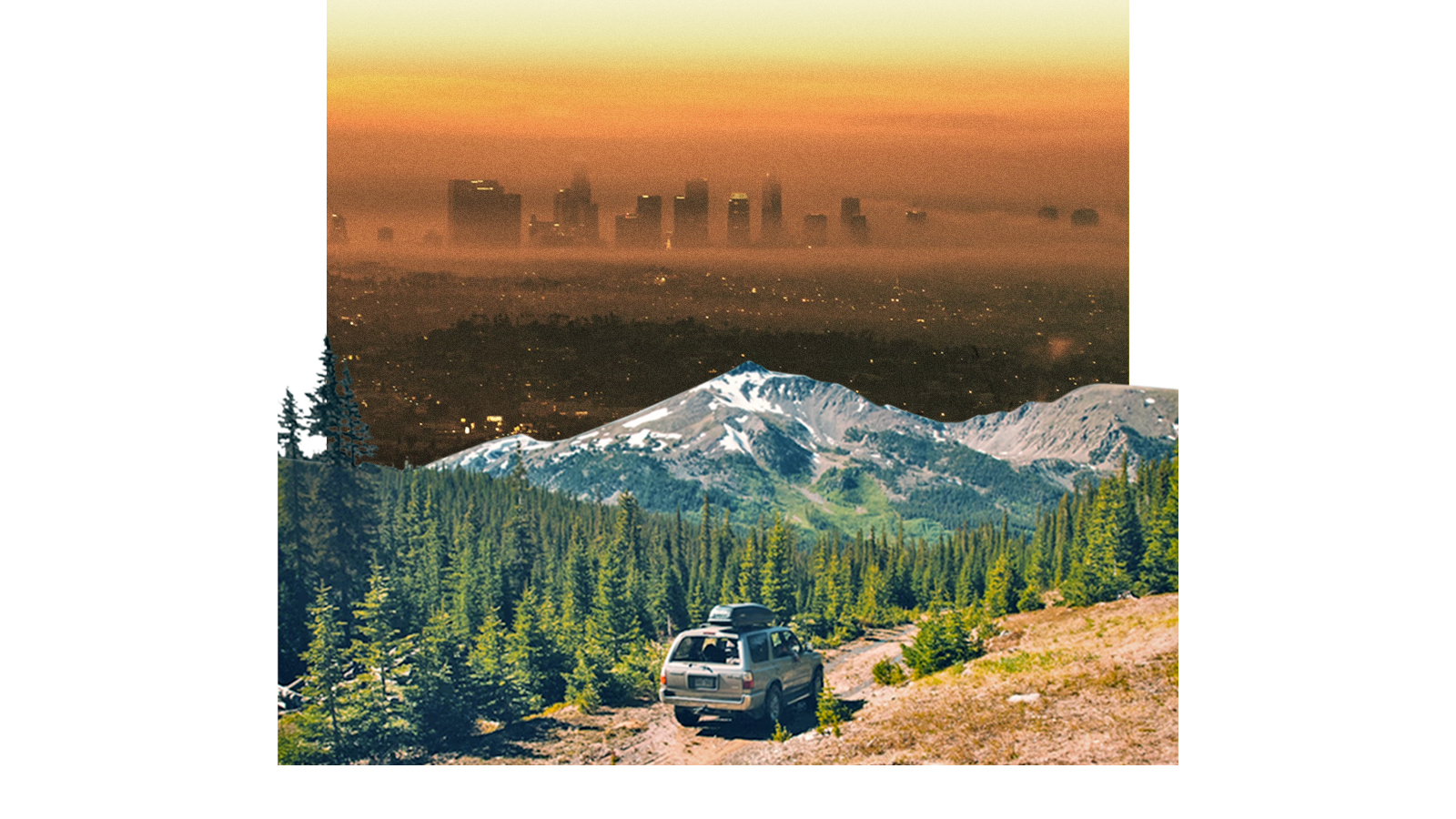

You’ve been seeing commercials like this all your life: An SUV steers off-road into a lush forest. An airplane soars over a pristine coastline. In fast-forward, a tiny green plant sprouts from the soil — something that appears to have nothing to do with the oil company behind the advertisement.

There’s a new word for this old marketing practice: “nature-rinsing.” It’s when polluting companies use images of charismatic animals, green plants, and wild landscapes to suggest that they’re more environmentally friendly than they actually are. Geoffrey Supran, a Harvard researcher who studies fossil fuel propaganda, coined the phrase in a recent working study that analyzed nearly 34,000 social media posts from polluting companies in Europe.

