Last year, Chris Hemsworth took a moment out of training for the sequel to his latest action film, Extraction, to promote the upcoming World Expo in Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates, or UAE. In a video featuring flying robots, levitating trains, and what appeared to be a terraformed Mars, the one-time “sexiest man alive” beckoned viewers to “the future.” Silver stallions galloped in the air as Hemsworth danced with a robot in a pink luminescent dress.

“This is Dubai,” his voice boomed. “And this is the world’s greatest show.”

The reality has been less fantastical. In October, opening day festivities at the Expo were marred by visitors fainting from temperatures above 100 degrees Fahrenheit. When I visited in late November, they still hovered around 90 degrees in the afternoon. The sugar cane and banana trees planted around the site looked parched, the leaves brown and droopy.

Though the heat may have come as a shock to the international tourists at the Expo, for me it felt familiar. Growing up in the Emirates, I was accustomed to 100-degree days. Summer months in the UAE were usually punctuated with news of construction worker deaths and videos of reporters and residents attempting to fry eggs on the sun-scorched pavement — and often succeeding. Still, after a few years in California’s Bay Area, I couldn’t help but be amazed that a place can be this hot in late autumn.

I had returned to my childhood home to visit family and explore the Dubai Expo. You’ll be forgiven if you haven’t heard of it. Commonly known as a world’s fair, the Expo is an international showcase that takes place once every five years, providing an opportunity for each country to promote its accomplishments and self-image. The Expo typically shows off technological innovations and architectural marvels: The Palace of Fine Arts near the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, for instance, is a remnant of the 1915 World Expo and was meant to prove to the world that the city had recovered from the 1906 earthquake.

