It’s late October in the northeast corner of Wisconsin. Trees have started to change colors and a colder wind whips across Lake Michigan. Gas station marquees welcome back fall hunters on their annual pilgrimage.

Tucked away at a technical college, citizens of the rural town of Peshtigo, population 4,006, try to get comfortable in plastic chairs, ready to hear from state officials, once again, about ways they may one day safely drink their home’s well water.

Cindy Boyle, the town’s board chair, is there with her husband, Chuck, one row up from the back. Cindy recently took to the political arena after years of cooking and cleaning with just bottled water.

Across the room, Jeff Budish, an avid angler and outdoorsman, waits to speak. He’s footed thousands of dollars buying his own bottled water and water filters; he also just wants to be able to fish safely. A few rows up from him sits Doug Oitzinger, a founding member of a local clean water advocacy group, taking diligent notes.

If a clear solution was sought by those in attendance at the state’s most recent in-person Peshtigo PFAS meeting, residents walked away empty handed. Officials told residents that plans to provide new groundwater wells are coming from the company responsible for the pollution, but not everyone gets a well.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, or DNR, employees spoke at length about new data from water testing, but, without clear guidance from both the state and the federal government, and the mounting costs of providing alternative drinking water, officials’ hands are tied. Boyle, the town supervisor, said the DNR was doing everything in their limited power to help, but the company responsible is “uncooperative.”

Residents in Peshtigo are exposed to dangerously high levels of a group of toxins known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, in their groundwater, the source of their drinking water. PFAS are called “forever chemicals” because they are hard to break down in the environment. They’re also linked to high blood pressure in middle-aged women and stunted developmental growth in children, as well as kidney and testicular cancers.

Peshtigo’s PFAS problems stem from a local manufacturing facility that produces firefighting foam — a source of the chemicals so toxic that the Department of Defense recently banned their use. Over decades, a plume of PFAS spread through the community’s vast groundwater networks. Now, residents in this rural part of Wisconsin are forced to use bottled water to cook, clean, and drink until officials find ways to lower the chemicals’ concentrations.

The chemicals can be found everywhere: outdoor clothing, cosmetics, beef, rain, and even your blood. Cities from California to North Carolina have wrestled with contamination, with nearly every state having some form of pollution from these toxins and many now banning PFAS in all products sold within their borders.

At the start of this year alone, communities in Washington State, Massachusetts, and along the Mississippi River have reported elevated PFAS levels in groundwater and drinking water. The chemicals will take forever to break down in their environment, and if the rural town of Peshtigo is any indicator, the cleanup process will be just as long and arduous. Without enforceable standards from the federal level, states are scrambling to set their own standards and clean up procedures, a process that is often mired in politics.

“There was always a looming comment of ‘There’s something in the water.'”

Craig Koller, who grew up in Peshtigo, Wisconsin.

Peshtigo residents are torn over their options for getting clean water, which include the possibility of being absorbed into a nearby city and its public utilities, digging new wells at the expense of the company responsible, or building a brand new water utility system for Peshtigo itself. Hundreds of households are living on bottled water and water filtration systems. The town, state, and individuals have sued the company responsible.

Budish told Grist what he wants is simple: “What I’m looking for is clean water.”

But when PFAS are found in thousands of products, used in a variety of industries, and are now polluting every city in the country, determining who is responsible for the contamination and how it will be cleaned up gets messy.

In 2017, the state learned that Tyco, a subsidiary of global chemical conglomerate Johnson Controls International and one of the largest employers in the region, had been discharging PFAS into local streams and ditches in the region. According to state records, Tyco knew about these elevated levels at least four years earlier and failed to warn residents.

“This community has not been treated fairly,” Boyle told Grist.

The pollution stems from Tyco’s operations at a fire testing center that operated from the 1960s to 2017. This facility is located on the southern edge of the city of Marinette, roughly a mile from the town of Peshtigo.

First responders and military personnel would light planes, automobiles, and other heavy-duty equipment on fire at a location near the area high school, and then test the fire-suppressant foam Tyco sold. Afterward, gallons of foam would be washed away off the pavement into nearby streams where it would seep into the surrounding groundwater, eventually making its way into Peshtigo drinking wells.

