After working for the United Steelworkers International Union for 30 years, Lauren Horne left in January to take on a new role within the labor movement — rallying union members to help fight climate change.

Union members call for a cleaner, greener economy.Photo: Step It UpHorne, a Pittsburgh native, is now coordinating an education campaign in Pennsylvania for the Labor Climate Project, a program run by the Blue Green Alliance. She spends her days traveling to union meetings throughout the state, where she teaches members about the problem of global warming and the ways that solutions could lead to new, green jobs for blue-collar workers.

Union members call for a cleaner, greener economy.Photo: Step It UpHorne, a Pittsburgh native, is now coordinating an education campaign in Pennsylvania for the Labor Climate Project, a program run by the Blue Green Alliance. She spends her days traveling to union meetings throughout the state, where she teaches members about the problem of global warming and the ways that solutions could lead to new, green jobs for blue-collar workers.

“One question I ask is, ‘Do we have any environmentalists in the room?’ And very, very few hands, if any, go up,” she said. “If they’re not familiar with [climate change], or if they don’t believe in it, I educate them.”

Ultimately, Horne ties her presentations back to the economy and jobs. “We talk about the economic situation today, which everyone knows about,” said Horne. “And then we also talk about the climate crisis situation, and about how by resolving one you can resolve the other and create good, family-sustaining jobs to help rebuild the middle class in this country again, particularly in manufacturing and construction, because those industries have been particularly hard-hit during this recession.”

Horne is now one of five veteran labor organizers working on the ground for the Labor Climate Project in Rust Belt states. Some 350 volunteers from the environmental and labor communities are doing similar education work for the campaign. Their goal is to create a network of union members who will be active in getting a climate and energy bill passed through Congress.

Blue Green Alliance Executive Director David FosterPhoto: Blue Green Alliance“I think generally people are surprised at how supportive union members tend to be on environmental issues,” said David Foster, executive director of the Blue Green Alliance (BGA). He was a district director for the Steelworkers until he left to help found the alliance in 2006. It started as a joint project of the Steelworkers and the Sierra Club, and has since expanded to include the Communications Workers of America, the Laborers’ International Union of North America, the Service Employees International Union, and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Blue Green Alliance Executive Director David FosterPhoto: Blue Green Alliance“I think generally people are surprised at how supportive union members tend to be on environmental issues,” said David Foster, executive director of the Blue Green Alliance (BGA). He was a district director for the Steelworkers until he left to help found the alliance in 2006. It started as a joint project of the Steelworkers and the Sierra Club, and has since expanded to include the Communications Workers of America, the Laborers’ International Union of North America, the Service Employees International Union, and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

But Foster notes that while union households are often sympathetic to green causes, there hasn’t been much outreach to them from the green community. BGA is now trying to remedy that by hiring organizers like Horne to help create “a blue-collar constituency for global warming solutions.”

“I’ve always believed that in organizing you’re better going to where people are at than standing outside and asking people to come to you,” said Foster.

Ramping up the pressure in D.C.

With the Obama administration gunning to get a climate bill passed this year, and the House already at work on one, the Blue Green Alliance has been increasing its presence in D.C. In March, the group hired its first full-time employee in the capital, Yvette Pena Lopes, who is serving as director of legislation and intergovernmental affairs. She comes from the Teamsters union, where she represented their 1.4 million members on trade, workers’ rights, and green-jobs issues.

“The challenge with the environmental movement has been that people have seen it as a choice between … taking care of their family financially, or doing what they think is right for the planet,” said Pena Lopes. “I think our job is to make both of those easy choices, and to not pit one against the other.”

Pena Lopes is working to ensure that the legislation coming out of Congress will not only address environment and energy concerns, but also boost employment opportunities. “It’s the No. 1 priority for environmental groups and also a very important priority for the labor groups in ensuring that these aren’t just environmentally focused policies that address climate change without taking into account the jobs aspect of it,” she said.

The Blue Green Alliance and a number of other labor organizations are encouraged so far by the Waxman-Markey climate and energy legislation that was passed by the House Energy and Commerce Committee on May 21. Foster called it “a positive step toward … a clean energy economy that provides good jobs in green manufacturing and skilled construction trades.”