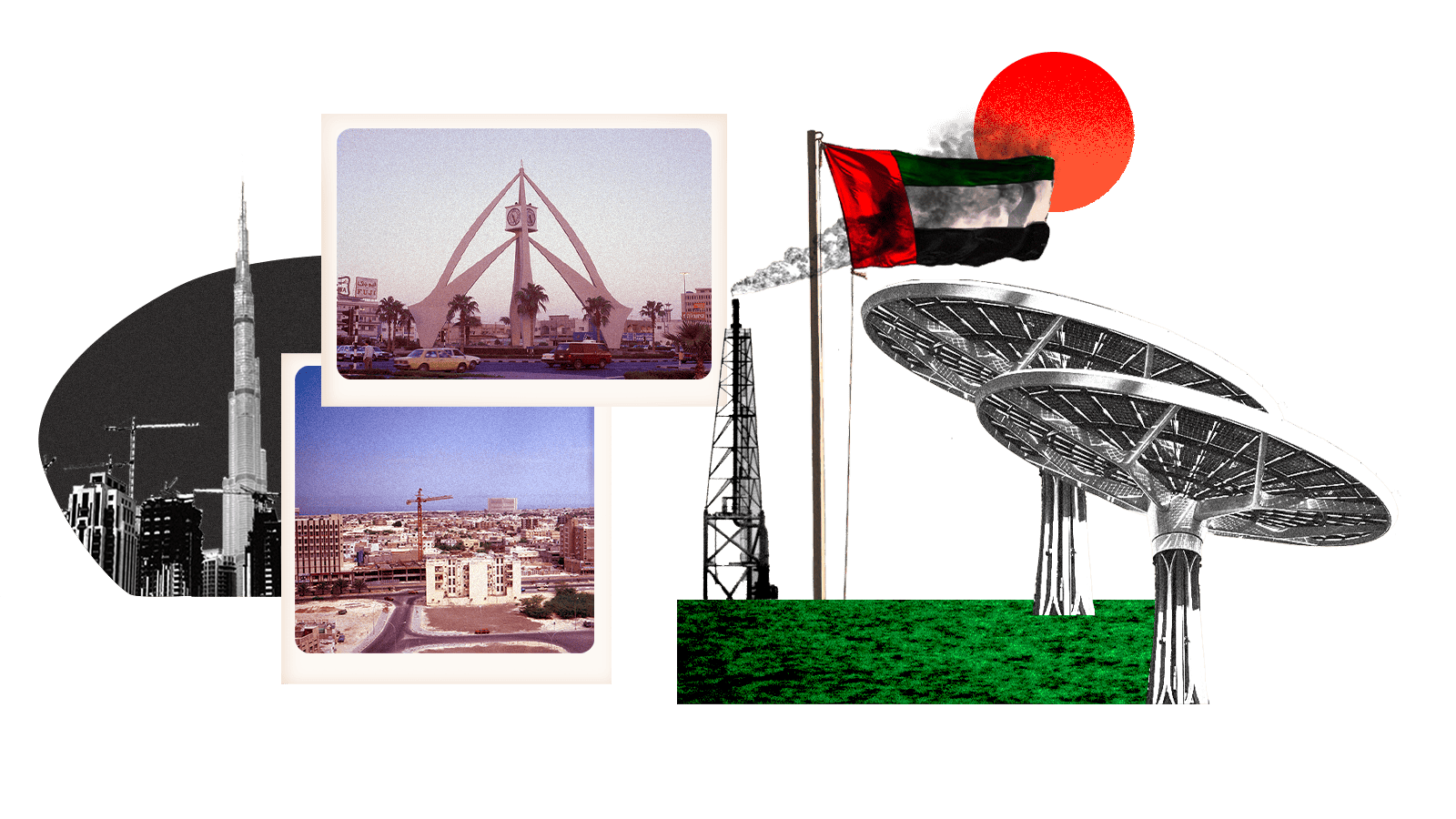

The Dubai Expo, which finally opened in October after a year of COVID-related delays and will run through the end of March, is built on a sprawling 1,083-acre site on the outskirts of the glistening metropolis. Each country has exhibits in one of three pavilions dedicated to the broad themes of mobility, opportunity, and, most curiously, sustainability. No expense appears to have been spared to prove the sustainability pavilion’s green bona fides. At its center sits Terra, a saucer-shaped building with solar panels on its roof. Along with 18 solar “energy trees” surrounding it, Terra produces enough energy to sustain itself and is expected to receive LEED Platinum certification. It also collects rainwater and dew that it recycles for use on site.

But as with the UAE itself, a different picture emerges when you scratch the Expo’s sleek surface. While Terra may be producing its own renewable energy, the Expo’s water is supplied by desalination, an energy-intensive process that removes salt from sea water and is primarily dependent on burning oil and gas. And while the Expo is powered by a solar park nearby, Dubai is still reliant on the Al Hassyan coal plant — the only such facility in the entire Middle East.

The UAE rose to global prominence over the last four decades on the strength of oil and gas reserves unearthed in the middle of the last century, and fossil fuels remain responsible for almost a third of the country’s gross domestic product. Though its oil production pales in comparison to larger neighboring rivals like Saudi Arabia, the small Gulf nation nevertheless accounts for about 6 percent of global petroleum exports. Oil funded the country’s rapid growth and famously lavish lifestyles. Today, its per capita carbon footprint is among the highest in the world — higher even than that of the U.S.

The country is nevertheless trying to position itself as a leader on climate action. In 2017, it announced a national climate change plan, and more recently it unveiled plans to produce half of all its energy needs from renewable sources. It aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 and just won a bid to host next year’s COP28, the United Nations conference that brings countries from around the world together to coordinate climate action.

Still, the UAE is not kicking fossil fuels anytime soon. Construction of the Al Hassyan power plant began just a few years ago, shortly after the country expanded its environment ministry’s mandate to tackle climate change and as it announced it would teach climate change in schools. In its energy strategy for 2050, the country expects “clean coal” will provide 12 percent of its energy needs. Another 50 percent will come from “clean energy” — presumably solar — and nuclear power. How the country plans to square emissions from coal and natural gas with its net-zero goal is unclear.

