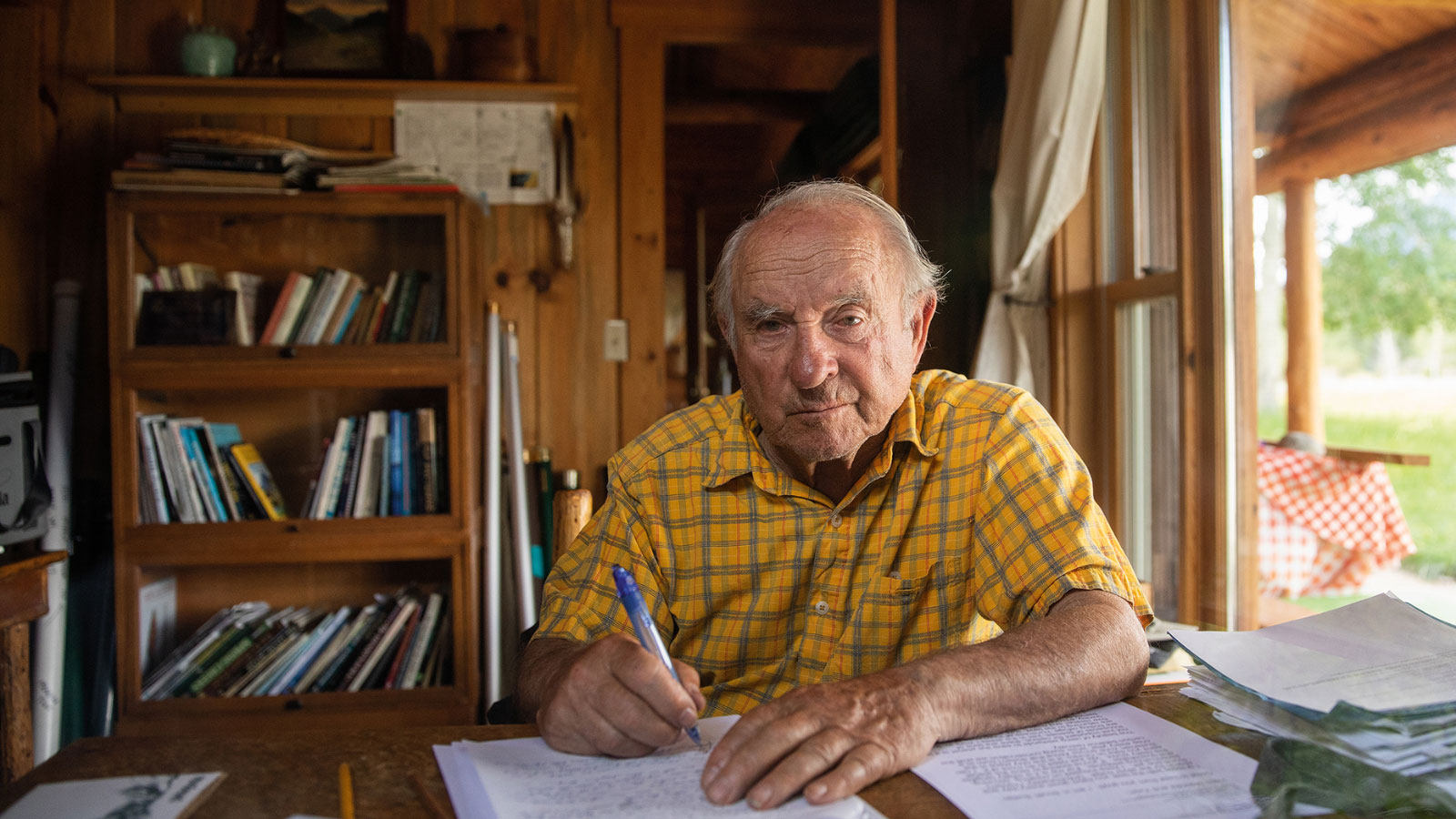

When Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard announced last week that he and family members were giving away the company to use its profits to fight climate change, the move was hailed as historic and remarkable by philanthropic experts.

The outdoor retailer, with a history of sustainability and environmental efforts, once told people to “think twice” before buying one of its iconic jackets. Now, in the wake of their decision to give away the company, some observers are in fact thinking twice — about whether the giveaway is actually that groundbreaking.

According to some legal experts, it’s a typical tax move.

Chouinard, his wife, and their two adult children transferred all of the company’s voting stock, or 2 percent of all shares, to the newly created Patagonia Purpose Trust, as first reported by the New York Times. The rest of the company’s stock has been transferred to a newly created social welfare organization, the Holdfast Collective, which will inject a projected $100 million a year into environmental nonprofits and political organizations. Patagonia Purpose Trust will oversee this mission and company operations. The giveaway was valued at roughly $3 billion and did not merit a charitable deduction, with the family paying $17.5 million in taxes on the donation to the trust.

