This post was written by ProPublica’s Marcus Stern and Jake Bernstein.

To supporters, the “cash for clunkers” program miraculously jolted the moribund car market back to life, engendering hopes that it might help revive the broader U.S. economy.

To supporters, the “cash for clunkers” program miraculously jolted the moribund car market back to life, engendering hopes that it might help revive the broader U.S. economy.

Skeptics saw it differently: The automotive industry had hijacked an environmental bill and turned it into a bailout for itself with the help of the Obama administration and a Congress besotted with wishful thinking and a hair-trigger for stimulus spending.

Both views may turn out to be correct. But one thing is certain. The sight of car buyers back in showrooms these past two weeks has raised hopes that U.S. consumers are ready, primed by government stimulus, to spend again. Those hopes gained momentum by the release Friday (8/7) of employment data showing a reduced pace of job losses in the overall economy.

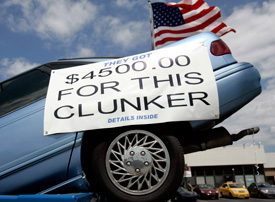

The idea, in concept, anyway, was simple: Bring in a clunker – a used car with lousy mileage – and collect up to $4,500 in government money against the purchase of a new car with a government-approved mileage level. The clunker, or more properly, its engine, is destroyed. Pollution and oil imports go down by at least some amount, not just this year but by many years into the future – because many of the clunkers otherwise would have remained on the road. And inventories of new cars are cleared from dealers’ lots, allowing dormant factories to restart. Some dealers are even saying that potential buyers whose used cars don’t turn out to qualify for the program are ending up taking a more normal trade-in and buying a new car anyway.

Questions, of course, remain. Having been broadly revamped at the behest of the powerful National Automobile Dealers Association (NADA), will the program deliver, along with economic stimulus, a meaningful increase in the fuel efficiency of America’s automotive fleet? How necessary was the $2 billion expansion of the original $1 billion program that Congress passed with stunning speed last week? And what about the increasingly frustrating paucity of believable, well-sourced data about the program?

“I am completely infuriated by the lack of information,” said Therese Langer, director of the transportation program at the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, a nonprofit research organization promoting energy security and environmental protection. “We asked for the transaction-by-transaction data, but (the Transportation Department) refused to give it.”

By knowing the mileage rating of the turned-in clunkers and the mileage rating of the new cars bought to replace them, analysts can get a better idea of the actual gas savings likely to be realized. The Transportation Department is releasing those numbers in summary form, but not the raw data that analysts like Langer seek.

“All of this information is being gathered and will be made public as soon as it’s available,” said Eric Bolton, a press officer for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), which is managing the clunkers program.

The problem, added NHTSA spokesman Rae Tyson, is that the rebate vouchers the agency had received as of last Friday contain personal information that must be redacted before the data can made public.

“It will happen, we just don’t know when,” Tyson said.

A brief timeline underscores the rapid pace of developments.

In January, Sens. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., and Susan Collins, R-Maine, joined by Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York, introduced a bill to fund a national program to stimulate the economy and get gas-guzzling vehicles off the roads. Similar programs had been successful in several states and countries.

The auto industry opposed the bill’s tight fuel-efficiency standards. But instead of simply resisting the measure, NADA, a key lobbying group, seized the idea and converted it to its own purposes. In June, the House approved an industry-backed bill with looser fuel-efficiency standards. A similar industry-backed bill was introduced in the Senate.

Under the Feinstein bill, consumers would receive $4,500 only if they purchased a passenger car with a fuel efficiency rating of at least 13 miles per gallon higher than the clunker they were dropping off. In the bill passed by the House, the rating difference was lowered to 10 miles per gallon or more.

That NADA could bring off this change is no surprise. Its enormous clout begins with its universality – there are car dealers in nearly every House district. The association made more than $7.5 million in campaign contributions to House members in the past six years and $773,000 to senators, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics. Separately, it spent almost $3.2 million on lobbying in 2008 alone, according to a database maintained by the U.S. Senate.

