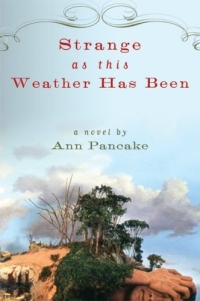

Editor’s Note: Author Ann Pancake grew up in the heart of West Virginia coal country. Her 2007 novel Strange as this Weather Has Been is the story of one family’s struggle against the relentless destruction of its beloved mountains.

I went home to West Virginia a couple weeks ago. October is the most beautiful season in Appalachia. The reds and russets, the yellows and oranges and purplebrowns, put into even more terrible relief the experience of swinging around a bend and seeing the horizon blasted to a dead gray mesa. October also means deer season’s coming soon, and in preparation, some people run the night roads with spotlights. It’s illegal to hunt by jacklighting, so most of these hunters are just scouting: sweeping the fields with their bright lights, freezing the deer, marking in their minds where the big bucks are so they can return some November dawn when the season is on.

Ann Pancake’s novel about mountaintop mining Appalachia lies in the East Coast’s shadow, there on the backside of urban centers like Washington, D.C., pushing up against them, but never touching. Appalachia generally stays dark (to most eyes) until the powers-that-be decide to turn around and throw the lights. One of these periodic flash-ons has happened just this fall, with the debut of the new film Coal Country and the release of a book of photos on mountaintop removal called Plundering Appalachia. The New York Times has run a series on the region’s contaminated water, and many media outlets are reporting on the rising acts of civil disobedience against mountaintop removal. Most significant of all, in September the Obama administration’s EPA announced they would actually review mountaintop removal permits to see if they violate the Clean Water Act instead of rubberstamping them as the Bush administration did.

Ann Pancake’s novel about mountaintop mining Appalachia lies in the East Coast’s shadow, there on the backside of urban centers like Washington, D.C., pushing up against them, but never touching. Appalachia generally stays dark (to most eyes) until the powers-that-be decide to turn around and throw the lights. One of these periodic flash-ons has happened just this fall, with the debut of the new film Coal Country and the release of a book of photos on mountaintop removal called Plundering Appalachia. The New York Times has run a series on the region’s contaminated water, and many media outlets are reporting on the rising acts of civil disobedience against mountaintop removal. Most significant of all, in September the Obama administration’s EPA announced they would actually review mountaintop removal permits to see if they violate the Clean Water Act instead of rubberstamping them as the Bush administration did.

Appalachia has always played the dark Other in the American imagination, and America has historically only looked at it when some perceived quality of the region serves the nation’s ideological needs. You can see this pattern at least as far back as the nativist movement at the turn of the twentieth century, when Appalachia was jacklighted as a reservoir of pure Anglo-Saxon blood. You see it in Appalachia as poster child of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. You see it in West Virginian Jessica Lynch cast as small town America Iraq War hero; in hillbilly Lynndie England as scapegoat for Abu Graib. Now, as the American public becomes more environmentally conscious, more aware of global warming and fossil fuel’s contribution to it, and as Obama gives some Americans “Hope” that we might actually be able to “Change,” America glances at Appalachia again.

In the meantime, in the hollows and along the creeks in the Appalachian coalfields, people continue to bathe their children in clean water trucked in to their churches because their own wells have been contaminated by coal slurry, to take down their pictures and knick knacks so they won’t be shattered by blasts, to power-wash the blasting dirt and coal dust from their houses, to stand vigil by flash-flood prone streams when it rains. Those residents who actually work on a mountaintop removal site-who hold one of the very few decent paying jobs in the region-have been riled to near hysteria by coal company propaganda shrieking about how the EPA is trying to shut down every coal mine — mountaintop, contour, and underground-in Appalachia.

Photo: Vivian Stockman Those of us who’ve actively opposed mountaintop removal for years meet the EPA’s announcement with guarded optimism or leavened cynicism. (The most recent headline on the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition’s newsletter reads: “Major News! EPA May Do Its Job.”) Before 2008 when George W. Bush suspended the part of the Clean Water Act that prohibited mining activity within 100 feet of a stream, mountaintop removal was illegal, without question. Even after the Bush change, its legality is a matter of intense debate with some judges ruling that mountaintop mining is legal, others ruling that it isn’t. Yet for years, we watched the permits approved anyway. We’re still bracing from just this past spring when the EPA also announced they’d review permits, then went ahead and okayed 42 out of 48 anyway, a bit of news that didn’t get much media light.

Photo: Vivian Stockman Those of us who’ve actively opposed mountaintop removal for years meet the EPA’s announcement with guarded optimism or leavened cynicism. (The most recent headline on the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition’s newsletter reads: “Major News! EPA May Do Its Job.”) Before 2008 when George W. Bush suspended the part of the Clean Water Act that prohibited mining activity within 100 feet of a stream, mountaintop removal was illegal, without question. Even after the Bush change, its legality is a matter of intense debate with some judges ruling that mountaintop mining is legal, others ruling that it isn’t. Yet for years, we watched the permits approved anyway. We’re still bracing from just this past spring when the EPA also announced they’d review permits, then went ahead and okayed 42 out of 48 anyway, a bit of news that didn’t get much media light.