What’s more, the country’s net-zero goal ignores an enormous swath of its carbon ledger. In 2020, the UAE’s state-owned oil company announced the discovery of new oil reserves and efforts to increase oil production by almost 20 percent by 2030. A quirk in global carbon accounting rules mean that the petrostate may well cut carbon emissions domestically and reach its net-zero targets while continuing to expand oil and gas exports. Someone will burn those fuels — but as long as it’s not the country that pulled them out of the ground, it doesn’t count against the UAE’s ambitious targets. For this reason, the country’s climate strategy calls into question the meaningfulness of net-zero plans and exemplifies why some scientists oppose net-zero targets altogether.

Qais Al Suwaidi, the director of the climate change department at the UAE Ministry of Climate Change and Environment, said in a written statement that given the country’s significant cooling needs, renewables alone cannot meet the power demand. He said that “oil and gas will remain a part of the energy mix for a while” and that the UAE’s oil and gas sector has been “at the global forefront of adopting climate-friendly industry practices.” Al Suwaidi also referenced carbon capture efforts planned for the coal plant and a solar-powered hydrogen facility as examples of clean energy solutions.

“We believe that cleaner fossil fuels can play a vital role in the energy transition by capturing CO2 from large point sources, such as power plants, and storing it safely underground instead of releasing it into the atmosphere,” he said.

Ultimately, the UAE’s climate efforts may amount to nothing more than a creative way to extend the shelf life of its oil and gas assets. Every drop of oil that it conserves domestically — where energy is heavily subsidized — can be exported globally at market price.

“They don’t want to be left with a valueless asset in the future,” said Justin Dargin, a Middle East energy expert and a former Harvard University research fellow. “So they’re trying to produce as much as possible and export it before that nail in the coffin for oil consumption.”

The UAE is home for me — although it has never accepted me as one of its own. I’m one of the hundreds of thousands of people whose families immigrated to the country in the 1990s on work visas. After being overlooked for a promotion at the telecommunications company he worked for in southern India, my dad one day declared he was going to find a job in the Middle East. Within six months he moved to Saudi Arabia. When he found a job in Dubai a couple years later, my mom and I joined him. I was five at the time.

As a child, I didn’t understand the tradeoffs my parents made. For college-educated South Asians, the UAE offered career opportunities and economic mobility. It was safe and relatively socially progressive. Home was just a four-hour flight away, and to top things off: No taxes. In exchange, we lived with the uncertainty of being second-class in a country that wanted our labor but offered no safety net. We were on the lower rungs of a social hierarchy that valued native Emiratis and Western expats. We had no path to citizenship no matter how long we lived there. We lived with the knowledge that if the ruling sheikhs woke up one day and decided we were no longer useful to them, we would be on the next flight out. For this reason, my dad converted one of his old briefcases into a go-bag. Stored on a shelf above his neatly-ironed office wear, it held our passports and other important documents. I memorized the briefcase’s code when I was nine.

None of this struck me as odd growing up, though we spoke in hushed tones when we criticized the rulers because we’d heard a tenth of the population spied for the government. During the summers, we surmised that the government tampered with weather reports because the temperature never officially hit 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit), even though it sure felt like it.

It’s only as an adult, having moved out of the country, that I’ve been re-examining my childhood memories. We still don’t really know how many people spy for the government, but we do know that the country has used Israeli spyware to track dissidents and launched a messaging app that covertly spied on users. And while there’s absolutely no evidence the government altered weather reports, it was an easy rumor to believe considering the country’s notoriously harsh conditions for migrant workers doing manual labor. Given the rulers’ determination to build the tallest buildings, the largest malls, and man-made islands, it seemed impossible they’d let a little heat stand in their way, even though we’d heard local laws required outdoor work to halt above 50 degrees C. It was easier to imagine that the government would tweak weather reports instead.