At first, the environmental proponents behind the original version were outraged. “The truth is, the House bill and its Senate counterpart are another big bailout,” Feinstein and Collins wrote in an opinion piece called “Handouts for Hummers,” published by the Wall Street Journal. “These bills are expertly designed to provide Detroit one last windfall in selling off gas guzzlers currently sitting on dealer lots because they’re not a smart buy.”

The bottom line, they argued, “is that fuel-efficient vehicles should be the main focus of any ‘cash for clunkers’ bill.”

But the competing legislation never went before the Senate for a vote. Instead, the industry-backed version was slipped into a completely unrelated war-spending bill that Congress approved on June 18.

Moreover, even Feinstein and Collins acquiesced after getting an oral commitment from Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., that the Senate would consider increasing the bill’s fuel efficiency standards if more money was needed for the program, according to Senate sources.

Thirteen days later, on July 1, the industry-backed version of the legislation became law with the formal name of the Car Allowance Rebate System, or CARS, and the weaker fuel efficiency standards. The $1 billion program was expected to provide rebates of up to $4,500 each for 250,000 auto sales.

For the next 24 days, the Department of Transportation hammered out the program’s rules as sales-starved dealers around the country began lining up deals.

The Transportation Department completed the rules and waved the green flag to start the program on July 24. Dealers across the country immediately began promoting the program and making deals.

Six days later, on July 30, trade publications reported that the money was running out. Unattributed reports said Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood would suspend the program at midnight for lack of funds.

The LaHood reports proved erroneous, but the media that evening began a brief shift in attention away from the health care debate to the delicious story of cash for clunkers, a government program that was so successful it had burned through $1 billion in stimulus funds within days.

The news reports were based on NADA’s spot survey of dealers, which estimated that 250,000 clunker sales already had been completed or were in the pipeline less than a week after the program began. Nobody, including the NADA and its dealers, was prepared for the popularity of the program.

Just 24 hours after the first press reports that the program was running out of money, the House hastily approved a $2 billion extension designed to underwrite 500,000 more sales. The money was taken from a renewable energy loan program.

Last Monday, after a briefing by the Transportation Department, Feinstein and Collins reversed themselves and agreed to support the $2 billion extension of the program, even with its lower industry-favored fuel-efficiency standards.

“The original intent of the clunkers program was to encourage people to buy more fuel-efficient vehicles, and the data so far tells us that’s exactly what’s happening,” Feinstein said. “So, I believe the right decision at this time is that the program should be extended.”

Environmental groups such as the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy also ended up backing the additional money for the program.

The Obama administration, waging a full-court press, clearly was gaining support for the costly extension of the rebate program through the week, despite some Republican opposition. On Thursday, the Senate approved the $2 billion extension. A week after the media frenzy about the program had erupted, the Senate forwarded the legislation to a president eager to sign it into law.

Calling it a “proven success,” President Obama responded to the news with a statement claiming that the program is “getting the oldest, dirtiest and most air polluting trucks and SUVs off the road for good,” and “businesses across the country—from small auto dealerships and suppliers to large auto manufacturers – are getting people back to work as a result of this program.”

Ultimately, the nation will have to wait months or even years to find out whether government got it right this time.

Has the program actually revived the traditional “animal spirits” among American car buyers, and jump-started an economy that needed a jolt, or has it simply borrowed sales that would have been made by this fall anyway? How truly clunky are the clunkers destroyed by the program, and how much better are the mileage ratings of their replacements. How much will gasoline use be reduced after a year, five years, 10 years?

Meanwhile, the nation’s new-car showrooms, for the first time in a long time, are buoyant and busy, despite some severe computer glitches during the first week of the program that delayed rebates and soured some dealers.

Sales employees at Shottenkirk Chevrolet in Quincy, Ill., appear pleased overall with the cash for clunkers program, even though it took them as long as 10 hours to log one deal on the government computer system at one point.

“Everyone is running out of cars,” Rich Poe, the dealership’s general manager, told the Quincy Herald-Whig. “Ultimately, the program has done what it was designed to do—sell more cars and get better gas-mileage cars on the road.”