Photo: SolarReserveAt Rocketdyne’s San Fernando Valley headquarters outside Los Angeles there’s a whiff of the right stuff — of crew-cut guys in short-sleeve white shirts and skinny black ties — in a vast room that holds the massive rocket engines that propelled John Glenn and the Apollo 11 crew into space.

Photo: SolarReserveAt Rocketdyne’s San Fernando Valley headquarters outside Los Angeles there’s a whiff of the right stuff — of crew-cut guys in short-sleeve white shirts and skinny black ties — in a vast room that holds the massive rocket engines that propelled John Glenn and the Apollo 11 crew into space.

In one corner of this corporate space museum stands something different, though. It’s a scale model of a solar power tower, technology Rocketdyne developed a couple of decades ago as a spinoff of its work for NASA.

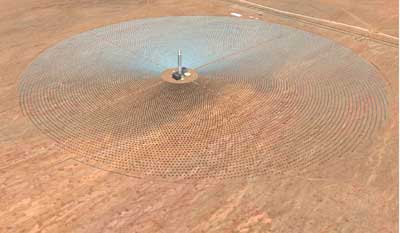

Here’s how it works: An array of mirrors called heliostats focuses sunlight on a receiver filled with molten salt; the stored heat can produce steam to run a solar power plant 24/7 — the elusive Holy Grail of solar energy. The technology, cast off as a non-commercial curiosity in the age of $18-a-barrel oil, is now being revived and could make Rocketdyne and its parent company, United Technologies, a big player in green tech.

A Santa Monica startup called SolarReserve — founded by, yes, rocket scientists from Rocketdyne — has licensed the solar power tower technology, turning the Silicon Valley model on its head: Take a proven yet obscure technology developed years ago by an old-line tech company and marry it to the entrepreneurial culture of a startup.

The company was in the news last week when it filed an application with California regulators to build a 150-megawatt solar power plant in the Sonoran Desert east of Palm Springs. The Rice Solar Energy Project will be able to store seven hours of the sun’s heat so it can be released when it’s cloudy or at night to create steam that drives an electricity-generating turbine. Future versions of the solar farm will be able to store up to 16 hours of solar energy. Other solar power companies are using energy storage but SolarReserve’s technology is a potential game-changer (more on that in a bit).

SolarReserve has kept a low-profile. Not surprising for a company founded by executives who previously needed government security clearances to get into their offices. (I only found out about the Rice project when I noticed SolarReserve had filed an application with the California Energy Commission.)

The company first caught my attention when a day after Lehman Brothers collapsed last September — setting off the global economic meltdown — the startup issued one of its rare press releases, announcing it had raised $140 million from a blue-chip roster of big players, including Citigroup and Credit Suisse.

A few weeks later I flew to Los Angeles to meet SolarReserve president Terry Murphy and his team, headquartered somewhat incongruously around the corner from Geffen Records, Lionsgate, and other outposts of the entertainment-industrial complex.

The SolarReserve execs were affable and eager to discuss their technology but close-mouthed about the dozens of deals they said were in the works for Big Solar power plants to be built in the desert Southwest and overseas. (One tantalizing hint they dropped was the interest of an unnamed utility in a massive complex of 10 SolarReserve power towers that would generate 1,000 megawatts.)

I’ve kept in touch with Murphy and even as the credit crunched worsened and the solar industry began to consolidate as startups ran out of money, he remained confident that SolarReserve would remain on track.

“We’re capable of riding this out,” Murphy told me a few months ago.

That’s because as investors run away from financing billion-dollar solar power plants using untried technology, SolarReserve’s ace in the hole is Rocketdyne and United Technologies.

The company that guaranteed Neil Armstrong made it to the moon will guarantee the performance of SolarReserve’s solar power plants. In these tough times, that’s what it takes to raise money on Wall Street or from well-capitalized utilities.

“SolarReserve has a very credit-worthy backer — United Technologies — which has said it will stand behind that technology and which gives them an edge,” said Tom Glascock, a global finance partner at the San Francisco law firm Orrick, at a recent seminar for green tech movers and shakers.

Rocketdyne’s molten salt technology was proven a decade ago at the 10-megawatt Solar Two demonstration project in the desert outside Barstow, Calif.

Solar Reserve’s planned Rice solar power plant will dwarf Solar Two. More than 17,000 heliostats — each mirror is 24 feet by 28 feet — will form a circle around a 538-foot-tall concrete tower. Atop the tower will sit a 100-foot receiver filled with 4.4 million gallons of liquefied salt.

When the sun rises each morning, the heliostats will focus their rays on the receiver, heating the salt to 1,050 degrees Fahrenheit. The hot salt will flow into a steam generation system that will drive a conventional turbine housed in a power block. After the sun sets, the salt will retain heat which can be used to generate electricity when demand spikes.

“The California utilities have peak demand from 1 p.m. until 8 p.m. so we are designed to run at 100 percent capacity during the full peak period into the evening,” Kevin Smith, SolarReserve’s chief executive, wrote in an e-mail message. “In addition, because of the storage capabilities, the facility is flexible enough to accommodate other requests from the utility after the sun goes down provided we understand the requests in advance.”

By being able to tap solar electricity on demand, utilities — at least those in the Southwest — could forgo spending billions of dollars on fossil fuel power plants that are fired up only a few times a year to prevent blackouts when everyone turns on their air conditioners on a hot day.

The Rice project is to be built on private land that is the site of a World War II-era Army airfield near the desert ghost town of Rice.

I happened to visit the site in late 2007 with an executive from Silicon Valley solar startup Ausra, which was shopping for land for solar power plants. Old artillery shell casings litter the desert scrub and you can still see the outlines of old runways. A massive concrete tarmac now serves as a parking spot for snowbirds’ RVs.

Ausra, an early player in the solar power plant business, has since dropped out, electing to focus on supplying solar thermal technology to developers rather than building its own projects.

With the Rice Solar Energy Project, SolarReserve is on the launch pad. Now it just needs to prove its salt.