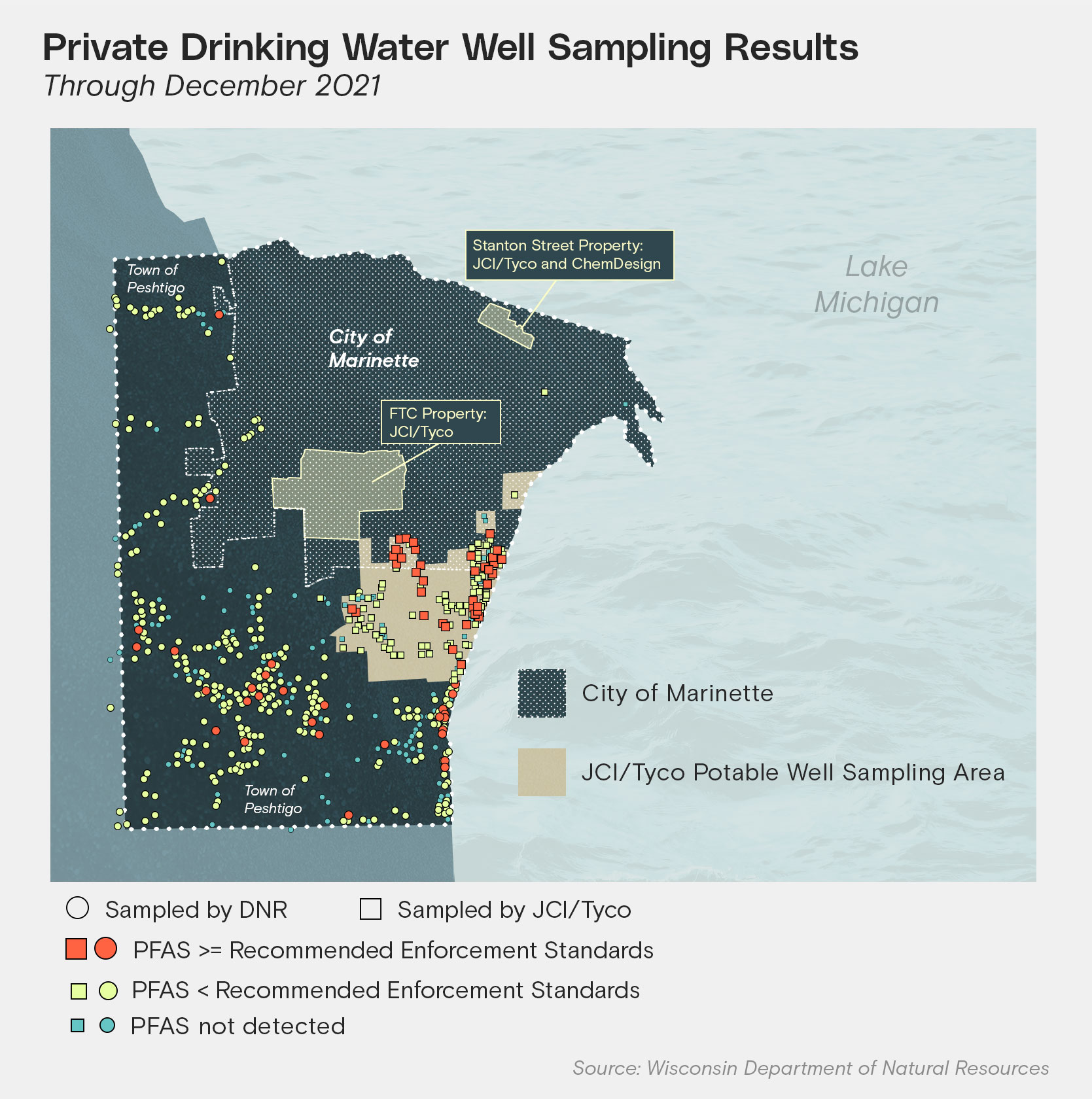

Tyco also has found elevated levels of the chemicals in groundwater near a Johnson Controls chemical production plant, known locally as the Stanton Street plant, in the city of Marinette on the Lake Michigan shore. With PFAS present, Marinette residents are cautioned against recreation and fishing in local waterways, but their drinking water is safer than their neighbors as Marinette draws its municipal water from Lake Michigan.

Founded in 1915 as Ansul Corporation, the company had been making fire suppression technology in the area since 1934. It eventually merged with the publicly traded Johnson Controls International in 2016.

Tyco still tests the firefighting foam at its facility in the region, but these tests are now done indoors, company officials told Grist, and all foam and water used are captured and disposed of properly. Johnson Controls International has been working on bringing a PFAS-free foam to market, but the product is not available yet.

