving they must do in their daily lives (planning and zoning).

In taking on these challenges in their separate careers, Steffen and Nickels each concluded that cities are where it’s at. The world’s cities, by many accounts, are responsible for 75 percent of all carbon dioxide emissions. They are also centers of innovation and creativity, and their governments can be more responsive than nations and international bodies.

Seattle trafficCourtesy Oran Viriyincy via Flickr.Seattle, local urbanist types will tell you, simply doesn’t rank among the world’s flagship cities on sustainable innovation—places like Vancouver, Portland, or Copenhagen. The chief reason is transportation. Seattle has a single light-rail line, a single monorail line connecting two tourist hubs, a bus network that runs on traffic-clogged streets (with some bus-only lanes), and terrible traffic problems.

Seattle trafficCourtesy Oran Viriyincy via Flickr.Seattle, local urbanist types will tell you, simply doesn’t rank among the world’s flagship cities on sustainable innovation—places like Vancouver, Portland, or Copenhagen. The chief reason is transportation. Seattle has a single light-rail line, a single monorail line connecting two tourist hubs, a bus network that runs on traffic-clogged streets (with some bus-only lanes), and terrible traffic problems.

“We are a dramatically auto-dependent region,” said Steffen. “We’re basically L.A. with rain, when it comes to cars.”

Nickels’ handling of transportation issues certainly contributed to his election loss. There’s a convoluted saga about Nickels supporting then opposing a new monorail expansion plan, which was never built. It wasn’t his fault, but it didn’t earn him a reputation as a public-transit visionary. And then there’s bicycle-friendliness (and general eco-coolness), where Seattle has a inferiority complex to its neighbor to the south, Portland. Nickels notes that his administration added bike lanes and paths and created a Bicycle Master Plan, but it’s tough to argue that made him a bike-infrastructure champion.

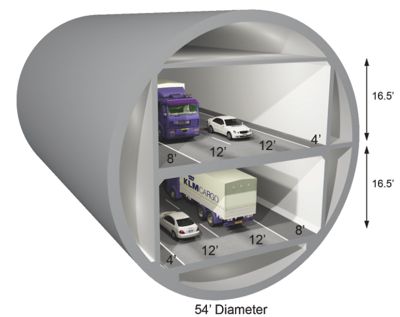

But more than anything, the downtown tunnel may have sealed his fate. The plan is for an auto-only behemoth, perhaps the largest such public infrastructure project in the country, with no room for public transit lines. It skimps on downtown exits, fueling criticism that it’s designed to shuttle suburbanites from one edge of the city to another. City taxpayers are responsible for cost overruns, and the perception is that urban representatives–who wanted a less costly street-level option–were outmuscled by suburban and rural interests in the statehouse.

Where do the trains go? Not in this tunnel.Nickels opposed the tunnel at first, then fought to get it reduced from six lanes to four. Eventually he supported it, noting that, even with new light-rail lines, “there still will be a need for the delivery truck and people to take trips that transit will just not quite be able to replace.”

Where do the trains go? Not in this tunnel.Nickels opposed the tunnel at first, then fought to get it reduced from six lanes to four. Eventually he supported it, noting that, even with new light-rail lines, “there still will be a need for the delivery truck and people to take trips that transit will just not quite be able to replace.”

Local environmentalists and urbanists, says Steffen, view the $4.2 billion investment in fossil-fuel transportation as “not just a bad decision, but a catastrophic decision.”

“Greg Nickels just didn’t get what a pickle we’re in here in Seattle,” he said. “When the tough decisions came down, the perception was that he wasn’t willing to spend the political capital to do the forward-looking thing.”

Looking ahead

The city could well pursue bolder plans in the near future. In January, when McGinn becomes mayor and Richard Conlin—cofounder of Sustainable Seattle—becomes city council president, Seattle will have environmental activists in its two most powerful political positions. A spokesman for McGinn didn’t say specifically whether he would stick to Nickels’ climate plan, though he said McGinn campaigned on making sustainable development a priority.

Nickels said he hasn’t decided about future plans—perhaps teaching, or NGO work with a national or international focus. “It will still involve cities and climate, energy, sustainability issues, I suspect,” he said.

He didn’t bite when I suggested the Obama administration needs a new green jobs czar, though he’s spoken with the White House personnel office.

Nickels was quick to talk up the climate work of other cities—Tulsa, Okla., has an office of sustainability; Austin, Texas, developed plug-in hybrid infrastructure; Carmel, Ind., uses roundabouts to reduce idling emissions, he said. He acknowledged that the voluntary climate plans hatched under the mayors’ agreement can become policy orphans, so to speak, when mayors leave office. Yet he argued that one of the key functions of city leadership is to show members of Congress that their constituents support climate action. The U.S. Conference of Mayors (Nickels is president, by the way) supports a national clean-energy bill, and Nickels figures that mayors can provide political cover for federal lawmakers to pass a bill.

“The climate debate that’s occurring in Congress is not the end,” he said. “It’s the beginning. [Cities] are going to have to take whatever Congress passes and make it real. That’s the hard work that’s going to take 20, 30, 40, 50 years. … There’s plenty of work to be done.”