While this move is groundbreaking in the philanthropic world, New York University law professor Daniel Hemel told Quartz that the giveaway allowed the family to reap the benefits of a commonly used tax law maneuver used by philanthropists. The Chouinard family paid more than $17 million in taxes when all was said and done, however, Hemel noted that the payment is a small percentage of the donation made, and the way the trusts and ruling organizations played out still allowed the family to call the shots on both the business and its future charitable contributions.

The Chouinard family’s gift has been compared to a recent move by conservative billionaire Barre Seid, who sold his entire company to the tune of $1.6 billion to fund right-wing political actions. When the New York Times reported on Seid, his transaction was noted to be shaded in dark money, while Patagonia’s was historic, despite both billionaires funneling money into 501c4 organizations. Hemel called out this juxtaposition both on Twitter and in his recent interview, where he said the gifts were “substantively similar.”

Billionaires use charitable giving to address a variety of issues, from right-wing politics to preserving wildlife. Communication and public policy professor Matthew Nisbet of Northeastern University has been outspoken against the role philanthropy and billionaires play in climate change before and told Grist that the newly announced Patagonia decision may be applauded by many in environmental industries, but Yvon Chouinard has essentially gone from a reluctant billionaire to political fat cat.

“Now that they’ve invented this (model) and introduced it to the marketplace for politically motivated billionaires, regardless of their background, everyone’s going to do it,“ Nisbet said. “This is an escalating zero-sum political arms race.” With the creation of the new 501c4 Holdfast Collective, Nisbet likened this new organization to other notable political spending groups, such as the National Rifle Association and the conservative Club for Growth.

A 501c4 organization, considered a tax-exempt, social welfare organization by the Internal Revenue Service, is not required to disclose its donors but must disclose money granted to other organizations equal to $5,000 or more. 501c4 organizations can engage in political lobbying and endorse candidates related to their organizational mission.*

Nisbet feared that the influx of cash controlled by an interest group would set the agenda of climate issues in the political realm moving forward. “Do you believe that our politics should be decided by billionaires who can spend hundreds of millions of dollars in elections with no accountability, no transparency, and pick and choose winners or pick and choose issues?” he asked.

Lack of transparency in political spending and philanthropy has mired public perception of charitable giving, causing long-standing scrutiny that dates back to 20th-century oil baron John D. Rockefeller’s creation of his namesake foundation. 501c4 organizations have funded anti-climate Facebook ads and directly influence climate legislation at the state level, with little knowledge of who funds these actions. While the source of the Holdfast Collective’s funding will come directly from Patagonia’s profits, Nisbet said he worries the new organization could become a way for other billionaires to donate and influence climate issues. Modern-day billionaires have taken climate change, the environment, and agriculture under their charitable wings more often in recent years, despite 10 percent of the world’s richest people producing half of the globe’s carbon emissions.

Soon-to-be trillionaire Jeff Bezos created a $10 billion Bezos Earth Fund in 2020, but Amazon has come under fire from watchdogs for undercounting its carbon footprint, punishing climate-focused workers, and polluting neighboring communities. Bill Gates has focused his philanthropy on agriculture and global hunger, while critics accuse him of gobbling up American farmland and cornering the market on seeds. Both Bezos and Gates have poured billions into tech-focused climate solutions, as well as Tesla founder Elon Musk also offering up $100 million for carbon capture innovations.

Patagonia has increased its political presence in recent years when it went to the courtroom to fight for the conservation of the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah and joined legal battles against logging, as well as commented on voting rights. The outdoor retail giant does have a long history of charitable giving, as they’ve donated 1 percent of all profits to environmental causes for decades and donated back $10 million of tax cuts to climate advocates.

Patagonia spokesperson Corley Kenna told Grist that, at this time, there are no publicly announced organizations that the company’s future funds will go to, but “all options are on the table.” She said Chouinard and the Holdfast Collective are interested in tackling the root causes of the climate crisis, including land and water protection, grantmaking to on-the-ground groups, and funding policy focused on solutions.

The spokesperson strongly rebuked the criticism that the recently announced company transition is not rooted in transparency and will fuel untraceable funds, citing Patagonia’s long history of transparency about its manufacturing, giving, and leadership.

“Yvon Chouinard, the Chouinard family, and the Holdfast Collective is not an extension of a political party,” Kenna said. “What we’re talking about here is a family that is committed to addressing the existential crises facing our planet.”

With big-name companies and wealthy families entering the fray, climate-focused philanthropy has grown in recent years, but still accounts for less than 2 percent of global giving, according to a report last year by ClimateWorks Foundation. Shawn Reifsteck, vice president of strategy and communications for the foundation, said Patagonia is “trailblazing a new way for companies to give back for generations to come” and he hopes others will follow suit. Philanthropic strategist Bruce DeBoskey said more and more philanthropists are recognizing that the traditional model of writing checks and giving grants has not been successful in solving overarching societal problems and billionaires are adopting new models of giving, such as the Chouinard family’s giveaway.

“It’s not about changes in the tax laws that I’m aware of,” DeBoskey said. “It’s about the changes in thinking.”

Editor’s note: Patagonia is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

*Correction: This story originally misidentified a 501c4 organization’s political capabilities.