Another reason these rumors seemed believable is that the country has always been obsessed with optics. It has carefully concocted an image that projects luxury, prosperity, and a sort of multicultural progressiveness. Dubai’s ruler has long been a fixture at the Royal Ascot, wearing a sharp top hat and hobnobbing with British royals. When the world’s airlines cut back amenities after the 2008 recession, Dubai’s airline, Emirates, doubled down with first-class cabins, in-flight showers, and lie-flat beds. Emirates continues to sign multi-million dollar deals with soccer clubs in the United Kingdom, a practice it began in the early 2000s. You can’t watch a soccer match any more without seeing a flash of Emirates’ logo on a jersey or on a sideline board on the field. The glitz obscures the harsh reality of life for many who built the country.

At the same time, it’s no exaggeration to say that the UAE — and Dubai in particular — has been a pioneer in the Middle East. When my family moved to Dubai, most hadn’t heard of the city, let alone could correctly point it out on a map. But three decades later, Dubai has become a tourist destination and trade hub, while the UAE is a powerful broker in Middle Eastern politics and a close ally of the United States. So much of its success is a credit to the country’s savvy rulers, who spent billions of dollars in profits from oil and gas exports to turn the dusty desert city into a gleaming metropolis. Its model of development has been inspirational to other Gulf countries.

When the UAE developed industrial zones for trade and manufacturing and poured billions into developing Dubai as a tourist destination, neighboring Gulf countries aped the strategy. After Dubai launched the Emirates airline, Bahrain, Qatar, and Oman followed suit. After Abu Dhabi signed deals with the Louvre and Guggenheim to build art museums in the city, Qatar, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia raced to build their own.

The UAE’s latest sustainability efforts may be both a recognition of its role as a regional leader and a public relations ploy to maintain its polished progressive image. It’s already working: After the UAE announced its net-zero target during COP26, Saudi Arabia announced a net-zero target of its own.

Ghiwa Nakat, the executive director of Greenpeace’s Middle East and North Africa office, said that it’s important to view the UAE’s climate efforts in the context of others in the region, where climate change has not been a priority. In this context, “we have to give [the UAE] credit,” she said.

“UAE has always had a pivotal leadership role in the region, and they are very good at challenging the status quo and driving positive change in the region,” said Nakat. “If anyone could drive this change within the region and achieve real zero [emissions], it’s UAE.”

Jim Krane, a longtime Associated Press correspondent who was posted in Dubai and is now a professor at Rice University in Houston, Texas, views the UAE’s attempts to stay ahead of the pack in business terms. “The UAE, and Dubai in particular, have always tried to get first-mover advantage,” he said.

True to its reputation as a country of superlatives, the largest solar park in the world is being built in Abu Dhabi, the Emirati capital. The UAE has also promised to invest $163 billion in renewable energy by 2050 and has committed to providing $400 million to a fund that helps accelerate the energy transition in developing countries. The fund is managed by the International Renewable Energy Agency, which is headquartered in Abu Dhabi.

The UAE’s investments — in green energy, aviation, tourism, trade, and expanding fossil fuel exports — seem almost perfectly calibrated to get the country to net-zero with as little sacrifice as possible. Like fossil fuel production for export, aviation and shipping emissions are not included in a country’s emission totals. Even emissions from Emirates, which is owned by the Dubai government and is the largest international airline in the world, are not added to the UAE’s carbon footprint. Similarly, shipping emissions from Dubai’s bustling ports are ignored.

The UAE has several other advantages: It imports 80 to 90 percent of the food it consumes, and its agricultural emissions are miniscule. Land is abundant, sunshine is plentiful, and an autocratic system of government means few bureaucratic hurdles and fewer concessions to public opinion.

“They’ve got a long way to go,” Krane summarized. “But it’s going to be an easier ride for them than it would be for many other countries.”

Even if it overshoots its goals, the UAE is poised to continue contributing to a warming planet. With no exit strategy for oil and gas production and the country’s coffers still heavily reliant on fossil fuels, Greenpeace’s Nakat warned that the UAE’s sustainability efforts could all be for naught. “They have to reduce their exports,” she said, “because even if it’s not burnt locally, the fossil fuel that is exported will have an impact on them.”