AFL-CIO President John Sweeney praised the bill, saying that in its current form, “it makes significant, job-creating investments, while attempting to minimize impacts on existing workers.” The AFL-CIO — the largest federation of unions in the country — has become increasingly active in the environmental realm recently, in February unveiling plans for a new Center for Green Jobs in Washington, D.C.

The United Auto Workers also endorsed Waxman-Markey, happy that the bill includes funding to set up infrastructure for electric cars and retool auto plants to make advanced-technology vehicles. The United Mineworkers are on board too.

These labor groups like the basic framework of the Waxman-Markey bill — an economy-wide cap-and-trade program to curb greenhouse gases — but they have some differences of opinion over how quickly to reduce emissions. There is also disagreement over how to distribute pollution permits, with BGA wanting the permits auctioned off and the auction revenues used for public purposes, while the AFL-CIO wants permits given away to some energy-intensive industries. The current version of Waxman-Markey takes the latter approach, giving permits free of charge to industries like iron, steel, cement, and paper.

Still, overall, the bill in its current form is getting a hearty thumbs-up from the labor community.

That’s what friends are for

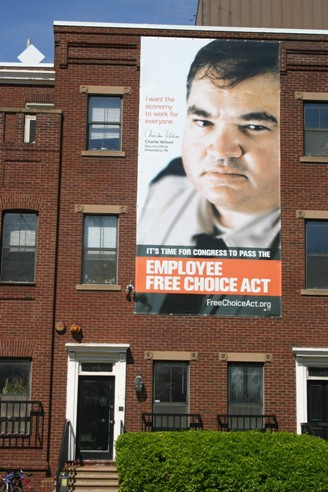

Employee Free Choice Act banner on Sierra Club building.Photo: Sierra ClubAs unions back the most important environmental legislation in years, some greens are now supporting the most important labor legislation in years: the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), which would make it easier for workers to unionize.

Employee Free Choice Act banner on Sierra Club building.Photo: Sierra ClubAs unions back the most important environmental legislation in years, some greens are now supporting the most important labor legislation in years: the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), which would make it easier for workers to unionize.

The Sierra Club has taken the lead on this front; it has formally backed EFCA since 2007, but has been more vocal in recent months. In April, the group rolled out a two-story banner on its Capitol Hill office featuring a giant image of a Philadelphia security worker with the words, “I want the economy to work for everyone.” The club has also hosted education sessions on the bill for staff, volunteers, and members, and sent out email action alerts asking supporters to call their members of Congress and encourage them to support EFCA.

“We’re looking at sustainability more broadly, not just reducing emissions but also a sustainable economy and sustainable conditions for workers,” explained Margrete Strand Ragnes, who splits her time between the Sierra Club, where she works on the Labor, Workers’ Rights & Trade Program, and the Blue Green Alliance, where she’s deputy director. “As we’re looking towards this new green energy economy that we believe has the potential to create millions of new jobs, we want to make sure those new green jobs are also good jobs. It’s not that all green jobs will be union jobs, but that workers should have the right to organize if they want to, so they can fight for better wages and benefits.” Strand Ragnes also argues that employees with union protections are more likely to report environmental concerns and health violations.

Of course, supporting EFCA is also a way to help strengthen the enviro-labor partnership by scratching labor’s back on an issue that’s exclusively theirs. Most issues the two movements have coordinated on in the past have been environmental, according to Brian Obach, a sociologist at SUNY New Paltz who studies social movement alliances. “For environmentalists to be taking a stand on Employee Free Choice is a significant breakthrough,” he said.

And while EFCA is outside the normal range of green issues, Foster of the Blue Green Alliance says it should be a natural fit. “I think environmentalists are generally very easy to persuade that if we reverse the trend of declining unionization in the United States, we increase the chances that we’ll have strong environmental protections in this country,” he said.

Labor groups outside of the BGA have praised the coalition’s environmental partners for stepping up on EFCA. “The work the Blue Green Alliance has done to build that understanding is very fundamental and very important,” said Bob Baugh, executive director of the Industrial Union Council and co-chair of the AFL-CIO’s Energy Task Force.