But these new testing procedures don’t erase decades of PFAS pollution into area streams. Town of Peshtigo residents living near the testing facility have cited ongoing health problems, such as stomach cancers and developmental delays in children, that they believe to be linked to years of drinking PFAS-contaminated water. Craig Koller, who grew up drinking Peshtigo well water, was diagnosed with two forms of testicular cancer right after he graduated high school.

He said he’s seen classmates with the same cancer, and friends’ parents with stomach cancers and immunity disorders, all of which are linked to prolonged exposure to the chemicals.

“There was always a looming comment of ‘There’s something in the water’,’” Koller told Grist.

Since his initial diagnosis, he estimates he’s had hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of invasive treatments and surgeries, and is spending at least $1,200 a year on his weekly, post-surgical testosterone treatment. Koller, who now lives in the suburbs of Milwaukee, said the response from Tyco has been disingenuous and help at the local, state, and federal level has been disjointed.

“Normally FEMA [or the Federal Emergency Management Agency] would come in if a flood wiped out an entire community,” Koller said. “But this response is not conducive to helping people move on with their lives.”

The area has been severely impacted by PFAS contamination, with levels of the chemicals found reaching astronomical numbers over the state standards.

Concentrated, PFAS-filled foam, which looks like a pillowy, toxic cloud, has been found throughout the region’s waterways. DNR testing has found levels of the chemicals as high as 750,000 parts per trillion, or ppt, for the foam that sits on top of surface water.

Some of the area’s creeks have reported levels as high as 3,800 ppt. Groundwater wells closest to the facility have reported concentrations of roughly 2,100 ppt, or 30 times the state’s drinking water standards. Nearly 10 miles away from the fire testing facility, wells have tested positive for chemical levels over five times the state regulations.

Wisconsin recently established a drinking water standard of 70 ppt, which affects municipal water utilities. But this doesn’t change much for Peshtigo, or the other nearly third of the state that relies on groundwater for drinking. Groundwater standards are being reviewed again this year after political football struck them down last year.

The state created a grant program for replacing contaminated private wells last year, including those impacted by PFAS, and Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers, a Democrat, recently announced a 2023 budget proposal that would invest $100 million in PFAS cleanup across the state. This budget, however, has to make it through the state’s Republican majority.

At the federal level, the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, has found that basically no consumption of these chemicals is safe. The agency is in the midst of a review of its practices and regulations of drinking water standards for the chemicals. Currently, there is no national standard for PFAS in drinking water.

Peshtigo residents have urged federal officials to declare the fire testing facility and the Stanton Street plant as a Superfund site, which would allow the EPA to clean up the site on Tyco’s dime. The agency said it is still reviewing the petition, which noted that the sites are a threat to human health and the environment after half a century of firefighting foam testing went unregulated. The EPA told Grist that it expects to respond to the petition by March of this year.

To Liz Hitchcock, director of federal policy for Toxic-Free Future, a national consumer safety nonprofit that studies and advocates for PFAS cleanup in various industries, the federal government isn’t moving quickly enough. Most federal responses, she noted, have been prompted by a bubbling up of state-level action.

“This is not a problem that’s happening in isolation,” Hitchcock told Grist. “It’s happening all over the country because PFAS chemicals have been in use for years without adequate regulation.”

Because of the ubiquitous use of these chemicals, the federal response has varied by different agencies, from the military to the Food and Drug Administration.

“There are so many uses of PFAS,” Hitchcock said. “It’s not just an issue of cleaning it up, but preventing the problem in the first place.”

Johnson Controls acknowledges its role in the contamination and has pledged to fix the problem for the area’s most impacted residents.

Katie McGinty is Johnson Controls International’s Chief Sustainability Officer and a former environmental advisor to the Clinton administration.

“Tyco takes full responsibility for the impact of the water of these 169 neighbors from our historic activities,” she said.

This 169 number, however, is controversial.

According to McGinty, Tyco currently provides water filtration systems and bottled water for those homes because they fall within what is known as the “potable well sampling area,” or PWSA: a sliver of the town that both the company and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, or DNR, agree that Tyco polluted. The company has also constructed a $25 million Groundwater Extraction & Treatment System to remove the chemicals from the groundwater surrounding the fire testing facility. Outside of that, the two can’t agree on much.

Since the public announcement of the contamination, the DNR has conducted tests to study the spread of the contamination throughout the area’s groundwater systems. Forever chemicals have been found at elevated levels outside of the area Tyco takes responsibility for, a region known as the “expanded site area.”