As the planet continues to warm, the UAE’s nearly 10 million residents will feel its effects acutely. The Middle East has been warming at a rate twice the global average, and the UAE is already 1.5 degrees C warmer than the preindustrial baseline. Researchers have found that if temperatures continue to rise, extreme heatwaves will make Dubai and Abu Dhabi uninhabitable by 2070.

Summers in the UAE have always been a challenge. Some of my earliest memories are tied to the relentless, draining heat: Sweating through my gray pinafore in elementary school, second showers after school, turning on the cold tap only to be blasted with scalding water. The sweet relief of stepping onto air-conditioned buses in fourth grade. Excitedly waiting for the winter months because it meant barbecues and picnics every weekend.

While the heat was mostly an inconvenience for me, it was deadly for others. At the height of its construction boom, the UAE depended on cheap labor mostly from South Asian countries. (Today, almost 90 percent of the UAE’s residents are expatriates, and half of all migrant workers are South Asian.) Many migrant laborers, particularly those who worked in the construction industry, were overworked, underpaid, and often found themselves trapped in a system of exploitation. With their passports seized by their employers, they were required to work long hours in the punishing heat, where many died of heat stroke. To this day, tallies of worker deaths and their causes are hard to come by.

The UAE is notoriously secretive about migrant worker deaths, blaming “natural causes” for the lives cut short. By one estimate, nearly 34,000 Indian migrant workers died in Gulf countries between 2014 and 2019. During the Expo construction alone, officials said three workers had died due to construction-related fatalities, but they declined to say how many had died offsite. The European Parliament asked countries to boycott the Expo in part due to the UAE’s “inhumane practices toward foreign workers” and “exposing them to extreme working hours in unsafe weather conditions.”

According to a report by the International Labor Organization, workers lose half of their work capacity as temperatures reach 93 degrees Fahrenheit. Temperatures routinely approach 120 degrees during summer months in the UAE. As the planet warms, the report projects that the UAE will lose the equivalent of 164,000 full-time jobs due to lost productivity by 2030 — the highest among Arab countries. And that’s not counting how many migrant workers may lose their lives.

Al Suwaidi, the UAE climate ministry official, said that the country is already taking steps to adapt to a changing climate. It has introduced a compulsory two and a half hour midday break for all outdoor workers during the summer months and a heat stress index is being used to gauge workplace safety. “It is necessary that we mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change, and build a climate-resilient future for the next generations,” he said. “Not taking action is not an option for us.”

The effects of climate change are also set to alter the UAE’s coastline. The country’s seven Emirates, including Dubai and Abu Dhabi, lie along the coast, and the cities have developed billions of dollars worth of waterfront properties. Dubai has also created entire man-made islands in the shape of palm trees and a map of the world. Luxury hotels, bungalows, and apartment buildings boasting sea-front views line the islands. As the seas rise, both the UAE’s coast and the islands are likely to be submerged. Under one extreme climate scenario, researchers predict that sea levels along the UAE’s coast will rise by 9 meters, flooding most of Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

It’s unclear whether Expo organizers considered climate projections in selecting its location. After the Expo winds down in March, the structures built for it are supposed to be repurposed into a “smart and sustainable city” called District 2020. If Dubai executes this plan, it may just put more people in harm’s way. Even a “mild” two-meter rise in sea levels will likely submerge the Expo site.

On the sticky November day I visited, no one appeared to be thinking about such dire futures. In the sustainability pavilion, people seemed thrilled to be outside and marvel at Dubai’s latest architectural wonders. Temperatures were dropping, winter was almost here, and with the Omicron variant still early in its spread, the mood was jubilant. As a group of men in kanduras tested their mizmars and drums, readying to sway to a traditional Emirati folk song, my tour guide leaned in with a bemused smile.

“I don’t know what they told you when you bought the tour,” he half-laughed. “Most people don’t want any sustainability knowledge. You tell them, ‘no water, no food’ — they don’t want that. They want some fun, some entertainment.”

Update: This article has been updated to include comment provided by UAE officials.