Nature-rinsing is nearly as ubiquitous as nature itself: According to the new report, written in collaboration with researchers at the nonprofit Algorithmic Transparency Institute at the National Conference on Citizenship, environment-related visuals made an appearance in 97 percent of posts from airlines this summer, and well over half of posts from automakers (64 percent) and oil companies (56 percent). “I was shocked by the scale of it when we actually started to quantify it,” Supran said.

The report highlights some striking examples. An Instagram post from the German airline Lufthansa shows an airplane with the bottom half replaced with a shark tail. The Irish Wizz Air put videos on Twitter that poked fun at airlines for using so many beautiful landscapes in their ads. “Look, a magnificent shoreline and soothing piano music,” the voiceover says as the camera slowly zooms in on green, coastal bluffs. “Showing you this doesn’t prove that we care about the planet.” (It’s the lack of business-class seating that shows they care, according to the ad.)

In recent years, activists have been calling more attention to this kind of deceptive marketing, known broadly as “greenwashing.” Research has found a large disconnect between the fossil fuel industry’s climate-conscious words and real-world actions. States, tribes, and advocacy groups have launched a wave of lawsuits against companies over greenwashing, alleging that it violates consumer protection rules by deceiving the public. A congressional committee has also been investigating oil companies’ misleading advertising.

In contrast, nature-rinsing is subtle enough, and so widespread, that it often goes unchallenged. Supran says that the practice has been overlooked by scholars, advocates, and policymakers. “Maybe this has been hiding in plain sight so effectively that we just take for granted the potential subconscious influences,” he said.

Marketing research has demonstrated the success of these tactics, finding that seeing nature-filled ads elicits pleasant feelings similar to seeing “real” nature. Several studies indicate that this emotional response misleads people and prompts them to view the advertiser’s brand more positively. Supran calls the practice of combining green-sounding marketing language with nature pictures “a powerful one-two punch.” Researchers have found that this double whammy of green messaging can even trick those knowledgeable about environmental problems into thinking companies are greener than they are. In the marketing field, nature-rinsing is known by the inscrutable term “executional greenwashing.”

Nature-rinsing has been around for decades, starting in an era when explicit, heavy-handed pitches were the norm. In the 1980s, Chevron made a series of commercials that looked like low-budget nature documentaries, eventually winning an Effie advertising award for the effort. In one, a grizzly bear awakens from hibernation to play in a grassy meadow where companies were supposedly drilling and exploring for oil mere months earlier. “Do people sometimes work all through the winter so nature can have spring all to herself?” a deep voice narrates. “People do.” In another, a fox pursued by a prowling coyote leaps to safety by clambering into an oil pipe — “a cozy den that keeps her snug and safe.”

The modern version is slightly more subtle as people have become savvier at spotting greenwashing. Take the “Nature or Nothing” campaign from Mercedes-Benz earlier this year, which promoted electric vehicles using close-up shots of a rose, a leaf, and honeycomb. A white circle was overlaid on areas where three lines converged to imitate the German carmaker’s logo. Some observers called it greenwashing, noting that Mercedes-Benz recently faced a lawsuit over its role in contributing to climate change. The advertisements inspired a parody campaign that superimposed the company’s logo over photos of spilled oil, wildfires, and cracking ice.

The recent report suggests that companies know what they’re doing. Posts that use green-sounding claims are statistically more likely to contain nature imagery, according to Supran’s report, which appears to be the first to demonstrate this correlation. “Fossil fuel interests are strategically appropriating the beauty of nature to strengthen their green language,” Supran said.

Companies that can’t convincingly spin their business as “green” may turn to nature imagery more often, Supran suggests. Oil companies can market their (usually tiny) investments in renewables and carmakers can showcase their new electric vehicles. By contrast, airlines’ talking points aren’t as solid: They’re still burning buttloads of jet fuel, with sustainable alternatives facing big hurdles. That might explain why nearly every aviation ad features the beauty of nature: They’re falling back on a safer greenwashing strategy that can easily fly under the radar.

Some countries have already taken steps to regulate the use of nature in advertisements. In France, courts have found that car companies have violated the country’s ethics code by advertising cars off-road in natural settings, a move that one judge declared “environmentally unfriendly behaviour.” Last month, France banned fossil-fuel ads altogether, and next year, it will force carmakers to promote biking, walking, public transport, or carpooling in all advertisements. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has recommended against using images of forests, the earth, or endangered animals if they might mislead people.

But most critiques of greenwashing have focused on language, which is both easier to quantify and easier to discredit. Nature-rinsing doesn’t make a specific statement — the images evoke a feel-good response, burnishing a brand’s reputation. And as research indicates, that emotional resonance is why it’s so persuasive.