Past is prologue

The Blue Green Alliance has gotten a lot of attention for bridging two movements that have often been perceived as at odds with each other, but in fact environmental groups and unions have a long history of working together, even if they’ve butted heads at times.

In the late 1960s and the 1970s, the Steelworkers, United Auto Workers, and other unions joined with green groups to help pass the Clean Air and Clean Water acts, two landmark environmental bills of the 20th century, according to Scott Dewey, a legal scholar and environmental historian at UCLA.

In the 1980s, with the rise of Reaganomics and the drive for economic growth, relations between the two camps became more adversarial, said Obach, and environmental protection was portrayed as a job killer. “Historically employers have been very effective at using the jobs-versus-the-environment argument, that their interests are antithetical, and they’ve really been able to pit workers against environmentalists in many cases,” he explained. The two sides clashed over major environmental priorities, including fuel-economy standards for automobiles, drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve, logging, and endangered species.

Enviros and unions began partnering again in the 1990s on trade issues, when global trade agreements raised concerns about the loss of protections for both jobs and the environment. The 1999 World Trade Organization demonstrations in Seattle brought “turtles and Teamsters” together on the streets to protest sweeping trade deals being hashed out behind closed doors.

But the present-day confluence of an economic crisis and a climate crisis has helped bridge the two camps’ interests perhaps more than any issue in the past, according to Obach. Rather than just fighting against bad things, the two movements can now work toward a common, positive goal: a new, green economy.

“The whole idea of rebuilding the economy on the basis of sustainable industries has really opened up a lot more opportunity for unions and environmentalists to work together in a proactive way,” said Obach.

Of course, enviros and labor still have their differences on specific issues, and recognize that there are some areas where they may never agree. Unions tend to want more lax timetables for cutting greenhouse-gas emissions to limit economic disruption. Groups like the United Mine Workers and the Boilermakers Union want to ensure a sound future for the coal industry, while many environmentalists would like to see an end to all use of coal. The two movements have also disagreed over the trade protections they would like to see in climate bill.

Over the years, however, they have become more understanding of each other’s views on these issues, according to Baugh of the AFL-CIO. He credits the environmental community for an increased recognition of the importance of preserving jobs and economic growth. Baugh points to the example of the Kyoto Protocol, which unions did not back in 1997, largely because they were worried about international competitiveness since major developing nations like China and India were not included. Today, Baugh said, unions and enviros are largely agreed that there needs to be full international cooperation on a new climate treaty.

“I think the change for the environmental side is a far clearer recognition that jobs, economy, and employment are critical if we’re going to change our economy … It really matters about creating good jobs in a way that the environmental purists didn’t think or care about and they do now,” said Baugh. “You don’t want to trade off one for the other, and you don’t really have to.”

The Blue Green Alliance has worked to promote this sort of mutual understanding by bringing rank-and-file members of green groups and unions together at joint events like meet and greets, town halls, and political rallies.

“If this is only about polar bears drifting away on ice breaks, then we’re not going to make this an issue that’s relevant to the broader population,” said Strand Ragnes of BGA and the Sierra Club.

Bill they, or won’t they?

Both EFCA and a climate bill will be tough to pass through Congress. In March, it started looking like EFCA wouldn’t have the votes to pass in the Senate, though there’s now talk of a compromise. The House climate bill has jumped over its first hurdle, but has many still ahead, and climate legislation will be an even tougher sell in the Senate.

Unions and greens have some common foes on the bills. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce actively opposes both measures, and spent $15.5 million on lobbying in just the first quarter of 2009.

“We are going to educate the people in the center of the country as to the fact that they are the ones who are going to pay the tab and have to make the sacrifices” if a cap-and-trade bill passes, Chamber of Commerce Vice President William Kovacs told Politico recently. “The fight’s going to be in the center of the country.”

Whether or not they get a climate bill or EFCA passed this year, both labor and environmental leaders are optimistic about their prospects for long-term partnership.

Baugh believes relations between the two camps are now much stronger than they were in the past. “We lost for a long time, and this country couldn’t have a conversation about industrial policy,” he said. “It’s taken a long time to get back to this point, where we’ve got an economic crisis and a climate crisis, and in fact the answers are a cleaner planet and good jobs.”