Early in October, I received a letter from a friend in the coalfields, Pauline Canterberry, a 79-year-old retired Dollar General Store manager who became an activist after a coal processing plant began choking her small town with coal dust. I think Pauline’s words are representative of how many residents feel:

It looks like Obama is making a half-hearted attempt at checking out Mountain Top Removal Mining and its devastation while the evidence of it gets broader and broader, you can drive these highways now and look up and see more and more bare tops on these mountains, and for the life of me I can’t understand our leaders who can’t see the future devastation this is going to have … Rick drove me over by a place between Orgas and Cabin Creek where an entire valley was dammed up with toxic waste for a mine, old thick green yellow and white gook you knew was draining down into someone’s water. I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind, it’s no wonder the Cancer is ravaging our people here, yet they just allow more and more of it to accumulate.

If Americans are serious about “Change,” it might serve them well to train the light on Appalachia long enough to really understand the past and present there. Because Appalachia, especially coal country Appalachia, is not really America’s dark Other. Appalachia is America under an X-Ray. In Appalachia’s ineradicable poverty after 150 years of exploitation by natural resource companies and in the accompanying environmental catastrophe, one can see, completely naked, how the American “system” is flawed and unsustainable. And if Appalachia is America under an X-Ray, then mountaintop removal is the centerpiece of that X-Ray. A distillation. A bald apocalyptic vision of what has gone horribly wrong in our culture, but that is in most other contexts more hidden, more subtle. In the obliteration of the Appalachians, the oldest mountain range in the world, we see, concretely, unambiguously, the exposure of profit-making without accountability. Of corporate control over democracy. Of the energy war right here on our own soil, the fallout of our careless overconsumption.

When I think about this fall’s spotlight on Appalachia, I slide between that guarded optimism and leavened cynicism. What I do know, after fighting against and writing about mountaintop removal for a decade now, is that public awareness of the issue-and by proxy, Americans’ awareness of the true cost of their electricity — has been raised a hundred-fold. I see myriad national movements shouting against mountaintop removal and for renewable energies, when back in 2003 I sat in an anti-mountaintop removal organizing meeting in Charleston, W. Va., and was told that one of the most prominent environmental organizations in the nation had written off our fight as “unwinnable.” I see the coal industry’s propaganda campaign as proof that Big Coal is finally genuinely threatened by our opposition to it. And as I travel around the country and read from my novel and speak about mountaintop removal, what gives me the most optimism is not the intermittent media attention or the recent civil disobedience, brave as those acts are, or even the EPA’s announcement that it might enforce the law-it’s the vast number of people I meet in their late teens and twenties, both inside Appalachia and outside it, who are enthusiastically and wholeheartedly and doggedly committed to fighting for sustainable ways of living. To remaking this mess.

Photo: Vivian Stockman

Photo: Vivian Stockman

It was in the late 1990’s and the first years of this decade that mountaintop removal became entrenched, that companies and workers became addicted to it, under the deliberate neglect of the Clinton administration and the active collaboration of Bush. During those years, the media’s darkness was broken only by an occasional glimmer. Maybe things would have been different if Appalachia’d been jacklighted more consistently then. By conservative estimates, we’ve now lost 470 mountains and 1200 miles of streams. We’ll get none of those back.

I try to go home every October, and last year, I stayed with some friends in the coalfields. We were finishing lunch when one asked, “How long has it been since you’ve been up Seng Creek?” Though my friends didn’t know it, interviews I’d done with two families from that hollow in the summer of 2000 became the kernel of my novel. Yet I’d never visited the real Seng Creek again. “Well, we got to get you up there,” my friend said.

We got up there. At least as far as we could go. Because in the years I’d not seen Seng Creek, the upper part of the hollow had been washed out by a flash flood off a mountaintop removal mine, just as our interviewees had sworn was coming. After that, the company had swept in and torn down all the homes. The topography was now altered beyond recognition with fill dirt and giant culverts and nonnative grass, a sediment pond where the church had been. Bulldozers worked the steep slopes above our car. I asked where the people we’d interviewed had gone. My friend said the elderly woman had moved into Charleston with her daughter. The other family? Nobody knew.

“We better get on out of here.” My friend cocked her head towards the bulldozers. “You don’t know when that rock might come on down.”

As we backed out, I thought about where that place still was. In the memories of the people who’d lived there and in their photographs, in their blood and in their souls. And in my sadness, I also felt gratitude, that on that July day, those people and that land had shared with me enough of their light that a trace of the place survived in me, too.