Tyco is required to complete a site investigation to define the degree and extent of contamination related to its discharges of PFAS. In a statement, the DNR said results from Tyco’s completed site investigation, which the agency monitors, will be used to determine the company’s responsibility. Results are expected to be released this spring.

McGinty denies the company’s responsibility for these additional properties, arguing that the widespread prevalence of PFAS from various industries and consumer behaviors could have also played a role in contaminating groundwater in these expanded sites.

“We hope that the DNR will take action to determine and stop the sources of PFAS in that area, but Tyco is not the source,” McGinty said.

Last year, the Wisconsin Department of Justice filed an environmental enforcement lawsuit against the company for alleged failure to adhere to the state’s hazardous spill laws.

“It’s not just an issue of cleaning it up, but preventing the problem in the first place.”

– Liz Hitchcock, director of federal policy, Toxic-Free Future

As the back and forth of enforcement and corporate finger-pointing unfurls in legal battles and slow testing, residents that live outside the agreed-upon contamination area are on their own.

Budish, the angler from the Peshtigo town meeting, has lived at his property for 30 years, just off a state highway tucked behind rows of thick pine trees that stretch for miles, where neighbors get around using four-wheelers.

He lives outside of Tyco’s recognized area, but his drinking water is contaminated. He’s paid for private testing on his property and found high PFAS levels in his private well water, nearly 10 miles from the fire facility and even farther from the other plant, prompting him and his wife to buy their own bottled water for cooking and consumption for the past five years.

Speaking at the October meeting, he said he wonders if the ponds, creeks, and ditches surrounding his property on the outskirts of Peshtigo are also contaminated, but so far, he’s only been able to afford to test his groundwater drinking well.

He told Grist he estimates that he’s spent at least $100 a month on bottled water for the past five years. He has also purchased a water filtration system, which can range between $1,000 and $3,000.

Budish, wearing a camo hat and a blue sweater noting his love of fishing, lives in a state and region plagued by “don’t eat” advisories for both fish and deer, due to PFAS contamination.

“Why should I have to take everything out of my own pocket?” he asked.

Tyco is standing firm that its operations have not had anything to do with the contamination that residents like Budish face. The chemical signature of the PFAS found in the potable well sample area, the region it takes responsibility for, is vastly different from the ones found in the DNR’s expanded area, McGinty told Grist.

“If anybody in that expanded area is using dental floss, they’re putting some PFAS down their drain every day,” McGinty said. “If they’re doing some laundry, they’re putting PFAS down their drain. If they’re washing their frying pan, they’re putting some PFAS down their drain.”

Independent researchers from the University of Wisconsin, however, released research in January that tied Tyco’s chemical signature, or “PFAS fingerprint,” to a growing plume of chemicals in Green Bay, a freshwater bay of Lake Michigan located two miles from Stanton Street. Tyco said it has plans to review the study.

For the contamination it does claim responsibility for, Tyco will pay for new deep wells and water quality monitoring for residents. The wells will be drilled 500 feet into the ground and draw water from the deep aquifer in the area; Tyco will cover all expenses for 20 years. In addition, the company is paying out a $17.5 million class-action lawsuit, but only to those inside of the agreed-upon contaminated area.

Wisconsin environmental officials have been skeptical of Tyco’s deep well plans and have urged the company to not advertise new wells as a final, long-term solution. In a statement provided to Grist, the DNR said it agrees with the company’s design criteria for the deep wells, but concern for other contaminants, such as radium, strontium, and high iron, exist in the region.

As other states take aim at PFAS polluters, Governor Evers and state Attorney General Josh Kaul joined more than a dozen other states in suing large companies for their role in the contamination. The two Wisconsin officials filed a lawsuit last July against Tyco, 3M, DuPont, and other PFAS polluters in the state, alleging they should have known that the ordinary and intended use of their products would lead to dangerous impacts on public health and the environment across Wisconsin.

As company officials, regulators, and residents continue to fight over who is responsible for this growing crisis, costs are mounting. Since Tyco only claims responsibility for a sliver of the plume, the state is tasked with providing bottled water for residents outside the PWSA while the chemical company and the DNR hash out responsibilities in court. State testing and bottled water funds, however, are running out.

Christine Sieger, director of the agency’s remediation program, said just over half a million dollars has been spent by the DNR to provide bottled water to residents in the state, with the majority of those funds going to Peshtigo and French Island, Wisconsin, a community with newly discovered PFAS contamination. She told Grist that the agency has not been provided new or additional money from the legislature to supply bottled water to residents with PFAS-contaminated drinking water.

At the beginning of 2022, the DNR had tested over 400 wells in the extended area. Over 300 had PFAS detected in them. But funding ran out to conduct any more.

Melissa Agard, a Democratic Wisconsin state senator and lead author of a comprehensive bill to address PFAS and other pollutants, said the lack of appropriate funding for the DNR is part of a larger problem in the state — her colleagues across the aisle.

“The biggest roadblock we have is the majority party,” Agard, who represents the capital city Madison, a community also polluted with PFAS, and surrounding cities, told Grist.

Currently, Wisconsin has a Republican majority in both houses of the state legislature. Agard said she has attempted to introduce the bill multiple times in past years, but it has not seen the light of day through public hearing sessions, a process set by the majority party.

Republican members of the state’s finance committee have expressed interest in using the state’s historic surplus funding to address the problem, while a newly appointed DNR secretary has called for increased oversight and funding from the state legislature.

Agard said a lack of funding for bottled water is concerning, but bottled water is not a long-term solution.

“We are not taking a comprehensive, holistic approach to address PFAS contamination in the state of Wisconsin right now,” Agard said.

The Peshtigo town board is investigating the idea of creating a water utility district and paying for the utility by way of a lawsuit lodged by the rural town against the company last year. This costly infrastructure project recently secured $1.6 million of federal funds as part of a variety of PFAS remediation funds earmarked by Wisconsin Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin.

Still, not everyone in the town wants the increased taxes that potentially come with a public water supply, again highlighting the fractured nature of the area’s response to this national problem.

Jennifer Friday, a Peshtigo resident who lives in the PWSA, is pursuing yet another approach.

She doesn’t want the water utility district and has been involved with efforts to annex select households into Marinette, their bigger neighbor to the north. If this process moves forward, these residents would become citizens of Marinette and receive the city’s municipal water. Friday, who is now running against Boyle for the town chairperson seat, said she estimates 90 residents are interested in this process, but the group still needs a vote before Marinette’s city council.

If these residents annex themselves into the neighboring city, they would forgo their private wells for water from Lake Michigan’s Green Bay. As more and more communities around the Midwest are experiencing problems with their groundwater, be it contamination, aging infrastructure, or drying aquifers, Lake Michigan water is an increasingly hot commodity.

But that doesn’t mean it’s safe. While Green Bay has had low levels of the chemicals present in its waters in the past, concerns now linger after the University of Wisconsin study was released.

Tyco said it would provide neighbors in Peshtigo with the legal support they need to meet the requirements of the annexation process as well as offer to pay for the new costs associated with annexation, which include 20 years of increased property taxes and water bills for the annexed property. The annexation process has to be resident-driven and the city of Marinette must receive a petition from interested parties and vote on the annexation.

“I’m not pushing annexation,” Friday said. “I’m pushing resident choice.”

Andrea Maxwell, a Peshtigo resident for 10 years who has been provided water by Tyco for the last several, chose the deep well route instead, with the new system installed in early December. Her home is right in the center of the plume. While her well has not tested positive for PFAS, her neighbors’ have.

According to the company, more than 40 deep-well agreements have been signed; contractors are waiting for the ground to thaw to begin construction in the spring. Tyco will pay for the well maintenance, filters, water salt, testing, and other associated costs, including fixing any future PFAS contaminations.

“That’s a pretty good deal, we feel like,” Maxwell said, “rather than us sitting around worrying if we could maybe be contaminated in five years.”

Standing on Kayla Furton’s lawn in Peshtigo, you can see Green Bay. Around the corner, there’s a ditch with chemical hazard signs warning not to touch or consume the water in it.

Two houses down, no obvious geographical barriers exist, but her neighbors are outside of the zone Tyco claims responsibility for and have to fend for themselves to get clean water, much like Budish.

“It’s just an arbitrary line,” Furton, a town supervisor, told Grist.

To her, the fragmented, neighbor-versus-neighbor response has been hard on the community. She does qualify for a free well, but in doing so, she waives her liability rights. She also doesn’t see new deep wells for a small group of people as a permanent answer for the thousands of residents in the region.

“I do think people are tired,” she said. “I know I am. I know my kids are sick of hearing about PFAS.”

When asked if she has considered moving out of the area, Furton, who recently filed a lawsuit against Tyco, said she gets that question a lot, and it can be loaded. She believes her home is more than just a property; it’s where she grew up and where her children have planted roots.

“Yes, we could,” Furton said. “We could, but there’s no guarantee there’s not PFAS contamination somewhere else.”